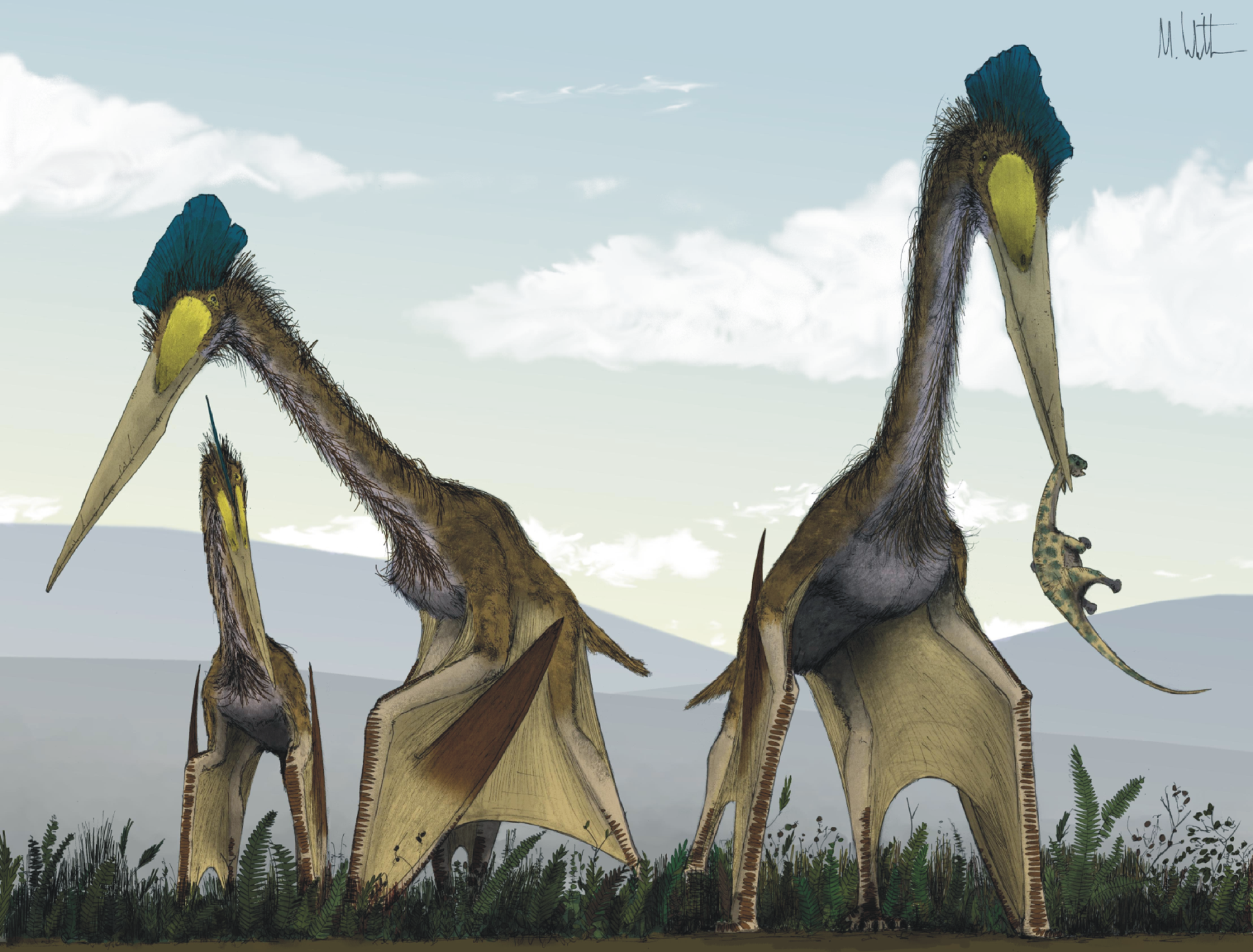

female – with wing tag

As someone who regularly requires the use of wild birds in my research, I often worry that the methods of capture and subsequent identification I use might in some way impede the individuals I capture upon release. I use wild blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) which I identify by means of a metal ring in conjunction with a unique combination of colour rings. Ringing has been used as a method of bird identification since 1909 when the first bird, a Lapwing ( Vanellus vanellus), was ringed in Aberdeen. Since then ringing has become one of the safest and most commonly used method of identification of wild-caught birds and as such has been an invaluable tool for the study of bird populations. One only has to look at some of the data collected by ringers on the age of some birds to be astounded by how long some individuals survive, information which would be extremely difficult to come by without the use of rings.

More recently however, other methods of identification have become increasingly popular, which are used in conjunction with ringing. Perhaps one of the most well known would be the use of wing tags, which are currently in use with the reintroduced Red Kite (Milvus milvus) here in Ireland, which I might add has been a huge success thus far. Yet data published in a recent study by Trefry et al. 2013 suggests that for some species the use of wing tags can be detrimental. Trefry et al. Studied the magnificent frigatebird (Fregata magnificens), a spectacular sea bird which is unusual in many ways not least for the fact that as a species that forages at sea they make every effort never to land on the surface of the water. In this study the researchers compared the effects of various methods of identification and measurement taking on the reproductive success of the birds. What they found was quite alarming, individuals which were simply ringed fared no different to individuals which were untouched by the researchers, but those which had wing tags added reared significantly fewer chicks to fledging. The reasons for this are as yet unclear, perhaps the addition of the tags impairs the aerodynamics of the wings to such an extent that tagged adults are less proficient foragers and therefore unable to meet the nutritional demands of their young.

There are more examples cited in the study by Trefry et al. which highlight the negative effect of such tags on other species of bird (as well as those on which they have no effect), which makes it clear that more research is needed in this area, to my knowledge no such study (and correct me if I’m wrong) has been carried out for our reintroduced red kites so one would hope that they are not doomed to fail before they begin.

Author

Keith McMahon: mcmahok[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit

wikimedia commons