Splitting the atom, unlocking the secrets of radiation, or even leading a peaceful civil rights movement.

I grew up knowing that these were the sorts of achievements that earn you a gold medal and an invitation to Sweden in mid-December. I have since learned that the annual ceremony held in honour of Alfred Nobel hasn’t always been awarded to the most deserving candidate, and that sometimes the winners simply stumbled upon a discovery that changed the world. This was not the case with the 2015 Nobel prize for Physiology and Medicine.

Scientists rarely aim for such high levels recognition, as it often comes decades after the initial discovery. Working in Natural Sciences is often considered a noble pursuit in itself, with the aim of one’s research to protect our planet. While undeniably important, rarely does work from our field receive the recognition afforded to Nobel Prize winners.

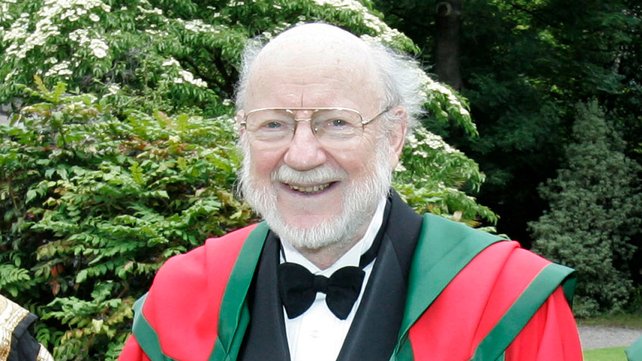

This year, the department of Zoology joined illustrious company in having one of our alumni named as a Nobel laureate. William (Bill) Cecil Campbell was born in Donegal in 1930. He studied Zoology at Trinity College Dublin, graduating in 1952, before beginning his PhD in the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

His research centered upon the field of parasitology, initially working on parasitic worms as an undergraduate with Professor Desmond Smyth, which, as Dr Campbell puts it, “changed [his] life by developing [his] interest in this particular field”. Upon completing his PhD, it was his work at the Merck Institute of Therapeutic Research on parasitic roundworms that led to the discovery of a class of drugs called avermectins with Satoshi Ōmura, that would help to control two of the world’s most debilitating diseases: lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis.

Lymphatic filariasis, more commonly known as elephantiasis, is caused by filarial nematodes, using mosquitos as a vector for the disease. They enter a new victim as larvae, which migrate to the lymph nodes of the legs and genitals, and mature into adults. When these worms die, they trigger intense inflammation. This blocks the flow of lymph, which accumulates under the skin, causing limbs and groins to swell to gigantic proportions.

Onchocerciasis, more commonly known as river blindness, is also caused by filarial nematodes, but of a different species. These are spread by blackfly bites, entomb themselves in deeper tissues, and release larvae that migrate to the skin (where they cause severe itching) and the eyes (in which they can cause blindness).

The avermectins that Campbell and Ōmura discovered, and especially their most potent member ivermectin, can control the symptoms of these diseases by killing the larval nematodes.

Unlike many drug discoveries of this magnitude, Dr Campbell’s employer, the Merck Institute of Therapeutic Research decided to release the drugs for free for those that need them. As a result of their altruism, their discovery reached potentially millions more people than would usually be able to afford such a drug. Although Dr Campbell is credited with floating the idea of releasing the drug for free, he insisted in a recent interview with The Irish Times that his chairman, Roy Vagelos be credited with making the ultimate decision on its release. In describing the decision, Campbell remarked “I think it was done because it was the right thing to do, and I think the employees applauded it, because they thought it was the right thing to do.”

In a typically understated fashion, and unlike some recipients before him, Dr Campbell never hoped to win this award. Instead, he dreamt of one-day curing malaria, a goal he feels is achievable to young scientists willing to keep an “open mind” to their research.

This award offers a timely reminder that the research carried out both within these walls, and when our alumni move on has the potential to make an impact far beyond our initial intentions. As Dr Campbell “The greatest challenge for science is to think globally, think simply and act accordingly. It would be disastrous to neglect the diseases of the developing world. One part of the world affects another part. We have a moral obligation to look after each other, but we’re also naturally obligated to look after our own needs. It has to be both.”

author: Dermott McMorrough, with thanks to Dr Celia Holland.

images: rte.ie, wikicommons.