- The remarkable bird life of the Wakatobi Islands, SE Sulawesi: hidden endemism and threatened populations - 10/07/2020

- The Bird Life of Wawonii and Muna Islands Part I: biodiversity recording in understudied corners of the Wallacea region - 30/06/2020

- Comparing the biodiversity and network ecology of restoredand natural mangrove forests in the Wallacea Region. - 09/12/2019

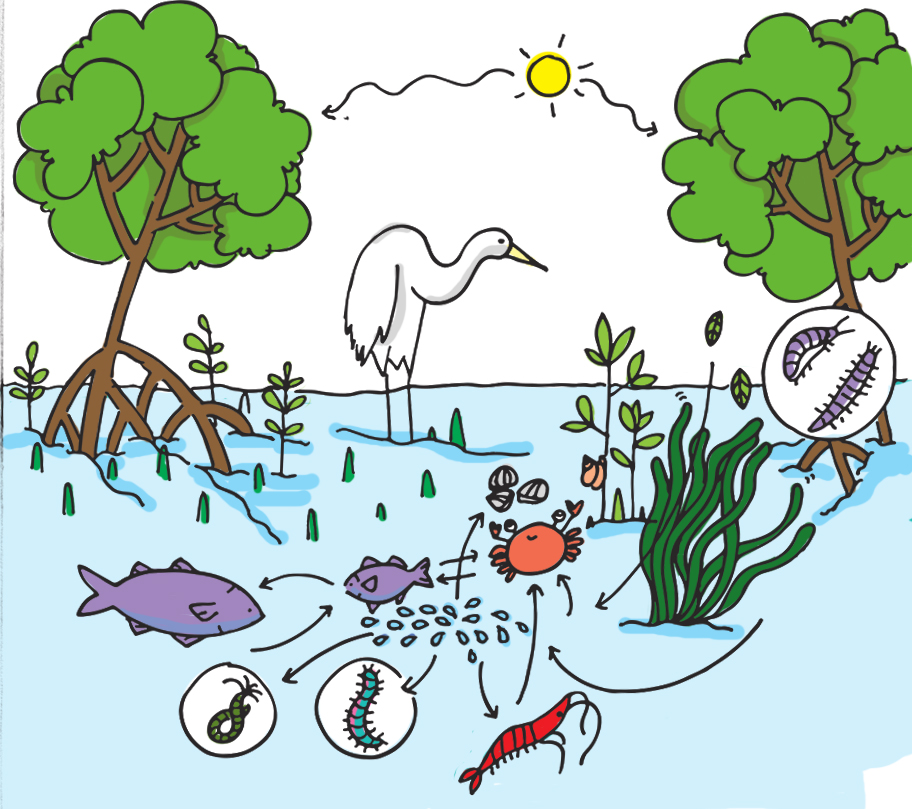

Habitat loss is the primary threat to most species, as humans convert ever more areas of the globe to intensive land uses for our purposes. While some of this is unavoidable, the unsustainable level of global habitat loss has caused great damage to biodiversity, the fight against climate change, and the local economy and culture of vulnerable communities in the poorest parts of the world. It is increasingly clear that slowing habitat loss will be not be enough to repair this damage, we must restore/rehabilitate lost and damaged habitat. This process is already happening in many areas where human use is no longer economical, such as abandoned mines, upland farms and elsewhere. However restoring an ecosystem is not a simple process, many of these projects fail, and the reasons for this are not always clear. There are no agreed standards for measuring the success of habitat restoration. However in the Newcastle University Network Ecology Group we believe that ecological networks may hold the key to monitoring and directing restoration efforts. As part of the CoReNat consortium we are seeking to use ecological networks to assess the success of mangrove forest restoration projects in remote Northern Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Mangrove forests are a uniquely valuable coastal wetlands in the transition zone between land and sea. They protect against coastal erosion, are a key carbon sink and sustain millions of people globally, However the loss of mangrove habitat has been severe, particularly in Indonesia, which has lost 40% of its mangrove forest in the last three decades. They are often removed for shrimp farms, however these farms become unsustainable after 5-10 years, leaving locals with no source of income. The Indonesian government has put large amounts of resources into restoring the lost mangrove forest to repair the traditional local economy (fishing, crabbing, low intensity lumber harvesting) and as part of efforts at using mangroves as a “blue carbon” store. However these projects have met with mixed success, and there is no clear template for best practice. This is where the CoReNat consortium comes in! We are a group of UK and Indonesian universities, funded by NERC, the Newton Fund and Ristekdikti as part of their Wallacea Biodiversity initiative. The CoReNat partners are comparing natural old growth and restored mangroves at sites in Northern Sulawesi, looking at various elements of ecosystem stability, services and biodiversity to assess whether the restored sites have replicated the complexity and function of the natural forest.

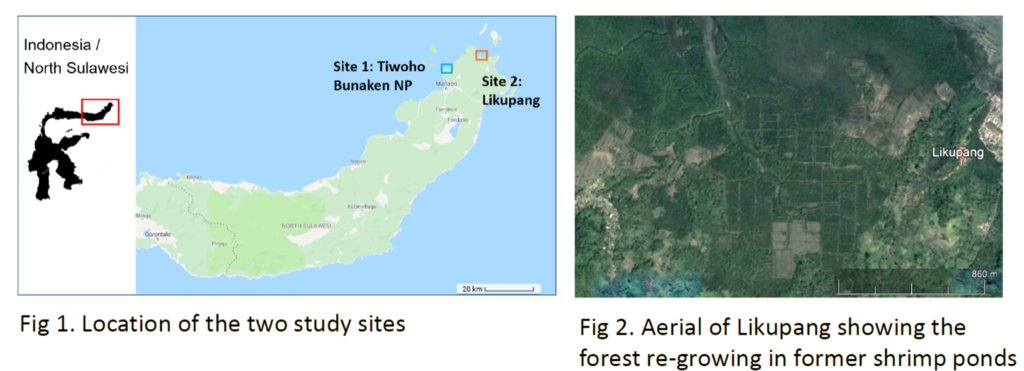

Our work will take place in two large mangrove systems in Northern Sulawesi, an estuarine mangrove at the northern tip of Sulawesi named Likupang and a fringing mangrove named Tiwoho, near Manado city. The great Alfred Russel Wallace himself visited Likupang and marvelled at this great tangle of mangrove forest. At both of these sites there are two different types of restored mangrove forest, a mono-culture forest where a single tree species was planted and a multi-species restoration where no trees were planted, the shrimp ponds were simply dug out and the sea walls were broken, allowing natural regeneration from mangrove propagules spread from the natural forest. Both of these restorations will be compared to the remaining natural forest, and each other, to see which, if any, method was more successful in replicating the natural system. This will allow us to help shape restoration policy going forward, highlighting the most successful and cost-effective methods.

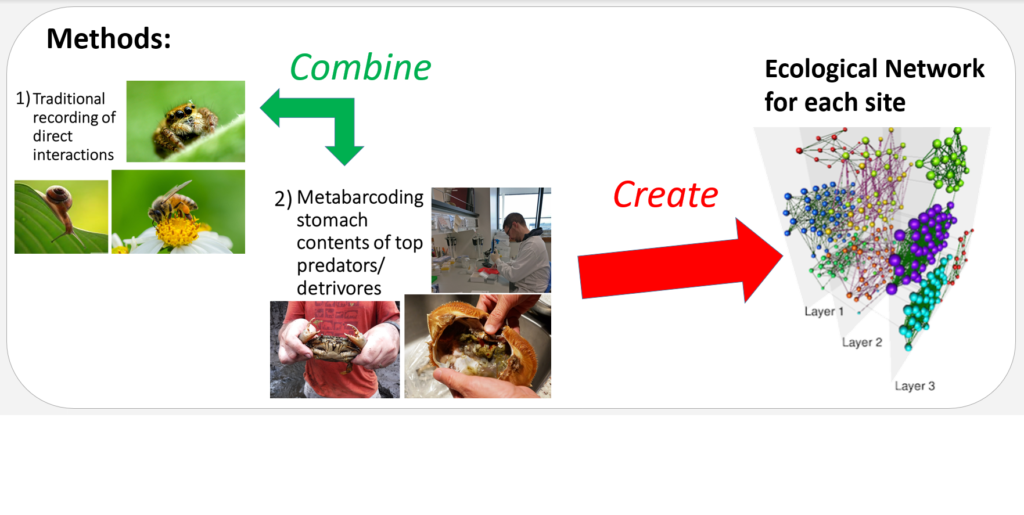

The Network Ecology Group’s role in this will be to assess and compare the ecological networks of the different sites. What are ecological networks you might ask? They are a representation of the biotic interactions in an ecosystem. This encompasses predation, pollination, parasitism, and even commensal interactions like a spider using a plant for its web. Therefore ecological network analyses allow us to assess how an ecosystem fits together and functions in unprecedented detail (Harvey et al., 2017). But how are those connections measured? This depends on direct measurement of interactions, which in our case will mean a lot of time up to our knees in mud in the mangroves!

In both the Likupang and Tiwoho sites, we are using an intensive regime of sampling in a series of quadrat plots to get a full picture of the ecological networks. We have replicated plots in the natural site, the mixed-species restoration and the mono-culture restoration, at both sites, to allow us to compare the success of restoration. The quadrats will be sampled both before the rainy season (already done) and after (still to come in March-April 2020), including catching of free living organism, sieving the sediment, vegetation searches and a series of traps and camera traps. This has allowed us to sample the animal communities in unprecedented depth. Also, on a personal level this has an incredible introduction to real mangrove fieldwork. Few ecosystems test you so thoroughly. The effort of moving even a couple of metres through a maze of prop roots, up to your knees in sucking mud, cannot be communicated. I won’t even get into the insane humidity and the voracious ants! The mangrove veterans tell me it either keeps you young or ends you!

This sampling will allow us to build complex multi-layer ecological networks, by combining direct observations of interactions, with meta-barcoding of the stomach contents of top predators and detrivores in the ecosystem (crabs). Meta-barcoding techniques allow many species to be identified from a sample (such as a stomach) using DNA barcodes. This innovation will allow us to construct much more complex networks and to allow certain key species to do much of the sampling for us! We aim to analyse the structure, complexity and robustness of mangrove ecological networks. This will allow us to determine species importance and any missing links, identifying whether previous restoration projects have failed because the lack certain key species. We believe this project will provide an important template for measuring the outcomes of restoration projects, both in Sulawesi and worldwide. We hope this will allow much more efficient restoration programmes to be rolled out in mangroves and other systems on a wider scale!

Mangrove sampling in a natural forest site

References

Harvey, E., Gounand, I., Ward, C. L., & Altermatt, F. (2017). Bridging ecology and conservation: from ecological networks to ecosystem function. Journal of Applied Ecology, 54(2), 371-379.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kementerian Riset Teknologi Dan Pendidikan Tinggi (RISTEKDIKTI) for providing the necessary permits and approvals for this study (330/ E5/E5.4/SIP/2019). We also thank our partner institutes Edinburgh Napier University, Sam Ratulangi University, Tadulako University, Diponegoro University and Northumbria University, and our funders NERC, the Newton Fund and Ristekdikti. Finally a huge thanks to all our field workers and assistants who have helped get this project up and running!

Photo credits: Darren O’Connell, Karen Diele, Marco Fusi and Zoe Dunnet