by Stephen Mulkearn

When Melissa Jeuken was appointed to her new job as a shepherd to a 25-strong flock of old Irish goats on Howth Head last September, the news caught national and international attention. A rare breed of feral goats was being employed in an innovative attempt to keep the heather in check to curtail wildfires at the Dublin beauty spot, a natural solution to an increasingly destructive environmental problem. Utilising ecosystem processes such as grazing livestock to restore biodiversity is second nature to Melissa who grew up on her father Harry Jeuken’s farm in Lough Avalla, Co. Clare. Burren farmers such as the Jeukens have for many years used the seasonal movement of grazing animals to maintain the landscape’s rich grasslands, whose range of wildflowers from orchids to gentians gives this special area of conservation its unique floral diversity. Over 300 Burren farmers are now paid directly to protect biodiversity under such results-based payment schemes (RBPS).

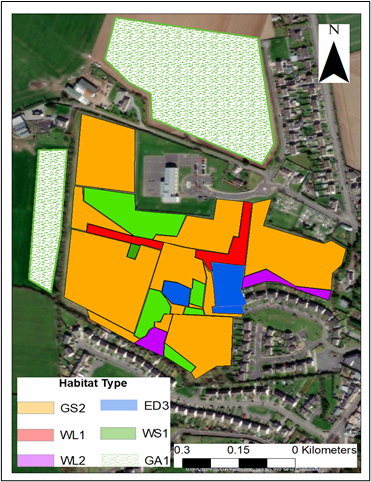

Following accession to the EEC in 1973, the modernisation of Ireland’s agriculture sector led to increased intensification and environmental problems – more agricultural pollution from run-off and fertilizer, erosion of upland areas from over-grazing and habitat loss from land-use change. The mid-1990s saw agri-environmental schemes such as REPS attempt to address the growing imbalance between intensification and environmental issues. In areas with unique landscape features such as the Burren, however, the one-size-fits-all approach of REPS was found wanting, with a lack of buy-in from local farmers who felt the Burren’s unique set of needs were excluded. This led to one of the first RBPS in Ireland in 2004, the Burren LIFE programme, funded under a European Union scheme for climate action and the environment. There are now at least 8 other RBPS, whose efforts to conserve species range from the corncrake and hen harrier in the northwest and mid-west to the pearl mussel in the south. The majority of schemes are located in the west as a larger proportion of high nature value (HNV) farms are found there.

RBPS come under the general umbrella of Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES), of which there are hundreds globally, and are viewed as an important component of farmland biodiversity conservation not least because they directly involve farm owners in the protection of important ecosystems. However, a criticism of early agri-environmental schemes such as REPS was that payments to farmers were not yielding biodiversity results. So are RBPS any different?

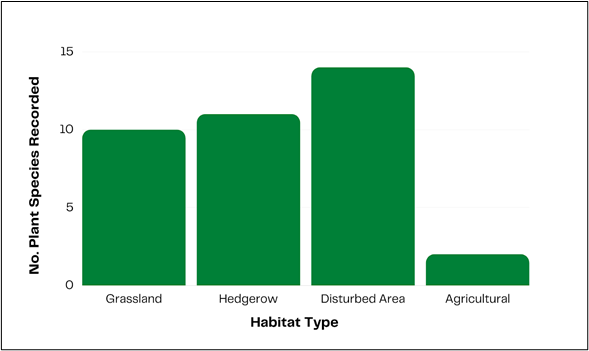

There are accepted pros and cons to the results indicators used in scorecards indicating ecological integrity in RBPS. The indicators have worked well in the Burren,

where scores have risen for fields assessed and this has directly led to improvements in the conservation of species-rich grasslands. The presence of nests is an indicator of the conservation of farmland birds, and this is seen as a beneficial element of the scheme as it raises awareness of biodiversity among farmers and builds ownership. However, the presence of a nest does not guarantee chicks will fledge successfully. Therefore, the conservation outcome for any particular results indicator may not always be transparent, causing challenges when it comes to assessing the biodiversity impact.

Indeed, annual survey results for hen harrier reveal a 25% decline in the bird’s six habitat ranges since being designated within a Special Protection Area, with the burning of heathland and land-use change to forestry and windfarms the chief causes of the decline. On the other hand, changes in farmland practices such as delayed mowing initiated through Corncrake LIFE may be producing, in the absence of scientific studies, at least anecdotal increases in corncrake numbers.

With a third of Ireland’s farmland definable as HNV, the potential exists for RBPS expansion. HNV areas also include half of the country’s Natura 2000 sites, meaning efforts to increase the uptake of RBPS would also assist with the management of designated sites. However, there is a need to develop reliable indicators to assess improvements in farmland biodiversity and the mechanism may not exist within existing RBPS to achieve this.

The principles underpinning RBPS – locally-led, farmer-centred, results-based, adaptable – make them attractive for wider agricultural adoption only if more flexible structures are introduced in national and international policies. Environmental NGO reaction to the latest round of Common Agricultural Policy strategic planning has been unequivocal on the ongoing biodiversity challenges, with BirdWatch Ireland asserting that only between 2 and 5% of the €9.8 billion Irish CAP budget will be spent on ‘effective measures for biodiversity’ and that targeting of actions on HNV farmland, in particular is required. And these concerns seem justified. A 2020 study of the effects of increased afforestation found 13 of 44 birds of conservation concern had over 80% of their habitats afforested, resulting in a shift in avian community composition there.

RBPS are locally-led, multi-stakeholder conservation interventions which work from the bottom-up and include local communities in decision-making. They are an important, albeit currently marginal, element of the EU’s strategy to conserve biodiversity in agriculture. Being a relatively recent development, their contribution to restoring biodiversity has yet to be adequately quantified on an EU-wide scale. That they are producing initial positive results in certain locations may help avert further extinctions brought about by Ireland’s ensuing biodiversity crisis. However, with most Irish farming taking place outside HNV areas, the effect of RBPS on restoring biodiversity may be limited nationally, and many farmers could still find themselves choosing between continued intensification and abandonment as a result of current EU agricultural policies.