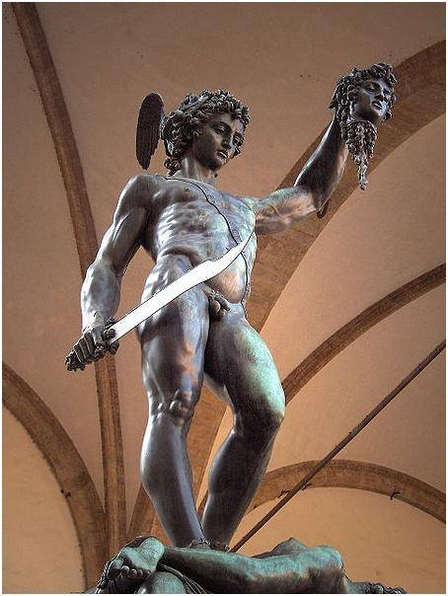

Most people have heroes. As this is a science blog I’m guessing you are already battling out Captain Kirk vs Spock, Batman vs Spiderman or Inspector Gadget vs MacGyver, in your head in order to choose the most appropriate hero. But here, I mean academic hero. That person whose work becomes the foundation of our academic thinking or that we simply admire for their lifetime academic achievements. Deciding on our academic hero makes a great conversation topic and it usually ends up covering pretty much the whole history of science. In my lab, there is an ongoing interest for academic heroes. Some of us would even secretly (or not) like to have a bobble head of our academic hero.

As I work in a mostly theoretical lab whose research is pretty broad, ranging from fisheries, to social evolution and behaviour (some lab members, when asked, simply reply “ecology”), it is not surprising that our academic heroes are not the same person. Even agreeing on what could constitute one, is sometimes controversial. Some scientists just have to be heroes, for example Darwin would be in most academic’s top five for his theory on natural selection, and so would Watson and Crick for the discovery of the DNA double helix that changed the way we do science. But few people would contest their achievements are worthy of the academic hero title and consequently not much fun for a bobble head. Others, in fact most, are surrounded with pro and con arguments and we must be passionate enough to defend them (as we would for Spock). For example, Richard Dawkins is a name that pops up in the blogosphere quite often as an academic hero, not because of his forefront ideas but for popularizing evolution, a hot topic among the public. Should he be a contender for academic hero? Surely Carl Sagan who made cosmology popular is.

My academic hero, which I shall not name as I might meet him someday and I don’t want to appear a ‘fangirl’ (which I am but doesn’t sound very professional…), amazes me for the numerous ideas and frameworks he put forward in many different subfields. Those ideas and frameworks are perhaps not recognized as important as DNA or natural selection, and many have been rebutted already. However, without them, the progress in ecology and evolution would have been much slower and would likely have taken a different route, i.e. he shaped the field. In my view, he is definitely bobble head material! I’m generally a shy person and a few years ago I missed the opportunity to meet my academic hero in a conference to shyness. How do we go about introducing ourselves to our heroes? Imagine going to Batman and saying “Hello, I LOVE the way you save the world, could you sign my bat-shirt please?”

We always read about tales of people meeting their heroes and generally something embarrassing happens… have you met you academic hero? Tell us your tale.

Author

Mafalda Viana: vianam[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit

wikimedia commons