By Ed Straw

There’s a common perception among environmentalists that farmers are pretty fast and loose when it comes to environmental regulations. Farmers have to follow endless rules on when they can cut the hedges, where can’t they spread slurry and how to apply pesticides. If farmers are drowning in red tape, surely they can’t be following all these rules all of the time?

There’s a particularly large burden of rules when it comes to pesticides. This makes a lot of sense as pesticides are potent chemicals, specifically engineered to be toxic to some kind of life form. When mis-used, pesticides can contaminate food chains, water courses and even cause serious illness in humans. So, if farmers aren’t following the rules on pesticide applications this could have some pretty disastrous consequences for their own health, as well as for biodiversity. We set out to answer this question by surveying Irish farmers and simply asking them if they follow the rules.

The surprising answer we found is that the majority of farmers are following the rules most of the time. When we scored farmers on how well they followed the legally required steps for pesticide applications, the average score was 81 out of 100, which is pretty good! A key question that worried me as a pesticide scientist was whether farmers were spraying their pesticides at the right concentrations, which 96% of respondents said they were. Farmers also reported being very good at disposing of their leftover pesticides i.e., not pouring them down the drain, which is something that worries aquatic ecologists given watercourse pollution is a serious threat to river species.

In fact, in most of the questions we asked, the majority of farmers were following the rules. So, the perception of the average farmer being a rule-breaker and doing whatever they like with pesticides is a myth! That said though, we did see some areas where a sizable chunk of farmers weren’t following the rules properly.

Prior to applying farm pesticides, there’s a mandatory two-day training course covering the basics of how to use the kit and how to stay safe. We found that 1 in 6 farmers who use pesticides professionally admitted to not having taken this course, which both illegal and worrisome.

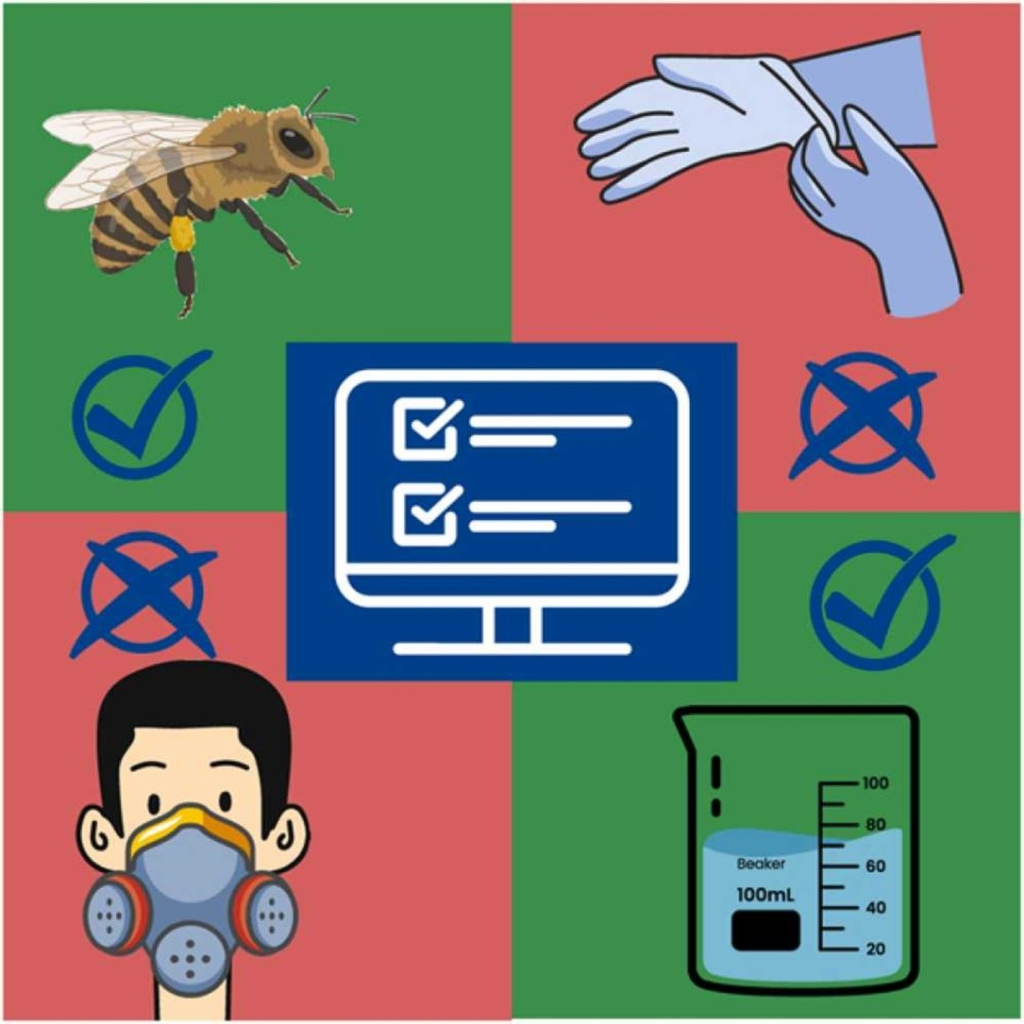

Beyond training, another key tool in protecting farmers from pesticides is personal protective equipment. Things like gloves, masks and overalls. This is sadly the worst area for compliance with the rules, as around half the farmers in our survey were bad at wearing protective equipment while spraying. This means they are potentially exposing themselves to dangerously high levels of pesticide. Gloves, which are the easiest piece of protective equipment to source and wear were worn by most farmers, but still 1 in 4 ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ wear gloves while mixing and applying pesticides.

Beyond these sizable minorities putting their own health at risk, we also had the odd instance where one or two respondents admitted to some behaviours which could be really bad for the environment. These included reports of dumping of leftover pesticides in ways which would contaminate rivers, or even admitting to buying banned substances like neonicotinoids.

So while the overall picture is that most farmers follow the rules most of the time, there is still some work to be done. Principally in supporting farmers in wearing their protective kit and reaching and educating those few farmers who aren’t following the rules properly.

It’s worth briefly contextualising these results internationally, as the situation in the developing world is very very different. In China, Africa and the middle east, the scale of rule breaking in an order of magnitude greater than among Irish farmers. There are very frequent reports of pesticide overapplication, dumping of pesticides into waterways and little protective equipment being worn. This shows the successes of European and Irish efforts to develop agriculture and to regulate pesticides stringently.

Now having said all that, the obvious response is ‘are you sure the farmers weren’t lying?’. And we can’t directly test this, but there’s actually a wealth of sociology literature which says that if you give people anonymity and a non-judgemental questionnaire, they’ll be surprisingly honest. Among scientists even, if you use a well-designed survey, around 2% will readily admit to making up data (rather scary!). We used an online survey because it allowed us to afford our respondents total anonymity. While our survey is likely to have encouraged honesty, the best evidence for honesty comes from the number of farmers who admitted to breaking some form of rule. If our farmers were all lying through their teeth about not overapplying pesticides or breaking other serious rules, why would they admit to breaking the rules on wearing personal protective equipment?

To conclude, despite popular belief, farmers are good at following pesticide rules. While there are a few rule breakers among them, broadly speaking farmers are using pesticides properly. The main area they struggle in is protecting themselves. Governments should support farmers more in education on why following the rules is important, and should continue to pursue high standards in how they are used.

If you want to read these results in full, see our free to read paper “Self-reported assessment of compliance with pesticide rules” at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.114692. It was as published in Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, in April 2023.

Follow Ed on Twitter @EdStrawBio

Edited by Luke Quill