You may have heard on the academic grapevine that I will soon be leaving Trinity College Dublin. As with all moves I’m both sad to be leaving, but excited to take on new challenges. I’ll be around until the summer, but now this is common knowledge I wanted to explain why I’m moving on. And also to make something else really clear – I’m not leaving because I dislike working here! The School of Natural Sciences (and particularly Zoology where I’m based) has been a fantastic place to work for the last three years. The staff are friendly and supportive, the students are top notch, and the working environment here is energetic and collegiate. I’ve met some amazing people and I hope to continue working with them. I’ve also learned more than I thought possible in just three years.

You may have heard on the academic grapevine that I will soon be leaving Trinity College Dublin. As with all moves I’m both sad to be leaving, but excited to take on new challenges. I’ll be around until the summer, but now this is common knowledge I wanted to explain why I’m moving on. And also to make something else really clear – I’m not leaving because I dislike working here! The School of Natural Sciences (and particularly Zoology where I’m based) has been a fantastic place to work for the last three years. The staff are friendly and supportive, the students are top notch, and the working environment here is energetic and collegiate. I’ve met some amazing people and I hope to continue working with them. I’ve also learned more than I thought possible in just three years.

Then why am I leaving? Mostly it boils down to the “one body problem“. We’re all familiar with the “two body problem”, whereby people in a relationship are forced to find ways to make their relationship and careers work at the same time. Sometimes this involves partners trying to get jobs in the same place, although it could be detrimental to their careers; other times people live apart so they can have more choices over which job to take. Either way it’s a crappy problem and I feel terrible for people in that situation. We talk less about the “one body problem” which also disproportionately affects women and minority academics, particular LGBT academics. I also believe it may be an important reason why these groups leave academia so I think it deserves more attention when we’re thinking about equality.

The “one body problem” refers to the difficulties single academics face when moving around for jobs. In its own way this can be just as bad as the “two body problem” (it’s often quite frustrating when people tell me how lucky I am to be single and free to move about). Arriving in a new place as a single person is daunting and, without the support network of a partner or friends, it is also extremely isolating. Making friends in a new place takes time, and the heavy workloads of academic jobs leave little time for friend making attempts. Added to this, academics are very transient so it’s not unusual to make a new friend, and for that friend to leave just a few months later (in Dublin even the non-academic community is fairly transient). This is particularly hard for international postdocs who don’t have family or friends living nearby to escape to at the weekends. The other issue with the “one body problem” is that eventually most single people would like to meet someone, even if they’re currently happy living an independent life. In some places this is next to impossible, for example, tiny college campuses in the middle of nowhere, and gets harder as people get older. Again this disproportionately affects women and minorities.

I’ve found this problem has become worse for me in recent years. I think this is partly because of my change in job status. As a PhD student and a postdoc I had far more free time to try and make friends when I moved. There were also lots of social events organised for students/postdocs where you could meet each other, and also form a bit of a community. This sort of thing is less common once you’re a professor. Also I’m now the one staying put as the postdocs and PhD students I’ve befriended move on to other places. It also reflects the fact that most people my age are married with kids, particularly the younger faculty here. We get on really well at work, but at 4pm everyone goes home. Eventually I realised that this situation was causing me a considerable amount of stress and unhappiness which was only going to increase as the friends I’ve made in the last three years prepare to finish their postdocs or PhDs and move on. So I’m leaving Dublin because I don’t have a stable support network here and in the long term that is not a good thing for me (or anyone).

If you have new single people joining your department I hope you’ll try and help them to settle in and don’t just assume that being single is the easy option for academics! Note that I’m not saying the “two body problem” is easier! Let’s just recognise that the academic lifestyle is hard for everyone and try to consider how to make things more equal for all women and minority groups, not just those with two body issues, and/or children.

Author: Natalie Cooper, @nhcooper123, ncooper[at]tcd.ie

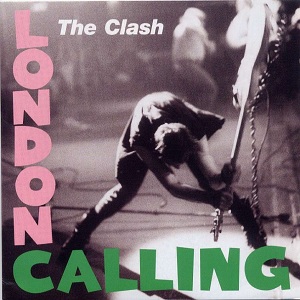

Photo credit: “TheClashLondonCallingalbumcover” by Source. Licensed under Fair use via Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:TheClashLondonCallingalbumcover.jpg#mediaviewer/File:TheClashLondonCallingalbumcover.jpg