The word “Morphometrics” was already mentioned on this blog here and here. It’s a horrible term which nevertheless describes a really cool field in evolutionary science…

Today we’re having a workshop with François Gould (@PaleoGould) so hopefully everyone will know more about all things morpho by the end of the day. I won’t go into the juicy details of procrustes analyses, elliptic Fourier transform or other Bezier polynomials (see Zelditch and colleagues “Geometric Morphometrics” book or Julien Claude’s excellent “Morphometrics with R” for further details about these friendly terms). Instead, I’d like to talk about one aspect of data collection.

In a simplistic way, morphometric data can be sorted into two categories. Two dimensional data, such as linear measurements or shape outlines, can be obtained in many ways, from trusty calipers (which are digital these days) to computer measurements of landmarks placed on pictures (see here for a nice list of usable software). The second type of data is obviously 3D data which, again, may be collected in many ways using fancy technology from digital microscribes to medical CT-scanners.

I use a surface 3D scanner like this one which has a fairly well defined list of pros and cons.

-Firstly, it is way more time consuming to scan specimens than to use either 2D methods or a 3D microscribe. My scanner takes roughly one hour per skull.

-Secondly, the scanner is quite expensive even though the final scans aren’t always completely accurate and may have problems of poor quality.

Despite these problems, I’ve found that, in the end, the list of pros is much longer!

-It is really easy to use the scanner and, even if the price is not cheap, it’s far from unaffordable.

-The data you get from a scan is easily transportable and therefore easily sharable; think about posting or e-mailing a skull! I think this point is really important when you are studying fossils. You can usually find skulls of most living primates in any natural history museum but fossils are really rare and specimens are only housed in a few places so access to 3D scans would be a great asset to interested researchers.

-Another point linked to this sharing idea: it is more scientifically friendly since you can put your scans into online supplementary materials and publish them with your papers.

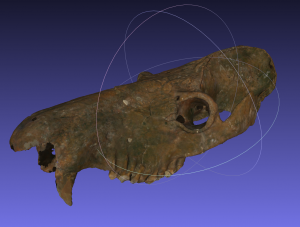

-Furthermore, even if it’s a less technical point, 3D scans look pretty amazing and are excellent illustrations for your papers like this 3D ring-tailed Lemur skull:

This list of pros and cons can continue on ad infinitum and ultimately all morphometric methods have both advantages and disadvantages of one kind or another. Aside from all these technical details, I think that the best part of using a scanner is the chance to play with lasers! It’s just so cool to be measuring skulls in a museum with a normal set of calipers while your scanner spits out lasers in all directions and then, by magic, the giant lemur (Megaladapis) on the desk is there staring out from your computer screen.

Author

Thomas Guillerme: guillert[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit

Thomas Guillerme