After rereading Sive’s excellent blog post on what is a zoologist or at least what is it like to study it, I remember having a slightly similar difficulty in explaining my background in palaeontology. Reactions range from: “Oh… Palaeontology? That’s like the origins of humans and stuff?” or “So you go on excavations and find ancient Roman pottery?” to “Bheuuh, want another beer?”. What frustrated me is that none of these reactions are correct but neither are they totally incorrect (especially the last one!).

Palaeontology is not archaeology

Most people that have only a vague idea of what palaeontology is are usually not big fans of Jurassic Park and don’t know Alan Grant so they usually associate palaeontology with Ross Geller or Indiana Jones. Being not a big fan of TV series, I don’t know whether Ross is a good representation of the reality of life as a palaeontologist but I know that Indiana is not. Not even a little bit. He’s an archaeologist. That might be a nerdy detail for some but to understand what palaeontology is about, it is important to understand the difference. Even though both archaeologists and palaeontologists study the past based on what they find in the ground (and in books!), the time scales involved make the two disciplines impossible to compare. Archaeologists are mainly interested in human culture (they might find animal bones but they are usually the fragments of crafted objects). In contrast, palaeontologists are interested in the remains of life that occurred before human civilisation. Therefore we have two very different time scales here: from years to centuries or, at a push, millennia for archaeologists and from hundreds to millions of millennia (or billion of years) for palaeontologists.

Palaeontology is not about excavations

Palaeontologists do not excavate fossils, that’s a job for Oryctologists. Okay, I’m being picky with the terms here but, again, the distinction is important. Most palaeontologists are also oryctologists, meaning that they go into the field and do excavations as the basis for their scientific work (yeah, in the end, that’s not a cliché, one of the nicest parts of the job is field work!). However, not all palaeontologists are oryctologists (even though most are) and many oryctologists are not palaeontologists. Again, palaeontology is not only about digging up fossils and putting them in museums (contrary to what this song suggests), it is about the study of changes that occurred on our planet through deep time (geography, climate, etc…) and how they affected living organisms (evolution, extinction, etc…).

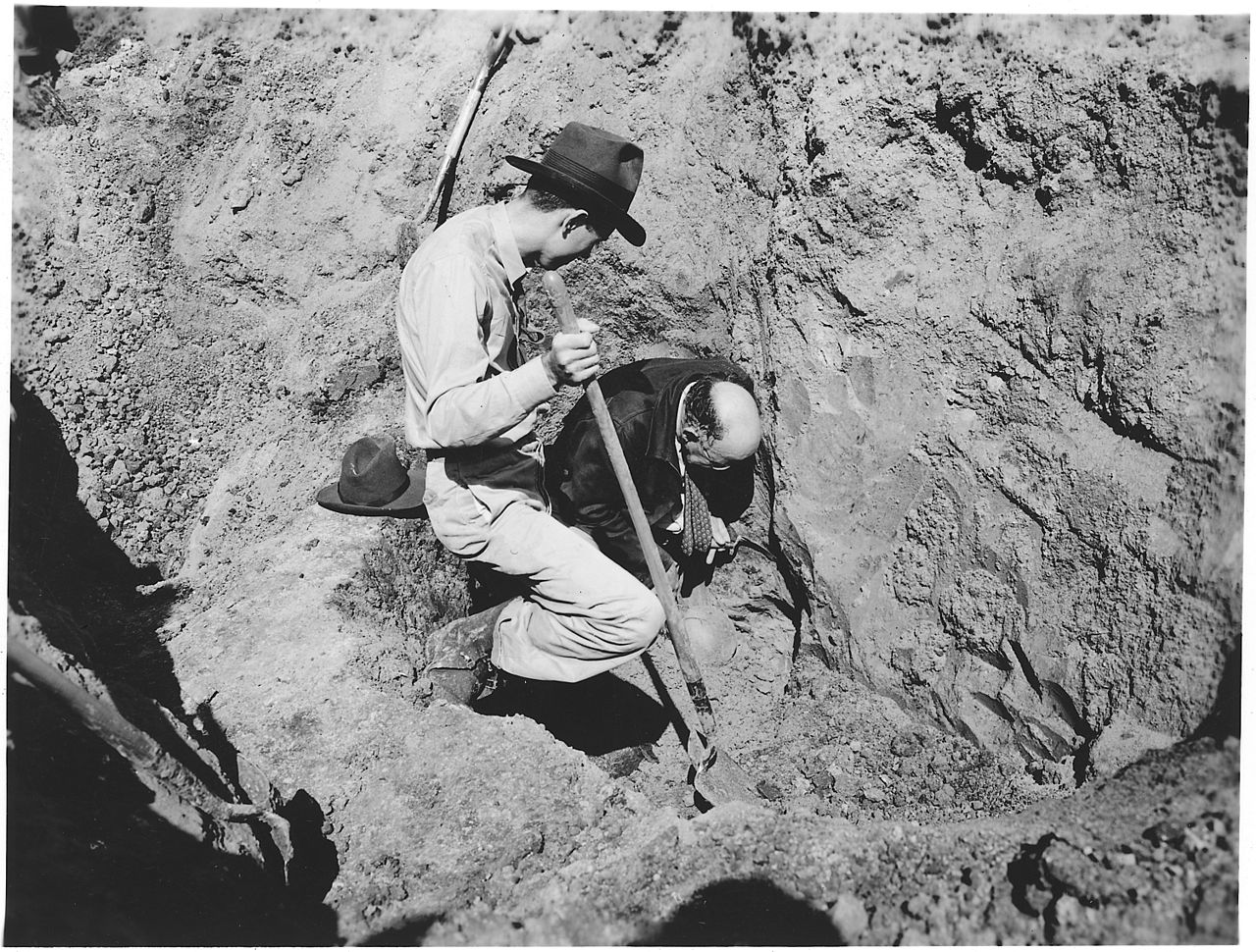

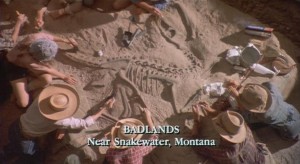

While we’re on the subject of oryctology, there is a huge public misconception about excavations. Most people that have seen Jurassic Park might think that, in the 90’s, one could just go into the field armed with nothing but a paint brush and happily stumble across a complete Velociraptor (Deinonychus!) skeleton which just had to be cleaned out from the surrounding layers of dust. This scenario would certainly make palaeontology way more straightforward and easy but it would also mean that excavations would be just boring routines where a hoover would do a better job than a naively enthusiastic undergrad student!

Even though excavation techniques are at least as numerous as excavation sites, the paint brush must be one of the rarest tools. Personally, I’ve tried things like hammering a cliff with a pike, shoveling dust and blocks of stone, digging in solid clay with an oyster knife or sifting tons of bags of sediments after diluting it in acid in a lab. None of these activities are similar to the restful act of flicking away sand with a brush (but they’re still a lot of fun!).

Palaeontology is not dusty

The two points above are understandably confusing for the general public because of the Hollywood image of palaeontologists, depicted as “adventurers, not really serious, but entertaining” (to translate a quote from Eric Buffetaut’s book “À quoi servent les dinosaures?”). One might think that other scientists would have a better understanding of palaeontology. However, even if they generally understand the discipline and its implications better than the general public: “Paleontology has a reputation as a dry and dusty discipline, stymied by privileged access to fossil specimens that are interpreted with an eye of faith and used to evidence just-so stories of adaptive evolution” (Cunningham et al 2014).

Thankfully, however, the discipline that studies traces of evolution has not escaped evolution of its own. The “privileged access to fossil specimens” has been replaced by either huge online databases (just one example and one other among thousands) or accessible and well-curated collections. The “eye of faith” has been replaced by X-Ray tomography, Surface scanners and synchrotrons; and the “just-so stories” are now replaced by integrative studies leading to a new vision of the history of life…

Palaeontology is… great

The differences between a nerdy “Indianajonesomorph” oryctologist that knows all of the dinosaurs’ names by heart and a realistic palaeontologist are what makes palaeontology so interesting. More than the taxonomy, taphonomy, comparative anatomy and cladistic tools that palaeontologists use, palaeontology is about the idea that everything is constantly changing and that we live in just one fleeting moment in the vast history of life.

However, I still like the image of the “adventurers, not really serious, but entertaining”… As long as palaeontologists don’t take this image seriously themselves!

Author: Thomas Guillerme, guillert[at]tcd.ie, @TGuillerme

Images: Wikicommons