In biology and among biologists, we like to use terms that we know are not correct but that still come in handy when you’re confident that your interlocutor understands them the way you do. I’m thinking of terms such as “key adaptations”, “living fossils”, etc… However, among them, there is one that particularly bugs me and makes me feel like Samuel L. Jackson in the iconic Pulp Fiction scene and that is: “the rise of the age of mammals”.

Recently, Barry Lovegrove and his students published a nice data driven paper in Proceedings of the Royal Society B on the hibernation of tenrecs. The team found that these amazing creatures (I refer you to Sive’s posts, our tenrec expert) do go into hibernation for 9 months straight even though they live in tropical latitudes. The paper first sparked my curiosity because of this new tenrec fact but also due to the spin that the authors put on the paper’s results. They create a broad significance for the implications of their research on hibernation in tenrecs by describing their potential applications for how we might biologically programme astronauts to hibernate on a journey to Mars.

But what struck me the most (and I’m coming to main point of this blog post) is that the authors place their paper in the context of our understanding of the K-T boundary event which, they argue, was a key event in the evolutionary radiation of placental mammals (according to work by O’Leary and colleagues discussed here and here). And from there, the authors claim that tenrecs’ “predation-avoidance hibernation may be an ancient plesiomorphic characteristic in mammals and is a legacy, perhaps, of the 163 Myr of ecological suppression by the dinosaurs. It enabled the ancestral placentals, as well as the marsupials and monotremes […], to endure the short- and long-term devastations of the K-Pg asteroid impact, a capacity which is possibly the sole explanation for the existence of mammals today.”

This suggestion is based solely on their findings about hibernation in tenrecs. Their rather crude extrapolations to what these results tell us about the origin of placental mammals are mainly based on two erroneous assumptions:

-(1) they “report a plesiomorphic (ancestral) capacity for long-term hibernation that exists in an extant, phylogenetically basal, tropical placental mammal, the common tenrec”

– (2) “The long ca. 160 Myr stint of the nocturnal, small, insectivorous mammal was over, and gave way to the age of the mammals, the Cenozoic” because of the “Ecological release from the vice grip which the dinosaurs held over Mesozoic mammals”

(1) Tenrecs are Afrotherians. They are a sister group of golden moles and nested somewhere within the elephant shrews and aardvarks clade that is sister to the elephants, hyrax and sirenians (so, even within Afrotherians, tenrecs are not particularly basal). Afrotherians are a sister group to either Xenarthrans or Boreoeutherians (depending on the genomic region) but all three together form the extant eutherians. It is mistaken to interpret tenrecs as a “basal” mammal clade. The authors claim that their “hibernation data show some affinities to the ‘protoendothermy’ first noted in echidnas, suggesting retention of plesiomorphic characteristics of hibernation on Madagascar through phylogenetic inertia”. This implies that this hibernation characteristic has been lost in all other mammal groups .Using basic principles of parsimony, it would make more sense to attribute this hibernation characteristic to being yet another example of a convergent trait in tenrecs, not an ancestral state which was lost in most other mammals.

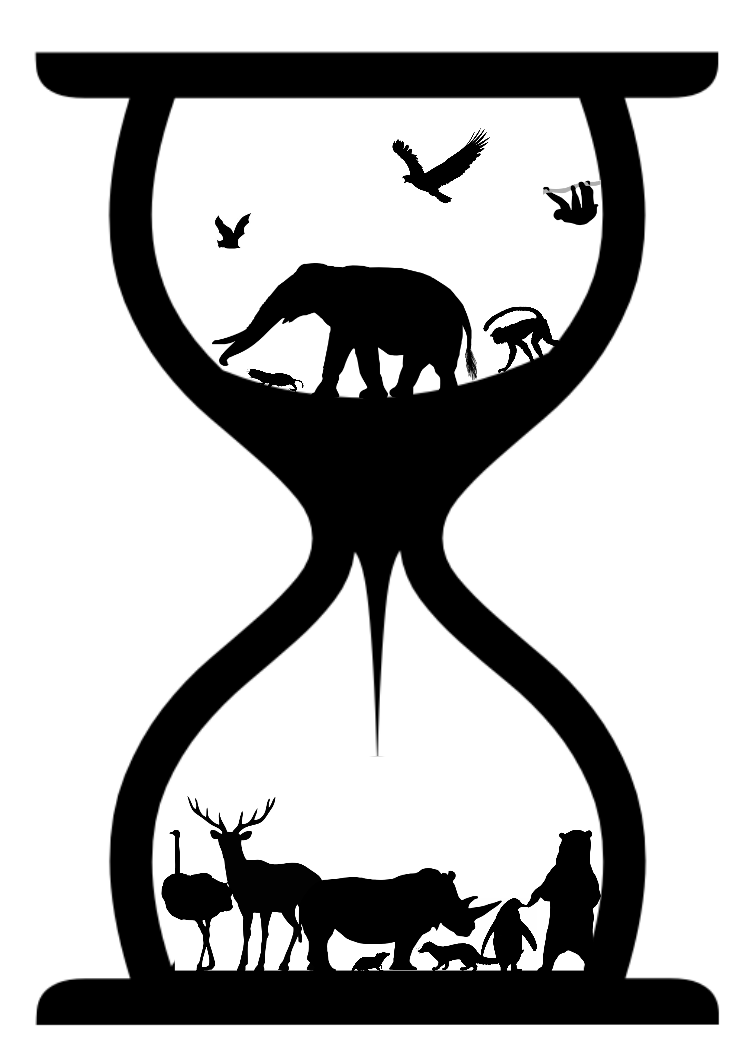

(2) I grew up reading a steady diet of books about the history of life. These presented a nicely summarized picture: around 65.5 Mya (now updated to 66 Mya, a small detail that can easily be fixed), all dinosaurs went extinct because they were too big and too stupid and the clever small mammals survived without any problem, liberated from their domination by the big stupid dinosaurs. This vision was awesome as a child; it had all the elements for a really anthropocentric/biblical view of the story (think about the Exodus) and clearly explained why mammals are the dominant species today. It even explains the success of humans: we used our cooperation and intelligence to reach our dominant position as head of all the mammals.

However, this romantic vision of the history of life (driven by paleontological data prior to the amazing discoveries of new Jurassic and Cretaceous mammals in the 90s and 2000s and the advent of molecular phylogenies) has, thankfully, been updated to integrate the last two decades of excellent work. This lead to a picture that is less romantic and more complex. The dinosaurs didn’t really disappear and are actually still more numerous (species richness-wise) than mammals nowadays. Similarly, the placental mammals and their ancestor didn’t just “bloom” after the K-T boundary event: they had their origin back in the late Jurassic, roughly at the same time as the dominant tetrapods of today (the birds), and they radiated multiple times: mainly due to global climatic changes during the Paleogene such as the “Grande Coupure” or the PETM…

I’m not sure why the authors chose to adopt an outdated vision of the evolution of mammals to introduce their work but it seems a pity to me that such a spin is necessary to present good work on unknown/understudied groups even if they’re as cool as tenrecs!

Author: Thomas Guillerme, guillert[at]tcd.ie, @TGuillerme

Photo credit: http://www.smbc-comics.com/?id=1535