As scientists with access to hundreds of peer reviewed journals its easy to forget that we are a privileged bunch. We get to read science straight from the horse’s mouth without anyone to get between us and the research. Yet for the majority of people journals are hidden behind paywalls and even open access journals remain largely the domain of working scientists if for no other reason than reading scientific journal articles is hard work. They demand a high level of prior knowledge and often use terms that are completely meaningless to anyone outside their field. It’s no surprise that the majority of people get their science news from newspapers.

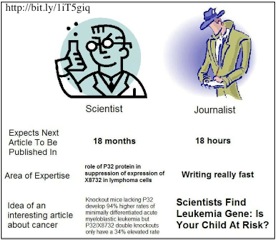

The problem with science in newspapers is that it’s really badly done. It’s often based on press releases from universities and others have written about how the media will take a story and run in whatever direction they please, regardless of the actual research. Science journalism has been relegated to the side-lines. While it would cause outrage if someone who knew nothing about football was allowed to write in the sports section, non-science journalists are regularly writing science stories, unable to critique the work or put it in any context. On the one hand it leads to sensationalist stories but on the other it can result in the real news story being buried among trivialities (something I’ve written about before).

It’s one thing to disagree with a news story about your own research but what about other science stories? If you have any interest in science chances are you’ve read a news story and shook your head in disbelief at the poor reporting. You may have moaned about it to friends until they wondered off saying something about “letting it go” or “getting a life”. But what, really, can you do? You’re just one person. . .

Well, it turns out there is something you can do. You can email the journalist. You can explain, politely and calmly, exactly what was wrong and then suggesting ways of making the story better. So, rather than say;

“Your article was rubbish, you don’t have any idea what you’re on about it was all wrong!”

you could write,

“I was disappointed by your article. You said that whales are a fish when they are actually mammals”.

(Hopefully you won’t see any errors that egregious!)

You may be thinking that it’s all very well and good to email them, but why should they listen? Why do they care? The story’s finished, they’ve moved on. Well, one reason is that most stories are online where they form a permanent record, so any errors will remain forever unless corrected which does nothing to help a journalist’s reputation. Secondly, most of the errors aren’t out of spite or even callous disregard, it’s because they don’t know any better. As I said, a lot of science journalists aren’t experts so they’re going to make mistakes. Even if do have a background in science they can’t know everything. Could you write as well on quantum mechanics as you could on evolution, for example? I doubt it.

This all sounds wonderful. You see an error in a science story, you email the journalist and he corrects it and everyone goes merrily on their way. Really? Life isn’t that pleasant. Well, actually, it can be. The inspiration for this post came from an article I saw hyperbolically titled “New species of terrifying looking ‘skeleton shrimp’ discovered”. The original article gave no information about who had discovered the animal or why it was important. It also had incorrect formatting on the genus and family names. I emailed the author and politely explained the problems. I had a lovely response and he corrected the formatting errors, added the information it lacks and, most importantly, gave credit for the discovery where it was due. The article now online is the amended one and while still not brilliant, is much better.

The moral of this story is that if you see bad science in the news contact the journalist. Chances are they don’t know they’re making mistakes and as long as you are polite and specific they will heed your advice. While you won’t get a 100% success rate, or even a 100% response rate, you will get some response. Focus on the smaller articles usually written by people low down the hierarchical food chain who are most receptive, who haven’t been jaded and welcome polite, constructive advice and can be encouraged to do better in the future. If we all make the effort to correct bad science reporting we can hopefully help journalists and improve science understanding in the public domain. Not bad for one email.

Author: Sarah Hearne, hearnes[at]tcd.ie, @SarahVHearne

Image Source: blogs.discovermagazine.com