The TCD Botany-Zoology Postgraduate Symposium made its annual return this month on the 7th and 8th of March for its 13th edition. This is a time when postgraduates and research assistants from the departments in the School of Natural Sciences could showcase their work and gain valuable experience presenting to peers. There was a diverse range of talks spanning from climate change, to fossilised plants, and a post-doctorate discussion panel. We also had the pleasure of hearing from the two keynote speakers Anja Murray who has had an extensive career in policy and media and talked about her expansive career and her new book. Secondly, Dr. Cordula Scherer works with the Trinity Centre for Environmental Humanites and is currently in charge of the IRC funded project Food Smart Dublin. She discussed branching the gap between science and humanities.

Day One

The first day kicked off at lunchtime on the 7th with a fascinating talking from Anja Murray. She started by discussing how her early career was mainly in policy making, aiming to make a difference with her ecologist perspective and knowledge. She then discussed her move into media hosting RTE’s “Eco Eye” for 11 years before its ending, writing “Wild Embrace: Connecting to the Wonder of Ireland’s Natural World” during lockdown, her podcast “Root and Branch” and weekly piece “Nature File” on RTE Lyric FM, and her column in the Irish Examiner. It gave us a great perspective on how to communicate what we, as scientists, know to a broader audience.

In the afternoon we heard from Thibault Durieux a third year PhD student who talked about analysis of plant stems to reconstruct plants from the early Carboniferous period. Next was Niamh McCartan a third year PhD who discussed how cold snaps can influence disease in the Daphnia system. Following Niamh, was Ian Clancy a second year PhD student who taught us about greenhouse gas fluxes (CO2 and CH4) from grassland on peat soil. Next was Antonietta B. Knetge, a 2nd year PhD student who showed us plant fossilisation and diversity at South Tancrediakløft, Greenland, across the end-Triassic biotc crisis. The final talk of the day was from Catarina Barbosa, a 2nd year PhD student who told us about dominant and rare genera (groups of plant) in the same area as Antonietta’s study.

Day Two (Morning)

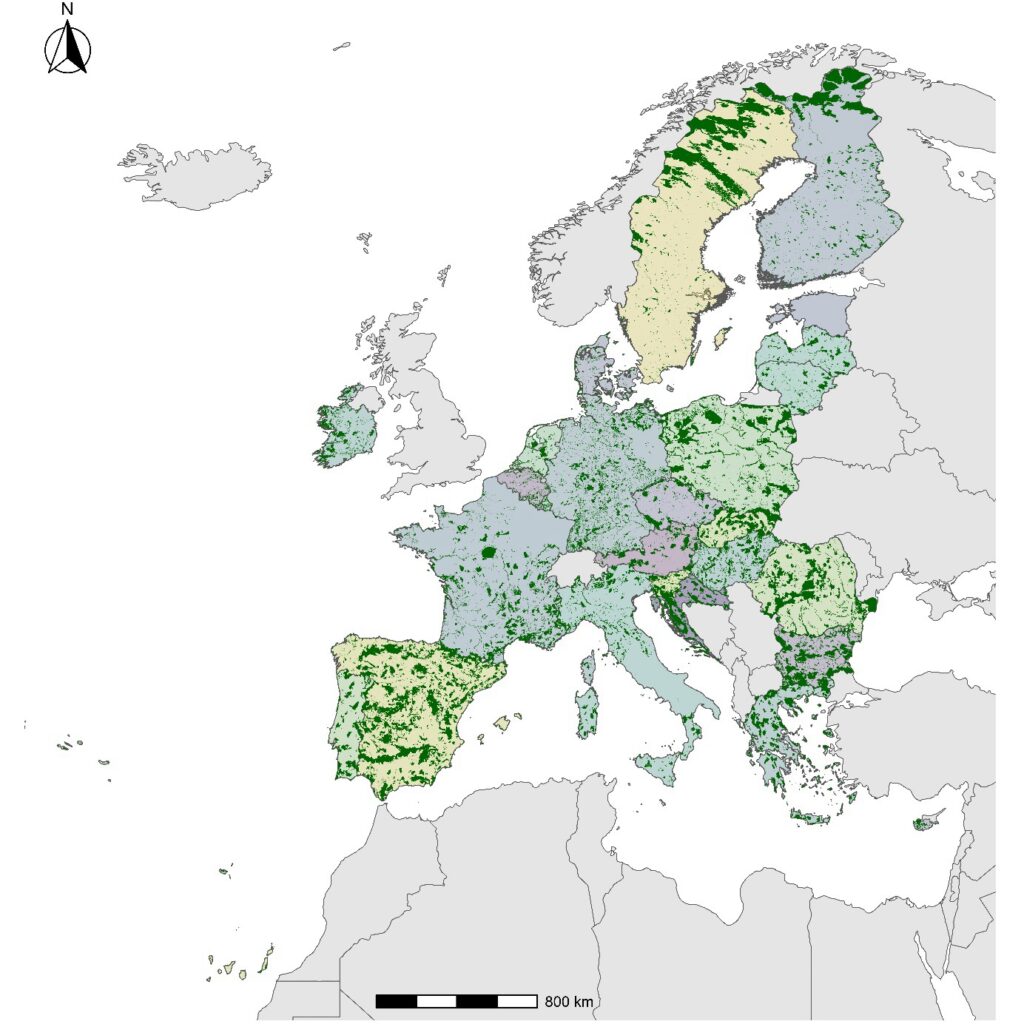

Day two started off with a talk by Kathleen Conroy a third year PhD student, who showed us how Bayesian Belief Network models can help land managers make decisions based on ecosystem services. Next, Simon Benson, a third year PhD student, talked about his work on identifying kelp functional traits in North Atlantic kelp species and their use in industry. After Simon, Aoife Molloy a Research Assistant showed us how to identify and assess best practice nature-based solutions for climate action in Ireland. Following Aoife, Josua Seitz a 2nd year PhD student talked about his work on modelling grassland turnover in the land surface model QUINCY.

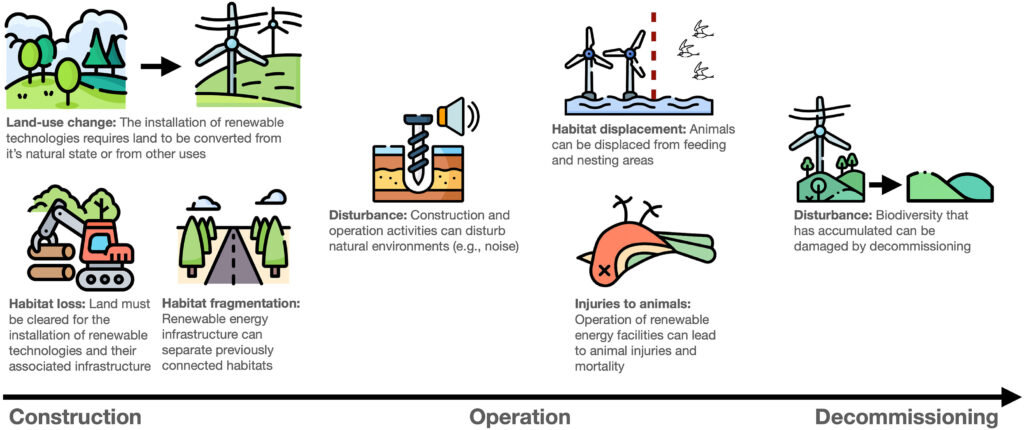

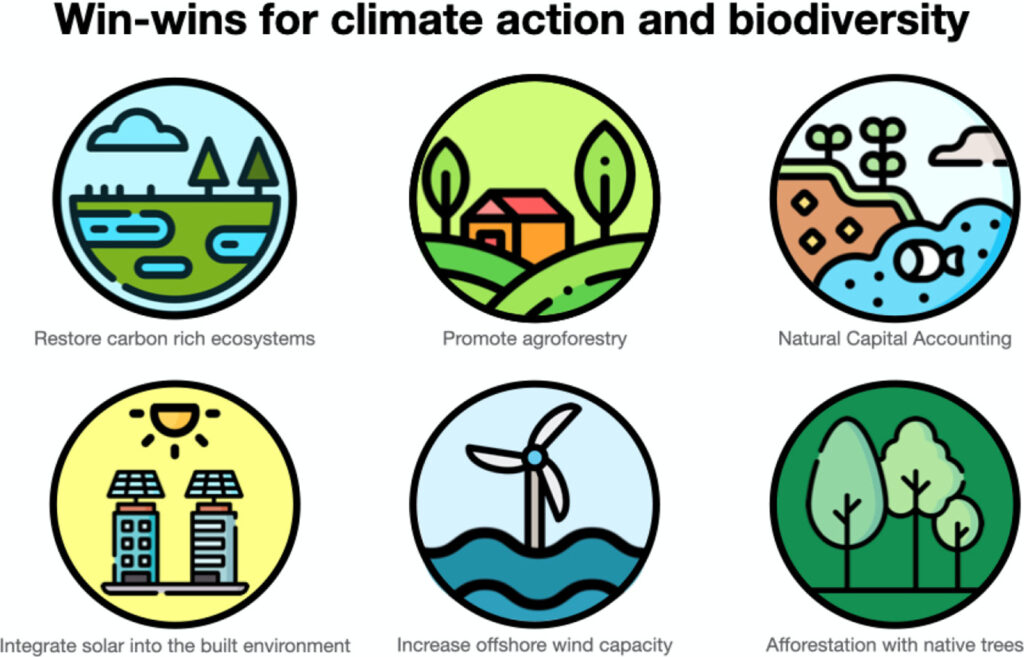

After a quick coffee break we jumped right back in with Charlotte Morgan, a second year PhD student who taught us about the threat of emerging herbicide resistance in Irish weeds. Next, Emma King a Research Assistant told us about using Natural Capital Accounting to identify how to manage wind farms to increase biodiversity. After Emma’s talk, we heard from Kate Harrington, a third year PhD student, who told us about factors driving the diversity and composition of floral and insect communities of young, native woodlands in Ireland. Next up was Vivienne Gao, a Research Assistant who showed us how polyphenolic content in seaweed, an important property for the food and pharmaceutical industry, varies with cultivation method and between species.

To finish off the session we heard from the post-doctorate Charlotte Carrier-Belleau who gave us an inspiration session about her journey so far. She began with how she began studying communication before realising science, and more specifically multiple stressors in the environment was her calling. This was followed by a Q&A with a panel of post-doctorates who gave great advice and honest answers to any curious people considering a post-doc.

Day Two (Afternoon)

After a delicious lunch the final session kicked off, we heard from MacDara Allison a 1st year PhD student who works on modelling plankton transport in Irish coastal areas using ocean current models. Next, Lauren Sliney, a Research Master’s student who showed us how studying tendon development in mice can help us uncover possibilities of tendon repair and regeneration in humans suffering from tendon and ligament damage. After Lauren, Whitney Parker, a third year student who discussed the varying host specificity and resistance between 200 Daphnia genotypes. The final postgraduate short talk was given by Moran Mirzaei, a first year PhD student who told us about using eddy covariance data to assess the impact of management practices on CO2 dynamics in Irish grasslands.

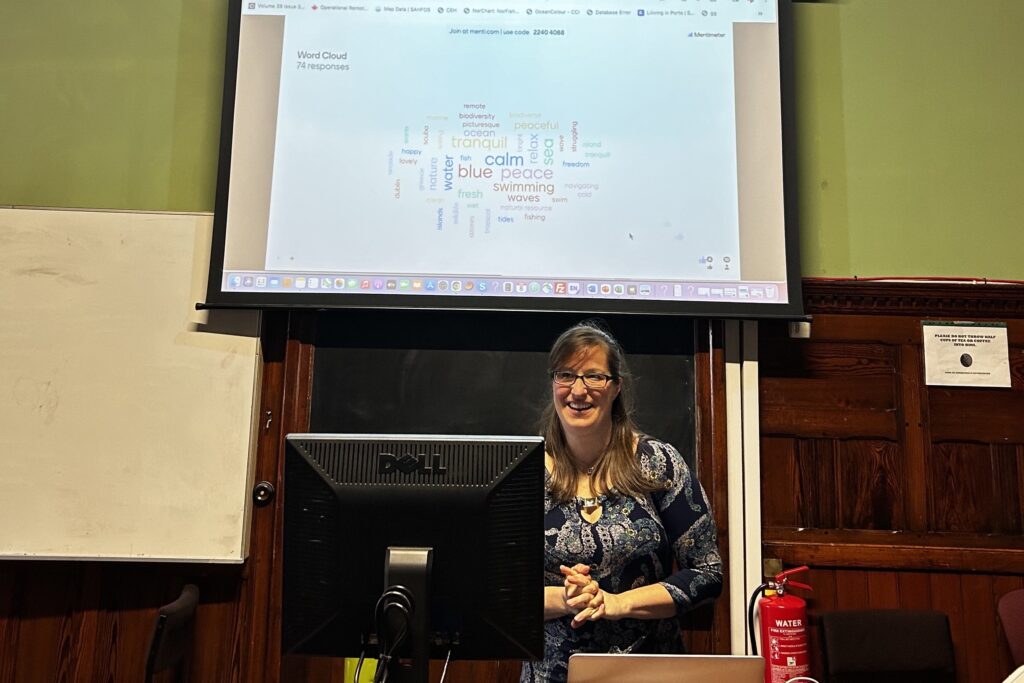

To end the day the second keynote speaker Dr. Cordula Sherer discussed how she had to learn a new perspective of working when she joined the humanities looking at marine ecology in history. One such project she recently worked on was adapting historical seafood recipes to the modern palette to encourage more seafood consumption and published “One Year of Irish Seafood: Traditional, Historical, Sustainable” while the recipes themselves are available on the Food Smart Dublin webpage.

The Winners

Finally, the winners for the talks were announced:

MacDara Allison won best 5-minute talk, Charlotte Morgan won best 10-minute talk, Emma King won best overall talk and Simon Benson won audience choice. Congratulations to them!

Until Next Year!

We want to say a huge thank you to the committee members for putting on such a friendly and supportive event! And congratulations to all the speakers, with a special mention to the winners again!

Finally, a quick reminder that if you have any EcoEvo news, research updates, or think pieces you’d like to write about, please get in touch. We’d love to hear from you and share your piece on the blog!