What is the first image that comes to mind when you think of evolution? Possibly a line of cartoon primates marching, slouching monkeys at one end and naked men with spears at the other. Or a branching tree diagram where each twig represents an organism, maybe with a tentative “I think” scribbled above it. Alternatively, you may have pictured an illustration of related birds from isolated islands, each showing a dramatically different bill shape adapted to a different diet. Darwin’s Galápagos finches represent a foundational influence in terms of where we tend to look for signs of evolution and what we expect these signs to look like. Our new paper, just published Open Access in Zoologischer Anzeiger: A Journal of Comparative Zoology, provides a contrasting image. We looked at the Sulawesi babbler (Pellorneum celebense), a dull brown bird that spends its time hiding in bushes on less isolated islands in Indonesia, looking pretty similar from one island to the next. Nevertheless, we found that several of its populations are quite different from one another in mitochondrial DNA, in morphology, and in song.

Continue reading “Evolution in the understorey”New Year, New Understanding of DNA

It’s the time of year for New Year’s resolutions and improving oneself. As a scientist, there are always about a million things to do to become a better researcher, but this year my resolution, and the one I hope all our readers adopt, is to become a better science communicator. Whether this means tweeting better links or publishing more frequently, the role of communication in science can’t be overstated. You don’t have to be a researcher to engage in scientific communication either, and it can be as simple as mentioning something you read or heard to a friend or family member. Continue reading “New Year, New Understanding of DNA”

Brown Bears and Shit Science

In my on-going attempt to improve myself I recently attended a lecture by Paul Eric Aspholm on brown bear tracking. This was a much more enjoyable and informative lecture than the last one attended and full of such interesting facts that I just had to share them!

Though the brown bear (Ursos arctos) is found throughout Eurasia and North America the talk focussed on those living in Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden, Finland) and Russia west of the Ural Mountains. In the first half of the 19th century Scandinavia implemented a cull with the intention of wiping bears out. This cull was halted in the 1930s and since then populations have rebounded. Much of the work by Mr Aspholm involved tracking bears to determine population size and movements across the region.

The focus of the talk was shit. Lots and lots of shit. Spring shit, which is mostly grass. Summer shit, which is mostly meat and bones (growing bears need calcium!) and autumn shit, which is mostly berries. The bears are so dextrous that they can pick and eat individual berries and can get through tens of kilos of blueberries in a day! Female bears are quite careful about where they defecate but the males are much more casual in their toilet habits, to the extent that they sometimes accidently walk in a previous bear’s deposit!

The shit is gathered by helpful hunters (who sometimes collect human shit by accident!) and is sequenced to obtain genetic information about the depositor which can be used to track individual bears. Other tracking methods involve collecting hair in hair traps (a line of barbed wire set in a square with a delicious – to bears – smelling lure in the middle) and collecting footprints in snow. This last method was the most innovative (to me, at least). Bears walking over snow will leave skin cells in their footprints. All the scientists have to do is collect a few footprints (around 5-7), melt the snow, get the cells and then sequence the DNA to get a complete genetic profile.

These methods enable researchers to track the habits of individual bears over many years and sometimes several countries. They have been able to show that the bear populations have rebounded well since the end of the cull, with around 8 females reproducing each year in Norway. The hope is to get that to around 15 females a year, still significantly lower than the estimated pre-cull population but a healthy size considering the amount of habitat currently available to them. Most surprisingly of all, the populations show no evidence of genetic bottlenecking or reduced even genetic diversity despite little movement between populations.

As a public service we were given some tips in case we ever come across a brown bear. The traditional advice is to sing. This is, surprisingly, true as it is a sound that only humans can really make. If you scream, you sound like a frightened animal and a perfect chance for a snack. If you shout, you sound like an aggressive animal looking for a fight and the bear is likely to oblige. We were advised not look into their eyes, and most importantly of all – don’t turn your back on it. This is apparently an invitation to play and bears play rough!!

It was an absolutely fascinating talk and I learned so much. Many thanks to Mr Aspholm for such an interesting lecture.

Author

Sarah Hearne: hearnes[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit

wikimedia commons

What is Life?

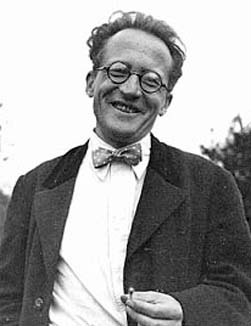

February 5th marked the 70th anniversary of the first lecture of what was later to become Schrödinger’s highly influential book ‘What is life’.

While Schrödinger may be more popularised by his infamous zombie cat, it was his thinking with regards to how life can live with the laws of physics that have allowed him to transcend that major divide between the physics and biological communities.

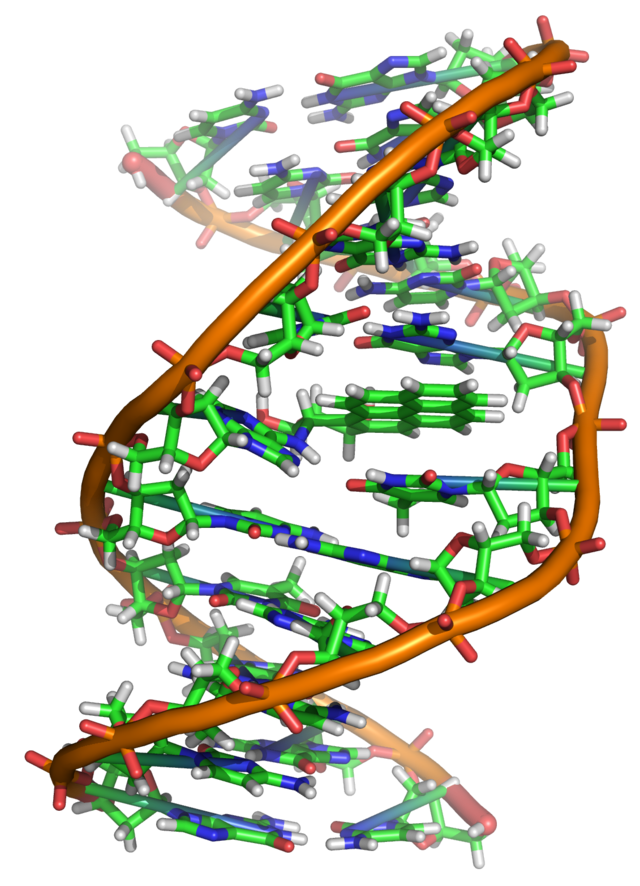

Schrödinger’s genius insight was to see life as a system behaving and constrained by the second law of thermodynamics, in particular describing the probable nature of a hereditary crystal, which would later lead scientists including Shannon and Weaver to the discovery of DNA and the genetic code.

However what makes the story of this work more fascinating, in particular to me as I have been lucky enough to get the opportunity to give a (very) small talk in the same lecture theatre were Schrödinger gave his lectures 70 years ago, is the story of how an Austrian physicist ended up in the capital of Ireland writing some of the most important work in biology of the last century.

Schrödinger, an Austrian, fled Germany in 1933 due to his dislike of the Nazi’s anti-Semitism and became a fellow in Oxford, during which time he received a Nobel Prize with Paul Dirac. However things turned sour with Oxford due to his less then monogamous approach to the opposite sex, and the lack of acceptance towards living with his wife and mistress lead him to leave for Princeton. These problems followed him there and eventual he found himself back in Austria in 1936. The occupation of Austria by the Germans in 1938 led him to again flee, this time to Italy. But in the same year Eamon de Valera, Ireland’s Taoiseach (Prime Minister) at the time, personally invited him to Dublin were he spent the next 17 years.

It was here in Trinity College Dublin that he delivered his lecture series which were to inspire both Watson and Crick to search for the genetic molecule and which has recently seen some increased popularity due to its use by Brian Cox in his latest series What is Life. However this work came about I like to think that “What is life” found its way to Ireland through Nazis and polygamy, a story surely of the calibre for the Discovery channel, if only it had some sharks.

Author

Kevin Healy: healyk[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit

wikimedia commons

Darwin’s insects, Dodo skeletons and macaques with braces

The Natural History museum in Dublin is one of my favourite places in the city. It has a very Victorian feel to it, none of this pandering to the X-box generation, just cabinet upon cabinet of mounted skins and skeletons revealing the diversity of nature. Some of the taxidermy is pretty hilarious and you can see the bullet holes in some of the skeletons, but that adds to the charm of the place!

I did a lot of museum based work during my PhD and absolutely loved using museum collections, so now I have my own students they all have museum collection aspects to their projects (whether they like it or not!). They will be using the collections in the Dublin museum, so today we had a tour behind the scenes of the museum, and a look at the storage areas with one of the curators Nigel Monaghan.

It was awesome! In the space of a few hours we saw insects collected by Darwin during his time on the HMS Beagle, a Dodo skeleton, a macaque skull with orthodontic braces (the original owner was apparently a dentist, though no-one is sure whether the macaque had braces in life or was just used for practice after it died), an entire room full of Irish elk crania and antlers, some wild Irish grass snakes (Ireland historically has no snakes of any kind), a DNA bank for every Cetacean stranded on the Irish coast, a huge selection of bird parts collected from birds that accidentally flew into lighthouses, and probably the funniest interpretation I’ve ever seen of what a guinea pig should look like.

As we went around, many of the things Nigel told us got me thinking about what an under used resource museum collections are. Certainly many people use the big collections in London, Paris, New York and Washington DC, but few of us would think to look in our local museums. For example, Nigel told us that a geneticist did a piece to camera in the museum recently and mentioned how wonderful it was that they had managed to extract Dodo DNA from a specimen in France. They seemed completely unaware of the fact that the Dublin museum has a beautiful Dodo skeleton in its collection. So my message is go out and use your local museum collections (or at least ask the curators if they have what you’re looking for)! They’re wonderful sources of information and inspiration, whether you’re a first year undergraduate student or a tenured professor. Right, now where did I put my calipers…

Author

Natalie Cooper: ncooper[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit

Natalie Cooper