Conference attendance can really impact your development as a Ph.D. student and give you great ideas for future collaboration and research. In March, I was lucky enough to attend the 2015 Benthic Ecology Meeting (or Benthics) in Quebec City, Canada. The Benthics meeting focuses on the ecology of the bottom layer of water systems, and this conference is mainly marine in focus. There were lots of great talks, one epic toboggan race, and nearly unlimited opportunities for networking and discussion. A quick overview of my three favourite talks is below. Check out what you missed and hope to see you in Maine next year! Continue reading “Everything’s Better Down Where It’s Wetter: Benthic Ecology Meeting 2015”

Pint of Science Ireland

This May, 80 of Ireland’s leading scientists will bring their research to 8 pubs in 3 cities for 3 fun-filled nights of science! Part of the international festival, Pint of Science Ireland takes science out of the lab and mixes it into some of the most interesting, engaging and unusual evenings you will ever spend in a pub.

Whether you’re a researcher, student or science-newbie, the festival is a great opportunity to hear about the latest scientific research and chat with Ireland’s top scientists over a pint. Running in Galway, Limerick and Dublin from the 18th to 20th of May, come along to one of the 8 venues for fascinating talks within the themes of the beautiful mind (with an added bonus from illusionist Rua), the human body, technology and the physics of atoms to galaxies. Tickets are free but some evenings are already booked out so hurry to get your place!

Find out more on the Pint of Science website (www.pintofscience.ie) and follow @pintofscienceIE on twitter for all of the latest science shenanigans!

Author: Sive Finlay, @SiveFinlay

Academic challenge

Bright Club is a variety night of entertainment combining light-hearted research talks from academics and performances from professional comedians. It has been running for several years now across various venues around the UK and recently made the leap to Dublin. Off the back of some grade-A flattery that pandered perfectly to my ego, I agreed to get involved as an academic for the April show. Although being comfortable with lecturing and presenting my science, I have no experience in comedy, or even drama for that matter, so this was a huge step outside my comfort zone. Thankfully, some helpful training from Niamh Shaw in the week beforehand showed me how entertaining starts with being comfortable with yourself in front of an audience. It was a great evening packed with songs, linguistics, one-liners, neuroscience, wit and visualisation.

This was a humbling experience. I think I managed ok with a story about intelligence, cooperation and “devious f***er” politicians, but I learned a huge amount. I learned that narrating a short coherent story without the aid of slides, or props to prompt you is really, really difficult. You have nothing to hide behind: all eyes are on you. You have nothing to jog your memory of your story. You can just stand up there and wing-it safe in the knowledge that you can just talk to each slide as it appears.

This is something that we as academics should challenge ourselves to do: give a talk (not necessarily a comedic one) that lasts 5 to 10 minutes on your research without any notes, slides, prompts or props. It will make you realise just how skilled stand-up comedians are, and how it’s a very different skill to be an entertaining speaker rather than an entertaining lecturer. Of course our job is to be an entertaining lecturer, but there is a lot to learn from the fear and loneliness of standing up in front of a crowd that is hanging on your every word and action. One way to do this would be to get in touch with Bright Club and sign yourself up for an event near you!

Author: Andrew Jackson @yodacomplex

Photo credit: Bright Club

Mixed Messages, Pesticide Pestilence and Pollinator Populations

“We’re getting mixed messages from scientists about the effects of neonicotinoids on bees” – I have heard this from several sources, including a very senior civil servant in the UK and from an intensive tillage farmer in Ireland. A recent article in the US media says pretty much the same thing. An article in the Guardian last week entitled “UK drew wrong conclusion from its neonicotinoids study, scientist says”, reports on Dave Goulson’s reanalysis of the Food & Environment Research Agency (FERA)’s own data, but draws the opposite conclusion.

So why is there confusion on bee decline and the role of neonicotinoids? I believe it’s down to several factors:

1. “Bees” are a diverse taxonomic group of insects, including the well-known eusocial honeybee Apis mellifera, the familiar bumblebees in the genus Bombus, plus hundreds of other species of bee, which have quite different life histories and ecologies, most of which do not form social colonies. When talking about bees, we need to be clear about which ones we are discussing. If everyone is clear about which taxonomic group they are talking about, this could cut down considerably on the confusion. (By the way, the Guardian used a picture of honeybees as the image accompanying their article on bumblebees).

2. Honeybees are managed by beekeepers. If a colony dies out (especially over winter in temperate countries), it is replaced by splitting a strong colony in spring. If the colony is sick, it is treated. When we talk about honeybee decline, we are either referring to colony losses (i.e. colonies dying out, which can be caused by a range of factors, especially parasites and diseases, and is highly spatio-temporally variable); OR we are referring to the fact that there are fewer beekeepers out there, or that each one is keeping fewer colonies. The point is, when colonies die out, beekeepers can restock and the total number of honeybee colonies depends on the activity of beekeepers. This is why there appears to be no decline in honeybees in the US. This is not the case for wild bees.

3. Eusocial bees, by the very nature of their colonial societies, are to some extent buffered against environmental stochasticity and pressures. If a few hundred honeybees are killed whilst out of the hive foraging during the summer, it may have little impact on the colony, because there are 50,000 or more honeybees left in the hive. This may be a reason why lab-based findings cannot always be scaled up when replicated at field level. Measuring effects at the colony-level is also another problem. A range of different experimental approaches has led to mixed conclusions on the effects of neonicotinoids on honeybees.

4. A huge number of independent peer-reviewed studies have shown negative lethal and sub-lethal effects of neonicotinoids on wild bees and other non-target organisms (e.g. see review by Pisa et al. 2015), in laboratory, and semi-field studies. Realistic field-level studies on the other hand are challenging methodologically: some bees have large foraging ranges and so studies must be conducted over large areas; pesticide free “control” sites are very hard to find; and wild bees are subject to a range of interacting pressures (loss of forage resources, parasites and disease, cocktails of pesticides, use of managed bees for pollination purposes, climate change…), and disentangling the effects of these pressures in a field experiment is hard. However, those few studies that have been conducted properly appear to support the lab and semi-field findings.

5. The media band-wagon… When the media polarise environmental issues, it’s very hard for people to make an informed decision – instead of crediting the general public with the intelligence to understand that the environment is highly variable in both space and time, and that ecological systems and interactions within them are highly complex, issues are presented as cut-and-dried in one direction or another. Thus the confusion is maintained, so that the next big news story, that contradicts the previous one, can have a bigger impact.

There shouldn’t be any confusion – neonicotinoids have sufficient negative impacts on non-target organisms for us to be concerned about their widespread and often prophylactic use (e.g. as seed dressings). We should also worry about the wider environmental impacts of pesticides like neonicotinoids – how persistent they are, how they get into the soil and water-courses and affect other organisms that provide essential ecosystem services. And we shouldn’t just be concerned about neonicotinoids – the massive cocktail of chemicals we intentionally and accidentally unleash on the natural environment could have long-term and very damaging effects to our natural capital. Including bees.

Author: Jane Stout, stoutj[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit: wikimedia commons

Is the medium a monster?

“Dinosaurs have become boring. They’re a cliché. They’re overexposed” – Stephen Jay Gould

“Dinosaurs have become boring. They’re a cliché. They’re overexposed” – Stephen Jay Gould

Dinosaurs have always been inextricably linked to popular culture. Despite going extinct 65 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period they pervade our society. Dinosaur exhibits are the main attractions of natural history museums and outside of this setting, they can be found in films, documentaries, books, toy shops etc. A new discovery of one of these animals frequently adorns our newspapers. Even the word dinosaur has entered our everyday language as a metaphor to describe something as hopelessly outdated. Because of this pervasiveness there seems to be an implicit assumption among science communicators that dinosaurs “sugar-coat the pill of knowledge” but I’ve often wondered about the exact role these animals play in helping scientists communicate their subject. Perhaps they’re viewed by the public as little more than monsters, no more educational than dragons or the abominable snowman.

The well known science populariser and palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote an article about the nature of ‘Dinomania’ for the New York Review of Books around the time of the release of the film version of Jurassic Park. His article is wide ranging, exploring how dinosaurs have become so popular and asking if the excitement surrounding them at that time was just a fad; the result of cynical commercialisation. The most pertinent point he raises is the effect that such commercialisation has had on science communication efforts, “ In the past decade, nearly every major or minor natural history museum has succumbed (not always unwisely) to two great commercial temptations: to sell many scientifically worthless, and often frivolous, or even degrading, dinosaur products in their gift shops; and to mount, at high and separate admissions charges, special exhibits of colorful robotic dinosaurs that move and growl but (so far as I have ever been able to judge) teach nothing of scientific value about these animals.” He concedes that such animatronics would be useful if they were integrated with other educational exhibits but bemoans the fact that they are often separated from the rest of the exhibit entirely.

A further point he raises is that of the antagonistic relationship that has resulted from ‘dinomania’. He explains how, “Dinomania dramatizes a conflict between institutions with disparate purposes—museums and theme parks. Museums exist to display authentic objects of nature and culture—yes, they must teach; and yes, they may certainly include all manner of computer graphics and other virtual displays to aid in this worthy effort; but they must remain wed to authenticity”.

But if we look at the history of dinosaurs they ‘escaped’ into the public sphere almost as soon as they were discovered. They were never contained solely within the purview of science and scientists. The Victorian anatomist Richard Owen who gave dinosaurs their name collaborated with the artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins in creating the first models of these animals. The Great Exhibition of London at Crystal Palace in 1854 displayed these sculptures to the public who were astounded. Pictures, posters and replicas of the sculptures were made available to the public. Certainly, commercialisation was no recent addition.

And 22 years after the release of Jurassic Park dinosaurs are still as prominent as ever, so it seems ‘dinomania’ was no flash in the pan. My own view is that these animals are an excellent means of showing the wonder of science and nature to people, often acting as a gateway to science especially among children. Yes they may be cynically marketed and there are many inaccurate representations of dinosaurs but undoubtedly even these have evolved. The Tyrannosaurus of Jurassic Park is a much more accurate representation of the animal than the version who fought King Kong 60 years earlier. It appears that dinosaurs are well-placed to both educate and entertain with neither component mutually exclusive. The final words go to palaeontologist Bob Bakker:

“Interest in dinosaurs is not a fad. Dinosaurs are nature’s special effects, extraordinary monsters that were created not by a Hollywood computer-animation shop but by the natural forces of evolution.”

Author: Adam Kane, kanead[at]tcd.ie, @P1zPalu

Photo credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jurassic_Park_%28film%29#/media/File:Jurassic_Park_poster.jpg

War of the Words – The Conflict between Science and Journalism, Part 2

In a previous post I outlined some potential areas of conflict between scientists and the journalists who are reporting on research. Here I want to continue my look at this relationship. First off let’s start by looking at some surprising results from the social science literature which show that more often than not scientific findings are accurately reported.

In a previous post I outlined some potential areas of conflict between scientists and the journalists who are reporting on research. Here I want to continue my look at this relationship. First off let’s start by looking at some surprising results from the social science literature which show that more often than not scientific findings are accurately reported.

One study by Peters et al. (2008) reported, “interactions between scientists and journalists are more frequent and smooth than previously thought.” Another study, this time of science coverage in the Italian press, found that “There is almost invariable agreement between the author of the article and the sources” (Bucchi and Mazzolini 2003). The authors of the latter paper go on to state that, “This predominantly positive tone of science coverage, documented also by other studies of the daily press, is again in contrast with many critical stereotypes and contributions.”

There is a paradox apparent in all of this. How is it that the majority of scientists are happy with the journalistic interpretation of their studies and yet journalists are portrayed as constantly reporting the science inaccurately? Celeste Condit (2004) reports that “It was all too natural for critics [of the media] to notice and reprint examples of egregious reporting, portraying these as typical of the rapidly burgeoning area of genetics reporting.”

We should be aware that the general claim from scientists that journalists simplify scientific data could be levelled at scientists themselves. The final Nature paper tells a story without mention of any bumps on the road. Peter Medawar recognised as much when he asked “is the scientific paper a fraud?” Of course every scientific paper cuts out the difficulties encountered and smooths the rough edges.

This seems to be the answer to the question of conflict; a select few examples of sloppy journalism are used to criticise science journalism as a whole. It appears to be the case that many of the criticisms of science journalists are unwarranted.

But is this relationship something we should want? I would argue that it may not be entirely beneficial. Of course it is important that scientific work isn’t misrepresented and that there are many findings of science that ought to be celebrated but a critical article on some body of research may often be justified. As Phillip Ball says, “Making scientists happy is not the aim of science journalism…” Murcott (2009) believes science journalists’ dependence on sources makes them different to other journalists. “You could say that this is not exactly a description of a journalist — more that of a priest, taking information from a source of authority and communicating it to the congregation.” I would agree with this point and his conclusions that “The ‘priesthood’ model of science journalism needs to be toppled.”

Of course there are problems if this model is to change because as he points out “The time pressures on journalists today do not bode well for calls for more depth, context and criticism” (Murcott 2009). Colin Macilwain (2010) echoes these views and says “Scientists and the media are trapped in a cosy relationship that benefits neither. They should challenge each other more.” Naturally, researchers do not want “to be held to account by the press.” Macilwain advocates more dedicated journalistic coverage that criticises science in a way that other journalistic beats do. “Reporters and editors could then engage with sets of findings and associated issues of real societal importance in the news pages, asking the hard questions about money, influence and human frailty that much of today’s science journalism sadly ignores”.

One trend that is likely to increase conflict is the decline in the number of specialised science reporters. PZ Myers, a scientist and active blogger says “the problem with science journalism…is that too often newspapers think you don’t need a science journalist to write it. Any ol’ hack will do.” (Myers 2010). I would contend that as newspapers assign non-specialist reporters to their science beat the number of instances of bias, misrepresentation, inaccuracies etc. will rise.

It should be noted that scientists have a role to play in this too. If specialised science reporters disappear scientists will have to recognise this and be sympathetic if and when they deal with a journalist who is relatively ignorant of the science. In this way there will be less room for inaccuracy and misrepresentation. I would agree with the conclusions of a piece in the journal Nature that scientists by working with journalists can “ensure that journalism programmes include some grounding in what science is, and how the process of experiment, review and publication actually works” (Nature 2009).

The current relationship that science journalists have with their sources means that, although there is room for conflict, it is far from inevitable. Indeed, it seems that Colin Macilwain’s concept of a “cosy relationship” is a more accurate representation. In conclusion I would suggest that there are two forms of conflict that can occur between science journalists and their sources. There is the ‘watchdog approach’ whereby journalists are skeptical of their sources, investigate their motives and question their research. This, I would argue, is something that society should have even if it generates some friction between journalist and source. The second area of conflict is that which occurs when journalists misrepresent, misquote and inaccurately report the science. This, of course, is not something anyone wants.

Author: Adam Kane, kanead[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit: http://gloucesterconcordes.ca/welcome/extra-extra-read-all-about-it/

References

Anderson, A Peterson, A David, M. (2005). Communication or spin? Source-media relations in science journalism. In, Allan, S Journalism, critical issues. England, Open University Press. p. 188-198.

Ball, P. (2008). When reporters attack. Nature. 321, p.204-205.

Bubela, T Caulfield, T. (2004). Do the print media “hype” genetic research? A comparison of newspaper stories and peer-reviewed research papers. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 170 (9), p. 1399-1407.

Bucchi, M. Mazzolini, R. G. (2003). Big science, little news, science coverage in the Italian daily press, 1946–1997. Public Understanding of Science. 12. p. 7-24.

Condit, C. (2004). Science reporting to the public, Does the message get twisted? Canadian Medical Association Journal. 170 (9), p. 1415-1416.

Conrad, P. (1999). Uses of expertise, sources, quotes, and voice in the reporting of genetics in the news. Public Understanding of Science. 8, 285-302.

Dickson, D. (2005). The case for a ‘deficit model’ of science communication. Available, http,//www.scidev.net/en/editorials/the-case-for-a-deficit-model-of-science-communic.html.

Goldacre, B. (2005). Don’t dumb me down. Available, http,//www.guardian.co.uk/science/2005/sep/08/badscience.research.

Hansen, A. (1994). Journalistic practices and science reporting in the British press. Public Understanding of Science. 3, 111-134.

Ipsos MORI. (2009). Doctors Remain Most Trusted Profession. Available, http,//www.ipsos-mori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/poll.aspx?oItemId=2478.

Macilwain, C. (2010). Calling science to account. Nature. 463, p. 875.

Medawar, P. (1964). ‘Is the scientific paper a fraud?’ Available, http,//contanatura-hemeroteca.weblog.com.pt/arquivo/medawar_paper_fraud.pdf.

Murcott, T. (2009). Science journalism, Toppling the priesthood. Nature. 459 (7250), p. 1054-1055.

Myers, P.Z. (2010). The problem with science journalism…. Available, http,//scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/2010/03/the_problem_with_science_journ.php.

Nature. (2009). Cheerleader or watchdog? Nature. 459 (7250), p. 1033.

Nelkin, D. (1996) Medicine and the media, An uneasy relationship, the tensions between medicine and the media. The Lancet. 347 (9015). p. 1-10.

Peters, H.,P. Brossard, D. de Cheveigné, S. Dunwoody, S. Kallfass ,M. Miller, S. Tsuchida, S. (2008). Interactions with the Mass Media. Science. 321 (5886), p.204-205.

Radio skills for scientists

The Irish Academy of Public Relations recently hosted a free event, “Radio Skills – A Special Evening for the Science Community” at the FOCAS Research Institute in DIT. The points raised and ensuing discussions provided interesting insights into relationships between scientists and journalists.

Ellen Gunning, director of the Academy, chaired the evening. From her experience of teaching public relations and interview skills, she described how many scientists are like Guards (the police) in how they deal with the media. Both professions are trained to communicate in a very impartial, specific and direct way with an unhealthy dollop of jargon. However, the key to effective public communication is to cut the jargon and to identify a clear, straightforward message which will be interesting and understandable for non-specialist audiences.

Professor Hugh Byrne gave a scientist’s perspective of dealing with the media. He highlighted the increasing importance of public engagement and research dissemination beyond the ivory tower of academia. Researchers must engage with the media to create a sustainable scientific research culture in which scientists are accountable for how they spend tax payers’ money.

He also discussed the “dark side” of engaging with the media. Many scientists are wary of journalists because they are afraid of being misquoted or that their research will be sensationalised. The immediacy of a live radio interview is a scary prospect for scientists who are used to careful drafting and re-drafting of their words for academic publications. As Professor Byrne pointed out, many scientists are used to building their arguments backwards: weaving different strands of argument together to finally reach the main conclusion or take home message at the end. Journalists want the opposite: the hook for why your research is interesting or important needs to come first.

However, scientists need to get over their fear engaging with the media. Good journalists are not trying to catch you out: they want to get their facts right just as much as you don’t want to be misquoted. Good science communication stems from a feeling of trust and complicity between the scientist and journalist.

Sean Duke continued the discussion with a journalist’s perspective of working with scientists. He further underlined the importance of building good relationships and trust with researchers. He pointed out that, despite their concerns, scientists have more control of a news story or interview than journalists. Researchers are the experts in their own field, they are the ones who dictate the parameters of a story so it’s up to scientists to find the interesting nuggets of information or take home messages. To do this effectively, it’s a good idea to follow Duke’s checklist for how to deal with journalists.

Journalists want:

A good story: find a way to give it to them by explaining your science through reference to everyday life. What’s interesting about your research and why should people care?

Explanation, not patronisation: scientists need to explain their research clearly so that it’s understandable for a non-specialist audience but don’t slip into “dumbing down” your story.

Scientists who take control: remember that you’re the expert so you should lead the story. If you’re contacted by a researcher for a radio show then treat it as an audition for the live interview. Have an agenda for what you want to communicate, it’s up to you to dictate and take control of the story.

Journalists don’t want:

Jargon: scientists are brainwashed to use complex terms that might as well be a foreign language to most audiences. Think of yourself as a translator: don’t use acronyms or obscure terms that will alienate and confuse your audience.

Defensive interviews: treat an interview with a journalist as an opportunity, not a penance. Good journalists are not trying to catch you out but neither should you expect them to know every detail about your research field. If you are asked what you think is a strange or misguided question, give the journalist the benefit of the doubt instead of becoming defensive about your position.

To be lectured: scientists are used to giving lectures or presenting at conferences. These formal settings are very different to the informal, conversational style of most interviews. Don’t complicate an interview by slipping into lectorial mode.

The Irish Academy will explore some of these topics further and provide more in-depth radio and PR training for scientists during their one day training course, “Radio Interview Skills for Scientists” on the 11th of April. Places on the course are limited to six people and can be booked here. Details of the Academy’s other courses can be found on www.irishacademy.com.

Author: Sive Finlay, @SiveFinlay

Photo credit:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/primaryhistory/world_war2/daily_life/

The importance of being Earnest – The case of climate change

In Oscar Wilde’s comedy “The Importance of Being Earnest”, Cecily and Gwendolen want to marry a man named Ernest simply because of the name’s connotations. They are so fixated on the name that they would not consider marrying a man who was not named Ernest. The name, sounding like “earnest”, shows uprightness, inspires “absolute confidence”, implies that its bearer truly is honest and responsible.

A name can truly be very important when it embodies the communication of a message. Surprisingly (or not) it is also important when dealing with international treaties and initiatives. An example is the story of the Ozone Hole and the Montreal Protocol, the most successful governmental agreement on an environmental problem at the global scale. The Montreal Protocol, signed in 1987 by 46 countries (now having nearly 200 signatories), banned the use and production of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) worldwide, recognizing that they represented a threat for the stratospheric ozone layer. During the celebrations for the 25th anniversary of the Protocol, Jonathan Shanklin, Head of Meteorology and Ozone Monitoring Unit for the British Antarctic Survey declared that in retrospect, the Ozone Hole was a really good thing to call the ozone depletion problem “because an Ozone Hole must be bad. Almost automatically, it meant that people wanted something doing about it. The hole had to be filled in”.

Much more confusion is involved in naming another problem at the same global scale: global warming, or climate change. The international agreement on it, the Kyoto Protocol, is not being as successful as the Montreal one.

“Global warming” and “Climate change” are two different phenomena, casually related. “Global warming” refers to the observation of a long-term trend of increasing temperatures. “Climate change” refers to different changes in climate phenomena driven by the increasing concentration of greenhouse-gases in the atmosphere. The alternative use of the two “names” probably contributed to the misunderstanding of the problem for the general public, giving alibis to those who are (conveniently) sceptical about climate change. That happens for example whenever a winter is colder than the year before, or more snowy, then “where is the global warming?”.

Surely the fact that the Montreal Protocol was successful and Kyoto Protocol is not, has much more profound and complex reasons than just the “naming”. There is however a trade-off between scientific rigour and effective communication to deal with. Scientific rigour should guide our management plans, effective communication should stimulate actions.

The scientific community and political stakeholders have to be “earnest” in balancing rigour and communication strength.

Author

Luca Coscieme, coscieml[at]tcd.ie

War of the Words – The Conflict between Science and Journalism, Part 1

Science journalists have a vital role to play in modern society, typically acting as gatekeepers of scientific knowledge for the public. According to the sociologist Peter Conrad (1999), “Science journalism is an increasingly important wellspring of public understanding of science.” Science journalists are an interesting subset of journalists in that they depend on press releases of areas of scientific research for their stories. The broadcaster Toby Murcott (2009) says that science journalism has a “rhythm” that tracks the publication of notable science journals like Science and Nature. “As press releases describing research arrive in our inboxes they are scanned for stories, the most newsworthy picked, offered to editors and then reported.” However journalists do not simply abridge a research paper; they typically contact expert sources to add to their stories. In this role science journalists use experts for a number of reasons. An authority can explain a finding and its implications both positive and negative. Moreover, quoting an expert can add credence to a story and give balance (Conrad 1999). According to Anders Hansen (1994) “[b]ecause of the complexity of much science, science journalists are seen as being uniquely dependent on the co-operation of their sources”. He adds that it is essential that there is a “relationship of trust” between the two. But does such a relationship hold? Or are science journalists and their sources in a state of conflict?

Differences of opinion

Clearly, science journalists are journalists first and specialists second whereas scientists are obviously science focused. This difference does not necessitate conflict but it permits it. One can conceive of a number of reasons that could foster disharmony between journalists and their scientific sources.

David Dickson (2005) expounds on these purported problem areas when he bemoans the latest trends in science reporting saying, “Sadly, we are currently witnessing a worrying trend within much of the world’s media, where a traditional commitment to reporting facts is giving way … to a more colourful, but less reliable, tendency to concentrate coverage on interpretations of fact (or ‘spin’).” He contends that the main problem with journalism in this respect is more to do with inaccurate reporting of the facts than bias. Bucchi and Mazzolini (2003) state that “The media are blamed for…allocating inadequate space to scientific topics, their inaccuracy in reporting about the issues, and exaggerating the political or non-scientific significance—indulging in dramatization and sensationalism.”

Another issue is that the conclusions science draws are never final, rather there are different levels of confidence assigned to theories. But uncertainties and probabilities with assigned statistical likelihoods do not make good stories from a journalistic perspective. So-called news values are not always applicable to scientific progress. Take timeliness for instance. Rarely is a scientific discovery an instantaneous thing, instead there is a lengthy progression from initial observations to final conclusions. So journalists are actually reporting on the publication of a journal paper.

In addition to news values Dorothy Nelkin (1996) points out that the different ways journalists and scientists use language can lead to conflict. She argues that “Certain words routinely used by scientists have different meanings for lay readers. Scientists use the work “epidemic” to describe a cluster of health-related incidents greater than expected; to a lay person, an epidemic implies a rampantly spreading disease.” She also points out simplifications that a journalist will draw on. For example they “will refer to the “fat gene” rather than to the “marker that may predispose an individual to obesity”.” The reason for this different use of language is that journalists use words for “graphic appeal” in contrast to frank, specialised scientific writing.

She goes on to contend that one of the most important areas of conflict arises from the different opinions scientists and journalists have about the role of the media. Scientists see the press as means to transmit information about their research to the public in an accessible way. Science journalism, in their view should popularise science and “convey a positive image”. According to Nelkin “they are reluctant to tolerate independent analysis of the limits or flaws of science, or the relative costs or benefits of new technologies.” This, in her view, is in contrast with journalists, “who do not see themselves as trumpets for science, [with] many … beginning to suspect promotional hype.” Nevertheless I do not think that scientists are entirely wrong with their view of science journalism. There is still an element of ‘Gee Whiz’ about science stories in my view. Indeed, I think a case could be made that many reporters do act as “trumpets for science.”

There also seems to be an inherent distrust of journalists by some scientists. Medical Doctor and blogger Ben Goldacre writes of media science coverage, “It is my hypothesis that in their choice of stories, and the way they cover them, the media create a parody of science, for their own means. They then attack this parody as if they were critiquing science.” Goldacre (2005) groups science stories into three categories wacky stories, scare stories and breakthrough stories. These categories nicely align themselves to the news values of unexpectedness, negativity and threshold.

The idea that there are two sides to every story can be a dangerous one when it comes to science writing. There are some instances where the science is well-founded yet journalists will quote a minor yet vociferous opposition. It seems likely to me that the main author of the study will be irked if his research is countered by somebody who has a bone to pick or is just manifestly wrong. This is all too common in the area of climate change. This point is raised by Nelkin (1996) who writes, “The norms of objectivity in journalism call for giving “equal time” to different points of view—for balancing conflicting claims. This is a source of irritation to scientists, because scientific standards of objectivity require not balance or equal time but empirical verification of opposing hypotheses.”

Next time out I’ll discuss some research that shows most scientists are quite happy with how their work is portrayed in the media as well as critiquing the relationship that has developed between journalists and scientists.

Author: Adam Kane, kanead[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit: http://www.saltburnschool.co.uk/2012/07/press-call/

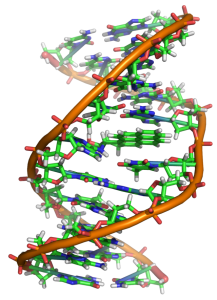

New Year, New Understanding of DNA

It’s the time of year for New Year’s resolutions and improving oneself. As a scientist, there are always about a million things to do to become a better researcher, but this year my resolution, and the one I hope all our readers adopt, is to become a better science communicator. Whether this means tweeting better links or publishing more frequently, the role of communication in science can’t be overstated. You don’t have to be a researcher to engage in scientific communication either, and it can be as simple as mentioning something you read or heard to a friend or family member. Continue reading “New Year, New Understanding of DNA”