A few months ago in our weekly NERD club we ran a session on dealing with stress. Part of this session revolved around what made us stressed, and one of the big problems was feeling like we had too much to do and too little time to do it. To follow up on this, this week we looked at how to be more productive. Many of our discussions revolved around the ideas presented here and here.

What makes us less productive?

The causes of our lack of productivity varied across career stages and the types of work we were involved with. Almost everyone had one major problem – the internet. Postdocs and PIs complained about the huge volume of emails and the desire to deal with them. PhD students weren’t so distracted by emails, instead their issue tended to be things like news websites. All of us have problems with distractions like social media, cute animal pictures and xkcd. Solutions included strictly restricting time doing these things, and/or the number of links you are “allowed” to click and explore before going back to work!

Another big issue was other people. This included supervisors/collaborators who won’t respond to emails or always delay or cut short meetings, suppliers messing up equipment orders, arcane university policies requiring endless form filling, constant interruptions from students etc. This is probably impossible to solve, but did provoke an interesting debate – what if your productivity actually reduces the productivity of someone else? For example, many of us had examples of people who would delay replying to emails until it was convenient for them but this would severely delay someone else working on the project. Another common complaint was people who call you to ask questions – this is great for them as they get an immediate answer but often frustrating for the person who has been interrupted. The only solution we could think of was a) talk to the person involved and calmly explain the problem to see if it can be solved and b) to all think carefully about how our actions affect others (of course I’d like to think we all do this anyway but I know we don’t!)

Finally, we discussed how these distractions all become worse when you have something you really don’t want to do (for me this is grading!). You will do literally anything other than that task. Again this is hard to solve, as it requires self-discipline (and for many people it requires the sound of the deadline whooshing by). My solution has been to work out a really short amount of time that I think I can cope with doing that task for. I then set a timer and do it for that long, or often longer as these things are rarely that bad once you get over the initial hurdle of starting. I then reward myself with a break. I find this works even better if you can do it with a colleague. Yes, it takes far longer to get the task done than it should, but it does get done rather than sitting on your desk and giving you the side-eye all day/week/month.

Unique snowflakes of productivity

An important thing to note throughout these tips is that different things work for different people! I find working at home great for my productivity, others find they spend the whole day tidying the house. I work best in the evenings, other people work best at 6am. Do whatever works for you!

Potential solutions

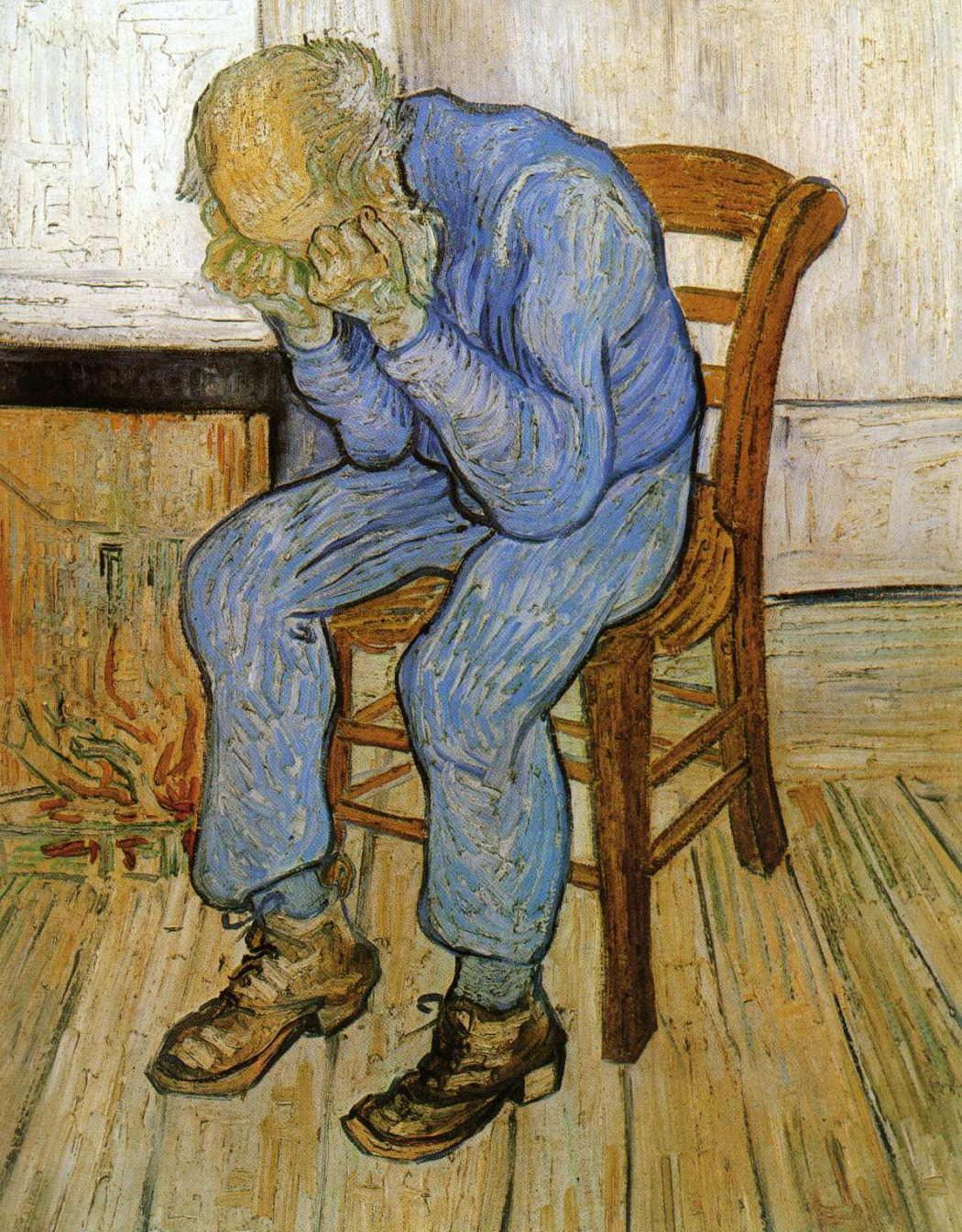

- Be kind to yourself

I think this is most important, especially in light of the stress discussions we had earlier in the year. Most of us are more productive when we eat well, get plenty of sleep, exercise regularly and work sensible hours. Yes, you will get a lot of stuff done if you work crazy hours for a couple of weeks. But that increase in productivity comes at a price of burn out, getting sick or generally losing motivation for the project. Working a 35 hour week has been shown to be most effective for prolonged productivity. Taking breaks is also really important.

- Redefine and monitor your productivity

Sometimes our frustrations with how we are doing are related to what we think counts as productivity. We might set goals that are too high, or forget about all the little things we achieved during the day. A suggestion was to make a thorough to-do list (I use trello.com to keep my to-do list synced across multiple computers and because you still get the satisfaction of ticking stuff off!). Making the list is also a useful procrastination activity (see below)! It does make me feel weirdly better when I see small tasks being ticked off, even if the larger whole of the task is yet to be completed.

- Find out where your time is going

Another common complaint was coming into work, seemingly working hard all day, but then having nothing to show for it. One suggestion from @DRobcito was to try keeping a “time diary” for a couple of weeks. This involves just noting down somewhere what you’ve done and how long it took you to do it. Although annoying to do, this is a great way to see where your time is going, what you should be spending less time on, and what kinds of activities you might want to say no to in future because the time expended doesn’t match the benefits.

- To Pomodoro or not to Pomodoro

A lot of articles on this subject recommend the Pomodoro technique where you work for 25 minutes, take a short break, then work another 25 minutes. After four or five repeats you take a longer break. Most of us had tried this, or a version of it, and most of us found it didn’t work for us. I think this may be related to it being hard to get anything sensible done in 25 minutes when analysing data or writing a paper. But as mentioned above, I often use something similar when grading papers which works really well.

- Have a “me” day

This is perhaps more for people later in the their careers, but it’s good to have one day a week where you don’t do anything for anyone else, and you don’t go to any meetings. You only do things that will add to your CV. Essentially this means working on papers or grants. Maybe not such a big deal for PhD students, but I can definitely go for weeks without working on any of my research. Another thing to avoid on these days is admin and non-essential emailing.

- Procrastinate effectively

Instead of watching a video of a capybara bathing with ducklings during a break, move on to something that requires zero intellect, but still requires doing for your work, for example reconciling expenses/receipts after a trip, formatting references, playing with figures, searching for new literature etc. Having said that, it’s important to also take proper breaks, and to ensure you see the capybara video.

- More efficient meetings

Another suggestion from @DRobcito was to have 22 minute meetings. We were dubious about this but he claims it works, mostly because you have to cut to the chase immediately. He also suggested scheduling back-to-back meetings to prevent any of them from running over. Again this doesn’t always work and can just lead to all your meetings starting late which may be great for you but is unfairly detrimental to the productivity of the people waiting for you.

- Dealing with emails I

A number of people use the “5 sentence max” email rule to keep emails short and to the point. If an email needs to be longer you should Skype or meet in person. We decided this works sometimes but not others. Many of us like to have details on email rather than talking them through on Skype or in person. Additionally, some of us really hate the trend of really short email replies because it’s hard to gauge tone, and also it seems a bit rude not to address the email to a person. This may be a cultural thing.

- Dealing with emails II

Most of us can’t get much done without internet, so turning off the internet wasn’t an option. But we can all turn off our email notifications on our phones, tablets and computers. This prevents you from dealing with the emails as the come in, but also removes the distraction of the notification itself which can break your concentration. Different people had different strategies for emails. Some do emails in set blocks of time, others do them during breaks. I think in terms of not injuring other people’s productivity it’s probably polite to at least triage your email in the morning and sometime in the afternoon. I also use the rule that if I can respond to the email/do what it asks me to do in less that 5 minutes, I do it then rather than leaving it to fester in my inbox.

- Manage your time, energy and attention.

This article explains this in more detail. Essentially, being productive requires that you have time to work, the energy to work, and the attention to work. Even if you have an hour to work on a paper, you still won’t be productive if you’re too tired to do anything useful or keep getting distracted. All of the above are solutions to one or more of these issues.

Author

Natalie Cooper @nhcooper123

Thanks to @DRobcito, @jonesor and @naubinhorth who helped with suggestions for our discussions.

Photo credit

wikimedia commons