On the 20th and 21st of February we had our annual School of Natural Sciences Postgraduate Symposium. Over the course of two days many of our PhD students presented their work to the School. We also had two interesting plenary talks from Dr Sophie Arnaud-Haond (Ifremer) and Dr Lesley Morrell (University of Hull). Unfortunately our third speaker, Dr Fiona Jordan (University of Bristol) had to cancel due to illness.

For those of you who are interested in exactly what we work on here at EcoEvo@TCD, here are the abstracts from the PhD student presentations. Check out the TCD website for more details!

Aoife Delaney: Eco-hydrology of humid dune slacks*

*Highly commended

Dune slacks are hollows in coastal sand dune systems where the groundwater table is close to the surface. Many dune slacks flood in winter to form temporary ponds which can last from a few weeks to several months. Humid dune slacks are an Annex I habitat (2190) and in accordance with Article 17 of the Habitats Directive they have been mapped and assessed in Ireland on the basis of their vegetation. During monitoring in 2013, Humid dune slacks (2190) were assessed as Unfavourable-Inadequate and topics for further research were identified. The extent and effect of water abstraction and wastewater from recreation facilities has not been firmly established in Ireland, and work relating biological communities to water quality or depth and duration of flooding has focussed almost entirely on vegetation up until now.

This project will assess variation in vegetation, mollusc and water beetle communities present in dune slacks in Donegal, Mayo, Kerry and on the east coast. It will also investigate the effects of land management by comparing biological communities of sites which are under different management regimes such as extensive pasture and golf courses. The hydrological functioning of dune slacks will be related to biological communities they support.

Anne Dubearness: Systematics of the genus Embelia Burm.f. (Primulacae — Myrsinoidae)*

*Highly commended

Primulaceae subfamily Myrsinoideae is a species-rich tropical group containing over 2000 species, with several taxonomically difficult genera with poorly defined limits and many novelties needing description. Within the subfamily, Embelia is a genus of climbing shrubs distributed mostly in South and South-East Asia and tropical Africa. The last monograph of this genus (made by Mez in 1902) recognised 8 subgenera and 92 species, but the total number of species is currently estimated at 140. The systematics of this group needs investigation using a modern phylogenetic approach: indeed, Embelia displays extensive morphological variation (especially regarding the position, shape, size and merosity of the inflorescences) and is only distinguished from other Myrsinoideae by a climbing habit and distichous leaves. This project aims to combine molecular and morphological data in order to investigate the systematic of Embelia at 3 levels: first of all the monophyly of the genus must be tested, then the existing subgenera must be assessed and refined in order to produce a taxonomic framework of the genus, and the final focus will be on the subgenus Euembelia Clarke, which contains more than 65 species and could certainly be split into several sections.

Thomas Guillerme: Combining living and fossil taxa into phylogenies: the missing data issue*

*Highly commended

Living species represent less than 1% of all species that have ever lived. Ignoring fossil taxa may lead to misinterpretation of macroevolutionary patterns and processes such as trends in species richness, biogeographical history or paleoecology. This fact has led to an increasing consensus among scientists that fossil taxa must be included in macroevolutionary studies. One approach, known as the otal evidence method, uses molecular data from living taxa and morphological data from both living and fossil taxa to infer phylogenies. Although this approach seems very promising, it requires a lot of data. In particular it requires morphological data from both living and fossil taxa, both of which are scarce. Therefore, this approach is likely to suffer from having lots of missing data which may affect its ability to infer correct phylogenies. Here we assess the effect of missing data on tree topologies inferred from total evidence supermatrices. Using simulations we investigate three major factors that directly affect the completeness of the morphological part of the supermatrix: (1) the proportion of living taxa with no morphological data, (2) the amount of missing data in the fossil taxa and (3) the overall number of morphological characters for all of the taxa.

Florence Hecq: Effects of scale and landscape structure on pollinator diversity and the provision of pollination services in semi natural grasslands

Over recent decades, humans have been changing the environment more rapidly than in any other period of history. Technological advances and new agricultural policies have led to a simplification of landscape structure resulting in the loss and fragmentation of habitats for flower-visiting insects which play an important ecological role as pollinators. Pollinating insects are very mobile and are influenced by the availability of flowers and nest sites over a scale of several kilometres.

In this study, we investigated the effects of the complexity of landscape structure on the diversity of four pollinating taxa and on the provision of pollination services to four plant species. Pollination data were collected in 19 semi-natural grassland sites in north midlands region of Ireland and related to the composition and configuration of surrounding landscape at two spatial scales (500m and 1km radius around sampling sites). Landscape structure was characterised by digitising each landscape feature with aerial photographs and GIS, and then ground-truthed using field-based surveys. Knowledge of these pollination/landscape scale relationships is crucial for a better understanding of pollinator diversity patterns and should be helpful for future conservation management decisions; ensuring essential levels of pollination services to wild plants are maintained.

Lindsay Hislop: Does nutrient enrichment moderate the effect of water level fluctuations on littoral communities?

Freshwater abstraction from lakes in order to support a growing human population is rapidly becoming a major global stress on lacustrine ecosystems. The consequent amplification of water level fluctuations disproportionately impact lake littoral zones, which contain the majority of their biological diversity. However, remarkably little is known about the impacts of amplified water level fluctuations on littoral assemblages and less still is known about how they interact with nutrient enrichment, one of the most pervasive and important of human disturbances on the biosphere. To address this, we established an experiment in large outdoor pond mesocosms where we quantified the effects of water level fluctuations and nutrient enrichment, both separately and together. We found that the impacts of water level fluctuations on both primary producers and benthic consumers varied significantly along the depth gradient. However, we found no interactions between nutrient enrichment and water level fluctuations. Given that the problem of amplified water level fluctuations is likely to be exacerbated considerably by predicted increases in climatic variability and enhanced water demand, our findings have profound implications for the conservation and management of global aquatic biodiversity.

Nuria Valbuena Parralejo: The impact of artificial sub-surface drainage on greenhouse gas emissions, change in soil carbon storage and nutrient losses in a grazing cattle production system in Ireland

In Ireland, over the 33% of milk is produced on a Heavy Soils farms. Heavy Soils are characterised by low permeability and often form in high rainfall areas. The combination of both can lead to waterlogging, promoting soil compaction which significantly affects the grass production. Drainage has been shown as an effective tool for improving the soil permeability. Little data is available to assess the effect of the artificial subsurface drainage of a grassland production system, on greenhouse gas emissions, change in soil carbon storage and nutrient losses. This experiment will be carried out in Teagasc Solohead Research Dairy Farm (latitude 52° 51’ N, 08° 21’ W; altitude 95 m a.s.l.). Different treatments (i) mole drain winter, (ii) mole drain summer, (iii) gravel mole and (iv) control were imposed in one site of the farm in 2011. A new experiment will be set up at a different site on the farm in summer 2014 with (i) control and (ii) gravel mole into collectors. Nitrous oxide (N2O) flux measurements, soil respiration measurements, soil total carbon and total nitrogen analysis, soil nitrogen mineralisation and net nitrification, water analysis, water table measurements and herbage production will all be perform in both sites over two years.

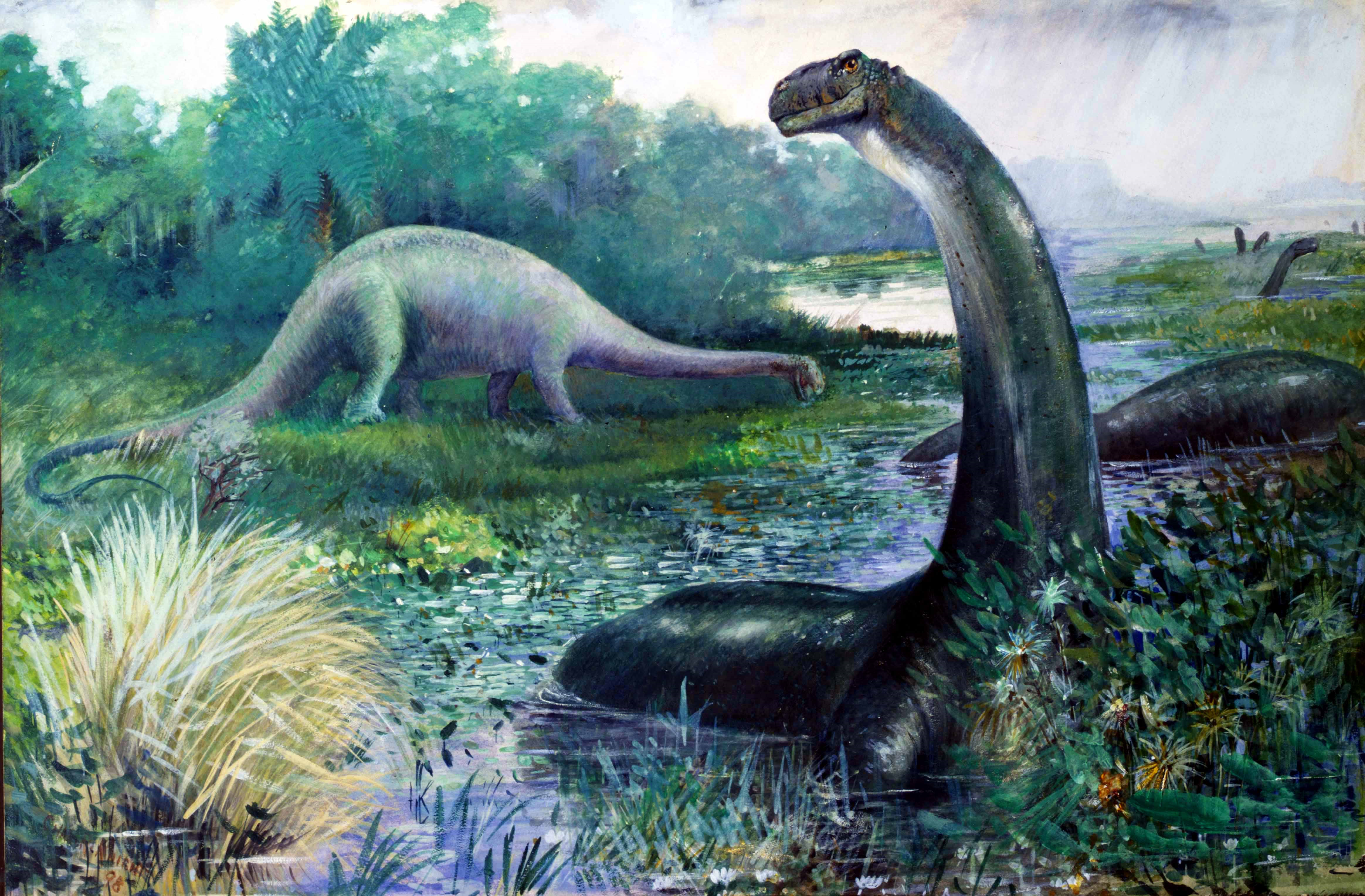

Adam Kane: Ontogenetic dietary partitioning in Tyrannosaurus rex*

*Highly commended

Obligate scavenging in vertebrates is a rare mode of life, one which requires very specialized morphologies and behaviours to allow the scavenger to cover enough area to find sufficient carrion. Yet, a number of studies have suggested that Tyrannosaurus rex occupied this niche with others arguing for its role as an apex predator. In this study we move away from the polarised predator-scavenger debate and argue that T. rex underwent an ontogenetic dietary shift, increasing the proportion of carrion in its diet as it aged due to both the increased availability of carrion through direct intraspecific and interspecific competition and also by exploiting resources unavailable to its smaller competitors, namely bone. We follow an energetics approach in our study to explore the effect of this previously unrealised resource on the ecology of T.rex and look at the impact of the proposed ontogenetic dietary shift.

Image Source: Wikicommons