I’m going to Madagascar tomorrow.

I have all the essentials; insect repellent, tent, flat pack wooden box, bat detector, three metres of blackout curtain material… Not the most usual of packing lists admittedly but all necessary items for the trip ahead.

I’m going to study tenrecs; cute mammals which are the subject of my PhD. I’m interested in convergent evolution between tenrecs and other small mammals. So far I’ve been focusing on morphological convergence – work which has involved trips to beautiful museums and taming the dark arts of morphometrics. The primary aim of my research is to assess the evidence for morphological and ecological convergences among tenrecs and the mammals they resemble. Technically I could complete these aspects of the project without ever seeing or dealing with the live animals. But where’s the fun in that?! I’m also interested in behavioural convergences among tenrecs and other mammals, particularly reports of the abilities of some tenrecs to echolocate.

Some shrews produce echolocation calls by clicking their tongues. More recent work indicates that shrews seem to use these clicking calls primarily for navigation within their habitat rather than communication. Intriguingly, there is evidence that at least three species of tenrec; the lesser hedgehog tenrec, lowland streaked tenrec and Dobson’s shrew tenrec, can also echolocate. The animals seem to use their tongue clicks for navigation. The stridulation sounds produced by specialised spines in lowland streaked tenrecs and juvenile tail-less tenrecs have also been linked to having an echolocatory function but immobilising the spines doesn’t seem to affect the animals’ abilities to navigate by sound.

These early experiments are tantalising evidence of intriguing behavioural convergences among shrews and tenrecs. However, limitations of 1960’s acoustic technology and the ever so slight changes in standards of experimental practice (blinding animals with cement doesn’t go down so well with modern ethics boards!) mean that the study of echolocation in tenrecs is ripe for further exploration.

Hence my unusual packing list. My plan is to place wild-caught tenrecs within a box that can be converted into a maze of various layout and complexity (I’m extremely grateful to our super technician, Peter Stafford for making an adjustable maze which can be flat-packed for travel to Madagascar!).

Using a bat detector, I’m going to record the sounds produced by the animals both when they’re “at rest” just in the empty box and when faced with the task of moving through the maze to reach food at the other end. I’m going to observe and film the animals moving through the maze, both in daylight and under red-light conditions in darkness (hence the blackout curtains) and record the sounds they produce as they move. The idea is to test whether the animals’ call patterns (structure/frequency of calls) changes as they navigate their way past an obstacle in the maze. Bats are known to modulate their call frequencies when they hone in on their prey or to navigate their way past obstacles. I want to test whether there’s similar call modification in tenrecs which would provide evidence that the animals are actually using their echolocation sounds for navigation. It would be fascinating to understand more of how tenrecs use echolocation and to test whether other tenrec species can also echolocate.

It all sounds quite straightforward but I’ve experienced some of the vagaries of fieldwork in the past and I’m anticipating many more problems to come. I’ve received advice and war tales from researchers who have tried to study echolocation in shrews only to be thwarted by problems of distinguishing the animals’ calls from background sounds or the noise of the animal’s claws on a wooden base. Similarly, the tenrecs may not want to cooperate with my idea of moving from one end of the maze to another. I’m hoping that a nice juicy earthworm at the other end will act as the metaphorical carrot but there’s no way to know until we actually try it out. Furthermore, it might be difficult to distinguish sounds that say “I’m scared of being in this box” from sounds that the animals are using for navigation. Similarly, since we have neither the option nor inclination to experimentally blind or deafen the animals we won’t be able to completely exclude the possibility that the animals are using other sensory cues aside from acoustic navigation.

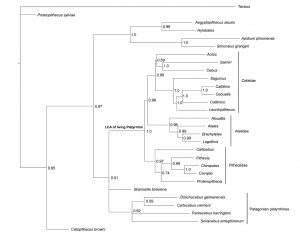

Even still, I’m hoping to get results which demonstrate the range of calls produced by tenrecs and which provide clues into how the animals use their acoustic behaviour to their advantage. Echolocation has involved independently in different animal lineages. Most interestingly, there is even clear evidence for convergence at the level of genetic sequences. Hopefully the data I gather over the next few weeks will add to our understanding of this fascinating story of convergence among tenrecs and other mammals.

And maybe we’ll spot a few lemurs on the way…

Author: Sive Finlay, sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay

Image Source: S. Finlay