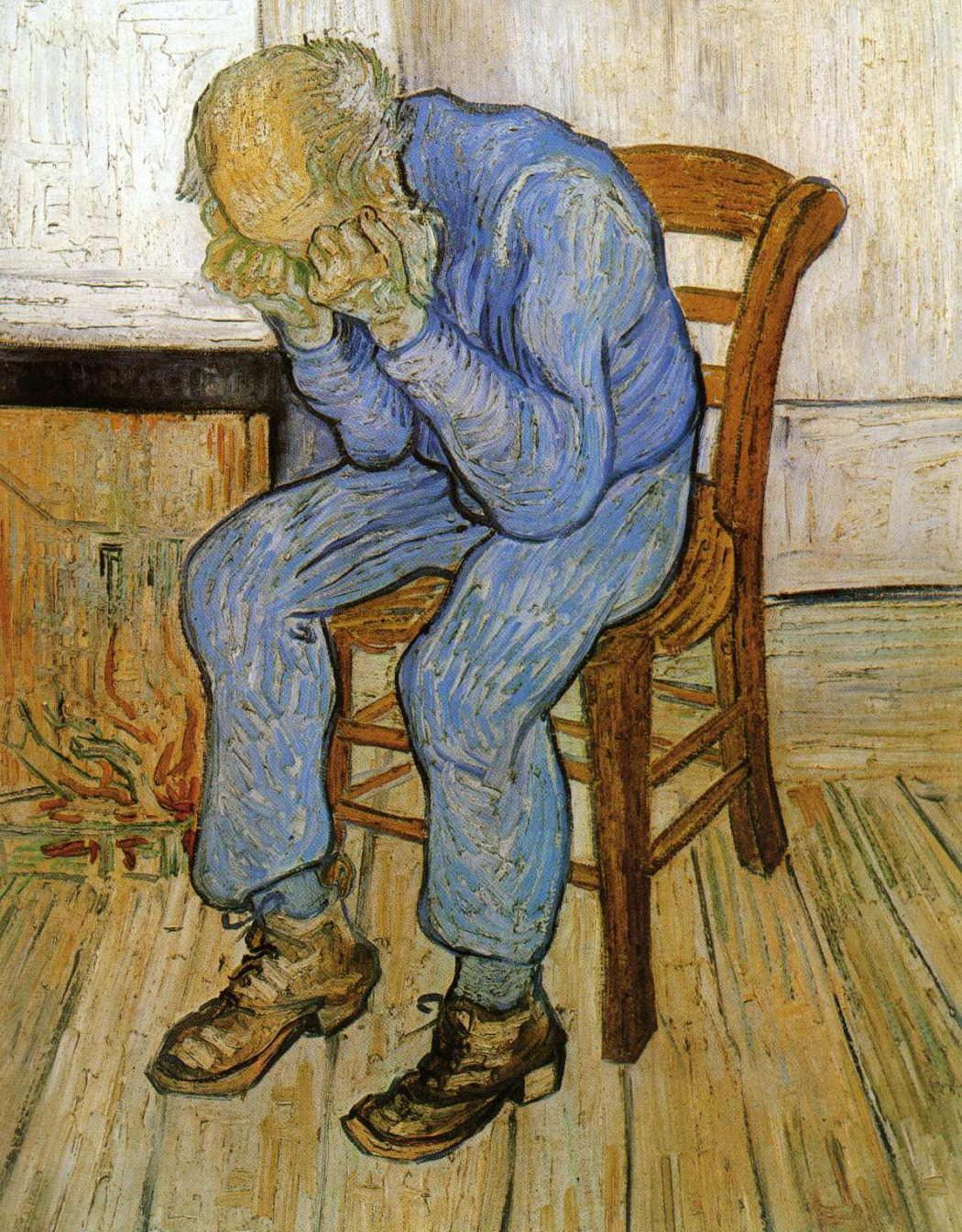

Inspired by recent reports of rising mental health problems in academia plus an acute increase in stress around the department this summer when many PhD students were writing up, we decided to run a “Dealing with stress” seminar at NERD club (ironically this session was canceled previously due to the PIs being “too stressed” to run it!). It turned out to be a really positive experience, and I’d definitely run something similar again. Here is what we found out!

What is stress and why is it bad?

Stress is an “adverse reaction to excessive pressure”. Short term stress responses can actually be beneficial, either for escaping angry bears or finding that last bit of energy needed to finish a manuscript, thesis or endless admin task. However, longterm chronic stress is really bad for you. Symptoms include headaches, nausea, digestive problems, ulcers, lowered immune responses, changes in appetite, altered sleep patterns, mood swings, lowered self esteem, negative thinking and more. All of these can trigger chronic mental health issues like depression and anxiety.

What causes stress?

Causes of stress are really varied; what stresses one person out has no effect on someone else. Some articles put causes of workplace stress into six categories: (1) too many demands; (2) too little control; (3) poor relationships with coworkers/superiors; (4) too much change; (5) too little support and (6) lack of clarity about your role. Unfortunately, as one PI pointed out, these six things define academic jobs!

We started our stress seminar by independently writing down everything that made us stressed/worried on Post-It notes and then placing these into a bin at the centre of the room (this was for convenience but I guess you could say we were symbolically throwing our troubles away…). We then shared these with the group. Unsurprisingly we’re stressed about similar things. I expect you’ll recognise some of the following:

Lack of structure/direction, pressure to come up with new ideas, balancing fun stuff with work stuff, the two body problem, struggling students, R, GIS, statistics, field work, risk assessments, paywalls, graphs, “the literature”, bad paper reviews/rejections, losing data due to a bug, forgetting deadlines, worry about not finishing PhD on time, feeling out of control, lack of public understanding of science, admin, pressure to produce outputs more regardless of quality, letting people down in and out of work, dealing with conflict/difficult meetings, saying yes too much, grant writing/rejections, public speaking, and, my personal favourite, how much coffee is too much???

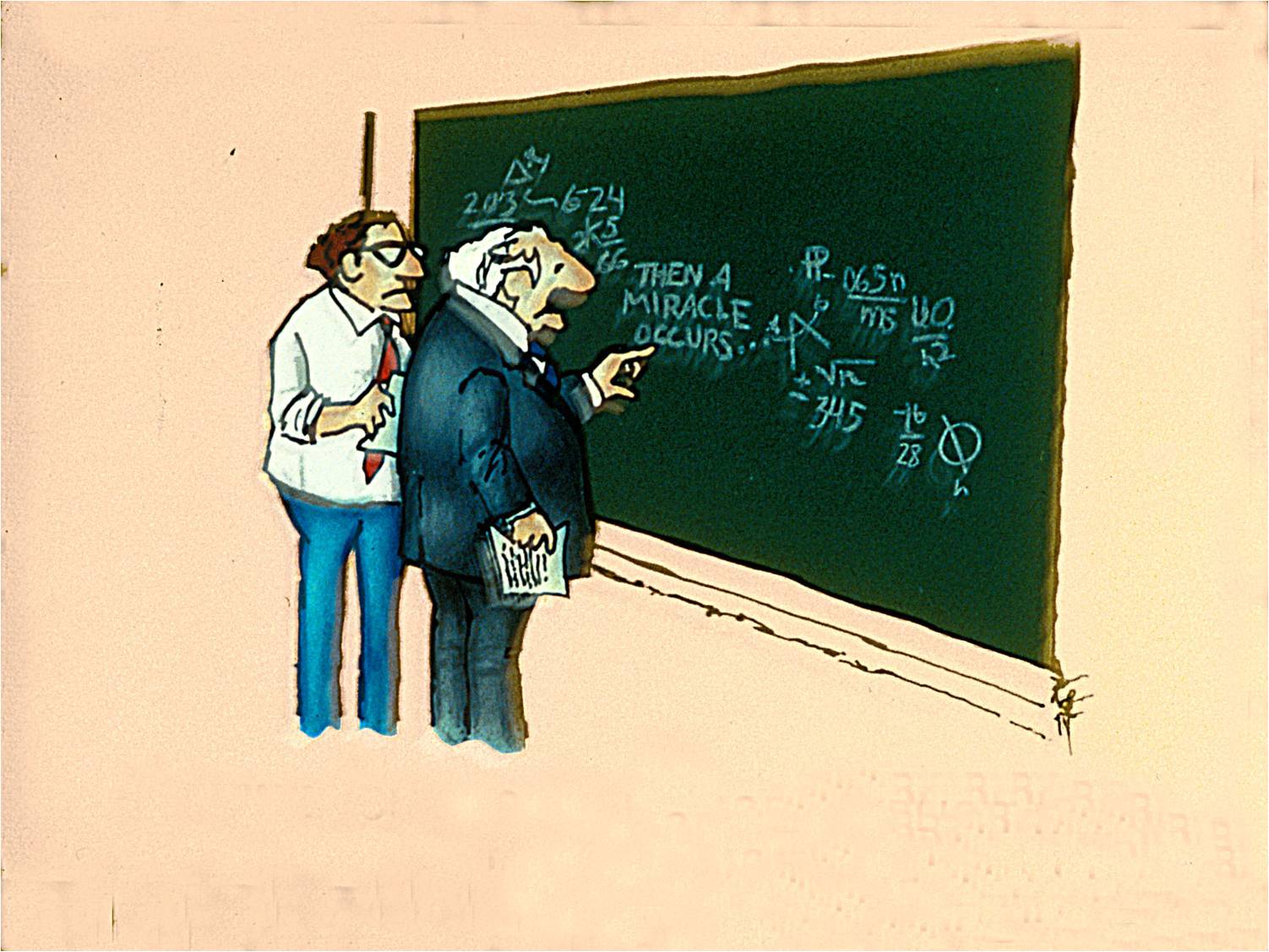

We also had several things that everyone was stressed about. These were deadlines (aka having too much too much to do and too little time to do it), career uncertainty (sadly not something we can solve), and a lot of worries that fall under the category of impostor syndrome. The latter included worries about finding errors in data/analyses after submitting/publishing papers, worries about saying stupid things in front of people, feelings of inadequacy in relation to others and to your own potential, fear of failure etc. Generally the terror of being “found out” for being too stupid to do research. I think most of us found it quite reassuring to share these fears, including the PIs!

How can we reduce stress?

There are lots of suggestions online for reducing stress (including dowsing your house for geopathic stress – hmmm yeah…), here are just a few we discussed:

1) Talk about it.

Talk with family, friends, workmates or anyone really. If you’re having problems at work it’s a good idea to talk to your supervisor or line manager, or another staff member if your supervisor is the problem! Many of us also flagged how useful it is to speak to a professional counselor when problems get too big for you to handle alone (most universities offer free services to staff and students). An important point was that you shouldn’t be embarrassed – everyone feels stressed sometimes and it is not a sign of weakness.

2) Look after yourself.

Get plenty of sleep and exercise, don’t drink too much caffeine or alcohol, and try to eat a well-balanced diet (apparently chicken dippers are fine because BBQ sauce counts as a vegetable).

3) Learn to notice when you’re stressed and do something about it. If you don’t realise you’re stressed it’s hard to solve the problem, so learn the warning signs and symptoms and act accordingly when you notice them. It may help to keep a stress diary to work out what triggers your stress, and then avoid those situations and/or people!

4) Increase your productivity.

Many of the issues of having too much to do, or worrying about deadlines, can be helped by increasing your productivity and/or improving your time management skills. Check out the tips here for some ideas. The most important point here was to “work less but achieve more” rather than working ridiculous hours. Which brings us to idea 5…

5) Lower the bar!

If you come into work and have big plans for the week but don’t achieve them (for whatever reason), you tend to feel crap. Instead, set a lower bar. In fact, set a *really* low bar that you can hardly fail to meet. Even though you know your bar was low, you’ll still feel better having finished something! To help with this, try breaking tasks into smaller, more manageable chunks. For example, aim to finish the introduction of a paper rather than the whole paper. Oddly enough I finish things more quickly this way than if I work my ass off trying to achieve my grandiose aims!

6) Have a Plan B.

Although we can’t fix the problems with the academic career pyramid scheme, we did come up with some suggestions to reduce stress about it. Most of the PIs revealed that they had a Plan B (and Plan C) for if academia hadn’t worked out for them. This made them feel less panicked when approaching the end of contracts. Additionally, we decided we would look at our CVs and extract skills that would be useful in non-academic professions. PhDs train you for all kinds of jobs even if we don’t talk about them much. Knowing there are other options out there will hopefully reduce stress.

7) Dealing with impostor syndrome.

We spent a long time discussing this, and no-one really had a solution. Unlike many of the other problems which have external causes, this is an internal perception problem that is hard to fix. Instead focus should be on recognising it and dealing with it rather than eliminating it. Even the Chair of our department feels this way sometimes! Talking to other people should help (especially people you look up to), also trying not to compare yourself to others and realising that everyone has very different skills. A student with a lot of fieldwork shouldn’t expect to produce as many papers as a student working on an existing dataset for example. This is really hard in academia because there will *always* be someone out there who is better than you at something. But my favourite piece of advice on this is that people who never suffer from impostor syndrome are probably faking it, or gigantic assholes.

Hope some of this is helpful! Now go and lead less stressed lives!

Author

Natalie Cooper, ncooper[at]tcd.ie, @nhcooper123

Photo credit

wikimedia commons