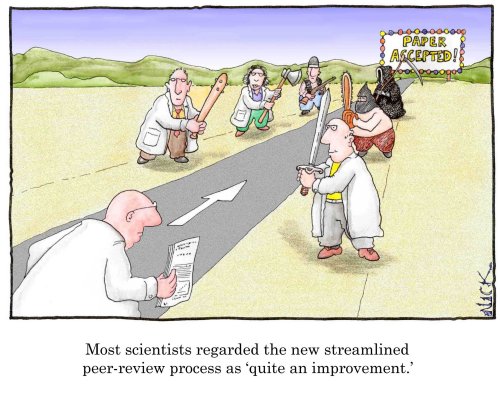

Every now and then you stumble on a paper that changes everything for you. Typically something of a personal zeitgeist moment, it opens your eyes to a whole new world of potential and can spin your own research out in new directions, or encourage a complete re-orientation of your goals. In this new series, we are going to profile some of our favourite papers and maybe share the inspiration a little wider.

I don’t get out from behind my computer much, but when I do, my favourite engagement with real animals is to watch swirling flocks of starlings or trails of ants in search of food.

During my PhD I was working on the evolution of behaviours in social groups when I stumbled on a paper as I was searching through my supervisor Prof Graeme Ruxton’s publications. This was one of the first collective behaviour papers I read, and it was a huge eye-opener for me, pandering to both my love of biology and computers. Collective memory and spatial sorting in animal groups by Couzin, Krause, James & Ruxton brought home for the link between individual behaviour, self organisiation, emergent behaviour, complex biological pattern formation and how evolution could exploit this system and shortcut adaptive strategies without the need for invoking complex cognitive processes.

The concept itself wasn’t new: Craig Reynolds in 1986 demonstrated that interacting individual computer animals, which he termed boids, following three basic rules of separation, alignment and cohesion could generate a variety of complex group level patterns akin to biological swarming, shoaling and flocking. This simple computer simulation showed how the interactions themselves could create coordinated group-level behaviour without a need for centralized control, or for agents to possess any knowledge of their surroundings beyond their nearest neighbours. Instead, the patterns are an emergent property of the system of interacting agents that arise through a process of self-organisation. Craig Reynolds went further, and showed that information could be transmitted through the group so that obstacles (or predators) could be avoided by individuals responding to their neigbours avoidance, without having to actual see the obstacle or threat for themselves. Such characteristics have clear selection benefits in an evolutionary sense whereby there are cheap, effective ways to gain benefits of living in large collective groups.

What Couzin et al did was to show in even more detail the ecological and evolutionary relevance of these systems. They described in detail how subtle changes to individuals’ behaviours, manifested in adjustments to the radii that define whether they avoid, align or cohere with their neighbours, could arise in abrupt changes to the group-level pattern. A system dominated by attraction and avoidance tends to produce swarming behaviour around a relatively stationary point whereas one dominated by alignment produces shoals that move in a rather rigid, elongated diamond-like formation. In between there exists an intermediate state in which the group spontaneously starts to rotate in a torus (ring-doughnut) structure. The key point here is that no-one in these groups knows what a torus is, never mind how to achieve it, and nor is there a leader telling them to swim in a circle – rather, it is an inevitable consequence of the aggregation of the interactions between individuals with a mid-range tendency for alignment. An extra quirk to the system is that though the individuals are completely bereft of any brain or memory, the system shows evidence of memory – or hysteresis as physicists would refer to it. Individuals starting in a swarming pattern and increasing alignment will move through the rotating torus and on to the rigid diamond-like structure with individuals locked into a particular place in the group. However, if you start with the rigid structure, and reduce individuals’ tendency for alignment, they skip the torus structure and revert straight to swarming. In this manner, the group has memory of what it was doing in previous states, even though the individuals have no such memory. This is surely a rather cheap way for interacting ants, fish, birds, or maybe even the neurons of our brain to encode a sense of memory or history without having to explicitly encode and record the details of past states.

Perhaps most relevant from a behavioural ecology perspective, Couzin et al went further and explored how changes to an individuals behaviour relative to the group could alter its location. Increasing speed, decreasing turning rate or increasing one’s tendency for alignment would see an individual end up towards the front of the group. Reducing ones tendency for avoidance would see an individual move to the centre of the group. This is beautifully simple. Without any knowledge of the group structure, or where one is in the group, simple behavioural rules linked to internal state can now allow an individual to navigate the group. For example, if hungry, simply speed up and you will be at the front with first access to food. Once sated, you can seek out the relative safety of the middle by reducing your how much ‘personal space’ you require.

Prof Iain Couzin has gone on to show myriad intricacies of collective groups in terms of how they can make decisions as a group, and how locust swarms are driven by similar properties. During my PhD I had the pleasure to meet with Iain Couzin, study under the tutelage of Graeme Ruxton, share code with Richard James, and collaborate with Jens Krause (I didn’t get to meet the last author Nigel Franks, but now that I’m back on the conference tour there is still hope!)

Author

Andrew Jackson

Photo credit

wikimedia commons