![image[3]](http://www.ecoevoblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/image3-300x300.jpg)

Aoibheann Gaughran (@Aoibh_G)

Supervisor: Nicola Marples

Title: How population density influences social mammal ecology: A case study of the European badger.

The local density of a population of social mammals can affect many aspects of its ecology including social structure, mating systems, dispersal behavior, territorial behavior and the dynamics of disease. Scientists and policy-makers need a comprehensive understanding of the local population density as this may dictate the most effective management strategy. The European badger provides a particularly good species to investigate the effects of population density on other density parameters because its density varies by orders of magnitude across its wide geographic range. Further, it acts as a wildlife reservoir for bovine tuberculosis in the UK and Ireland, where it is subject to control operations. Currently, a haphazard classification of local population densities hampers a clear understanding of the badger’s ecology, leading to inappropriate management systems. We have conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the relationships between social group size, territory size, and group density and population density in badgers. We demonstrate that population density fundamentally alters badger ecology, affecting the interactions both within and between social groups. We also propose a classification system for densities of the European badger which highlight important ecological differences between populations across the density spectrum. Our findings provide a more cohesive picture of the species’ ecology across its range, facilitating appropriate targeting of disease management and conservation regimes.

Michelle McKeon-Bennett

Supervisor:Trevor Hodkinson

Title: Characterisation of endophytic microbes within Sphagnum magellanicum from Clara Bog, County Offaly, Ireland: Implications for enclosed environment hydroponic systems in Space.

This work investigates potential mutualistic relationships between endophytic microbes and species of native Sphagnum moss sampled from Clara Bog, County Offaly, Ireland. The application of the ion-exchange ability of Sphagnum moss to water remediation and recourse recovery within an enclosed hydroponic system has been investigated by the author at NASAs Space Life Science Laboratory, Kennedy Space Centre, Florida. While this research indicated that Sphagnum could be utilized in this manner, it resulted in yet more questions, specifically in relation to microbial interactions and growth mechanisms within the Sphagna:plant test bed.

It is postulated that endophytic microbes growing mutualistically within S. magellanicum may be responsible for (a) anti-algae and anti-microbe effects within the hydroponic system and (b) increased nutraceutical content within the associated salad crop. Microbial DNA isolated from 100ug samples of S. magellanicum, was extracted and used to identify microbial endophytes using standard barcoding primers. Genetic fingerprinting is being utilised to type the endophytes. Isolation and culturing protocols from Sphagnum plants have been developed and applied for the characterisation of microbial species during hydroponic systems using S. magellanicum as a growth medium. Further investigation of mutualism between identified endophytes and a cultivar of Lactuca sativa known as ‘Lollo Rosso’ is ongoing.

Alex O’Cinneide

Supervisor: Anna Davies & Martin Sokol

Title: The effectiveness of renewable energy policies in encouraging renewable energy generation.

Over the last twenty years the EU and its individual countries have been engaged in implementing policies to increase the use of renewable energy (RE) as a generation source. Motivations for this support of RE generation include, but are not limited to, concerns over climate change and pollution, national security risks associated with fossil fuels, and a wish to increase the competitive position of RE in markets which have been traditionally dominated by carbon based power. The issue of climate change and renewable power’s role in addressing this complex challenge has, in particular, been brought into sharper focus following agreement on emissions pledges from all the EU countries, and a new target of keeping global warming below 1.5C in December 2015 in Paris at COP 21; targets which will require a material response by policy makers throughout the EU. An understanding of what policies have been most effective in increasing RE is therefore critically important in designing new schemes, a comprehensive analysis of which has not been completed to date. I am therefore conducting a comparative analysis of the effectiveness of RE policies in encouraging RE generation (solar and wind, which given their advantages in cost and deployment have been the dominate focus of policy) across the EU from 1995 to 2015, with a primary focus on four countries of contrasting contexts, Ireland, UK, Italy and Portugal. While several studies have attempted to determine the effectiveness of various policies in various countries, these have been limited in scope and have not attempted to account for the variety of policy design features or individual country, market and key actor characteristics that influence policy strength. Adopting an energy transitions theoretical framework, this research would constitute the first study undertaken to determine how policy has effected the growth of renewables across Europe.

Anne Dubéarnès

Supervisor: John Parnell & Trevor Hodkinson

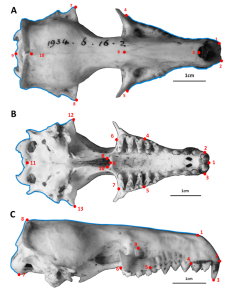

Title: Systematics of the genus Embelia Burm.f. (Primulaceae – Myrsinoideae)

Within the Primulaceae family, the Myrsinoideae form a highly variable tropical group, ranging from climbers and shrubs to trees, and characterised by the presence of dark dots on the leaves and fruits. This subfamily contains over 1300 species, divided into approximately 40 genera. Many of these genera are in need of taxonomic revision, as their limits are poorly defined and sometimes rely on ambiguous characters. Among these genera is Embelia, a genus of climbing shrubs distributed mostly in South and South-East Asia, tropical Africa and Madagascar. Embelia displays extensive morphological variation – especially regarding the position, shape, size and merosity of the inflorescences and flowers. It is distinguished from other Myrsinoideae only by the climbing habit, and the relationship with morphologically similar genera has not been critically evaluated yet. The last monograph of Embelia by Mez (1902), recognised eight subgenera and 92 species, but the total number of species is currently estimated at 150-200, and the subgenera used by Mez must be assessed and refined. My project aims to combine morphological and molecular data in order to test the monophyly of Embelia and to provide a taxonomic framework of the subgenera.

Eoin Mac Réamoinn

Supervisor:Cliona O’Farrelly & Paula Murphy

Title: Toll-Like Receptor Gene Expression During Early Murine Embryonic Development.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are renowned for their fundamental roles in immunological surveillance and response initiation. While TLR proteins in invertebrate species, such as Drosophila, carry out functions in the immune system and in “building” the body plan in the embryo, such non-immune functions have not been thoroughly investigated in mammals. Although TLR genes have duplicated independently in these lineages, and may therefore have diverged in aspects of their functionality, limited studies have recently reported the expression of TLRs in the developing mammalian embryo (Kaul et al., 2012). We report a systematic study of Tlr gene expression in early to mid-gestational murine embryos using whole-mount RNA in situ hybridization and 3D imaging (using Optical Project Tomography), the combination of which has allowed us to record the precise tissues and stages at which these genes become expressed. We have found that the expression of these receptors is particularly enriched within the central nervous system with many Tlrs displaying complementary expression patterns in developing neural tissues, as is the case with Tlrs -1, -5, -6, and -7 in the neural tube at embryonic day 10.5. These findings are in line with experimental data showing that Tlrs -2, -3, and -4 can influence neural progenitor cell proliferation and self-renewal (as reviewed in Barak et al., 2014). In addition to the expression data we have generated, whole-transciptome data is being mined to build a comprehensive picture of Tlr activity during embryogenesis and will aid in the building of specific hypotheses for functional testing.