Are you a hard or soft scientist?

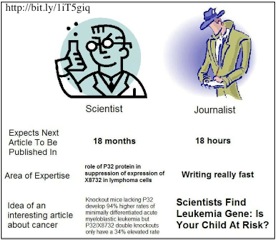

According to one 19th century science philosopher, the hierarchy of scientific disciplines is strictly segregated with physics and chemistry at the top, biology somewhere in the middle and social science towards the bottom (while astrology and homeopathy must occupy some nether-regions in the bowels of patently unscientific pursuit). The stereotypical view of hard scientists; scrawled equations, incomprehensibly complicated diagrams and lab coats which have definitely seen better days is in stark contrast to their soft scientist cousins; glorified stamp collectors who get into a tizzy over the finer details of the classification of the lesser-spotted something or other. There’s even a hard/soft distinction within biology; surely playing with genes, molecules and machines that go “ping” must be far more scientifically rigorous than conducting habitat surveys or behavioural experiments? I’m not suggesting that societal perception of scientific research is always so limited but the underlying biases, however subconscious, do remain.

The perceived differences between hard and soft seem to stem largely from the degree of mathematical theory underpinning your research. Physics involves maths; maths is hard therefore physics is a hard science. In contrast, traditional biology is merely comprised of learning the parts of the body and possibly frolicking in a few fields. There’s little or no maths involved so biology must be soft. Gross simplifications they may be but I think these views echo the underlying biases of many people, scientists included. They are, needless to say, rubbish.

For a start, maths is inescapable in all sciences. Elaborate equations filled with strange symbols are alive and well in all aspects of biology and social sciences. Ecologists are no more immune from the necessity of mastering mathematical concepts and techniques than their physicist brethren. Admittedly, the prominence of maths does vary according to research discipline; theoreticians are far more likely to be concerned with the finer details of some statistical method than the field biologist applying that method to study changes in squirrel populations. However, to claim that modern research in traditionally softer sciences is any less maths-reliant than the hard sciences is clearly misguided.

So if maths is inescapable does that mean that all science is hard? Well yes. To the extent that all, true science (i.e. hypothesis-driven, testable predictions with proper application of the scientific method) involves maths then yes all science is “hard”. But the application of mathematical techniques doesn’t necessarily deserve the exalted position it receives. Quantitative tests and mathematical models are all well and good but they’re virtually meaningless without real-world observations and predictions as their basis. Maths must be informed by the “softer” side of qualitative scientific observations.

Similarly, maths can be difficult, sometimes even impenetrable when it reaches the upper echelons of some complicated proof for a theory which you don’t understand in the first place. But I don’t think that maths deserves to be seen as any harder than other subjects. Leaving Cert students are now awarded bonus points for passing higher level maths. While the scheme has encouraged more students to stick with higher rather than ordinary level maths it also has the unfortunate effect of perpetuating the view that maths is harder than any other subject. Hopefully the new Project Maths syllabus will help to knock maths off its rarefied pedestal and make it more accessible to students (although the desired effect does not seem to have kicked in yet).

So break down the scientific class structure and don’t be intimidated by the special scientists with machines that go ping. Rather than nonsensical notions of hard vs. soft or hierarchies based on who uses the most complicated maths, it would be far more productive to concern ourselves with the distinction between good vs. bad science. The differences can sometimes be hard to spot but critical understanding of which scientific findings to trust is far more important than any outdated rivalries between the frizzy-haired physicists and glorified beetle collectors of bygone eras.

Author: Sive Finlay, sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons