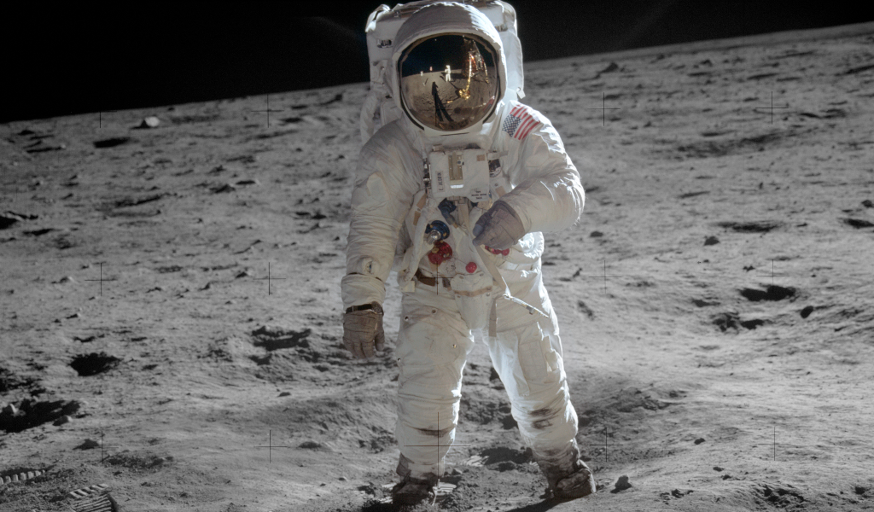

Space: the final frontier. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing mission; the first time we had ever stepped foot on the moon. As Neil Armstrong boldly declared “that’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”, we perhaps reached a new peak of human achievement. A peak that continues to climb upwards, itself shooting for the moon.

I’ve grown up with franchises like Star Wars and Star Trek. Where somehow there’s always a white (human) man getting into trouble with aliens and flying space ships. One thing that’s common in much science fiction is the idea that we can colonise new worlds, terraforming their surfaces to sustain life (as we know it). This idea is pervasive in the years since the moon landing, and continues to be drawn upon even in recent films claimed to be scientifically sound (e.g. Interstellar and The Martian). Whilst this is a romantic idea—of humans gallivanting across the galaxy (hitchhiking even)—I sometimes worry about the price of this dream. Of course, I’m sure the notion has inspired many great minds the world over to learn about space, and perhaps to successfully take us all there one day. But does this idealism come with a cost?

Continue reading “Moon Landing Anniversary – Don’t look to the stars when the ground is burning”