Before I moved to New Zealand birds were, well, birds. They were nice to see but I didn’t pay them much attention. But New Zealand is a bird paradise and as a biology student (I studied for my undergraduate degree at the University of Auckland) birds were the go-to exemplar of many biological concepts. With understanding often comes interest and I found myself increasingly interested in our avian friends, an interest which has stayed with me to this day.

New Zealand is a unique landmass. It comprises two main islands (imaginatively named the North and South Islands) and a number of smaller islands, stretching from the Kermadec Islands in the subtropics to the Campbell Islands in the subantarctic. It separated from Gondwana around 65 mya, just at the time that the first mammals were evolving. This separation prevented any land mammals from reaching the islands which had far-reaching impacts on the evolution of the remaining fauna and flora.

In the rest of the world mammals have evolved to fill almost every niche. In New Zealand their absence has allowed other fauna to evolve to fill those niches, providing an interesting natural ‘what-if’ experiment. For example, in the place of the mouse New Zealand has the weta, a large insect (that also gave its name to Peter Jackson’s special effects company). A fun way to spend an afternoon is looking at different New Zealand animals and trying to work out their mammalian counterpart.

While there are many interesting animals in New Zealand (I must remember to write about the tuatara some time) the stars of the show are definitely the birds. Some are quite famous. The kakapo gained global fame following Douglas Adam’s book “Last Chance to See”, written in 1989 with Mark Carwardine. At the time of writing the outlook for the kakapo looked bleak but a follow-up programme in 2009 with Stephen Fry replacing the late Douglas Adams found a far rosier picture thanks to the Kakapo Recovery Programme, which only recently celebrated the birth of yet another chick. Others, such as the kereru, are barely known outside New Zealand and not particularly revered within. A shame, I think, as they are beautiful birds and worthy of recognition.

If you had to name one feature of New Zealand avifauna it would probably be the preponderance of flightlessness. In the absence of mammals, flight became a burden rather than a blessing. Flight is, after all, much more energetically costly than walking. There used to be far more species of flightless birds but the arrival of the Maori, around 1250 – 1300CE (a mere 750 years ago!), led to the extinction of many through hunting, habitat loss and the introduction of the Polynesian rat or kiore (Rattus exulans), the Moa being only the most famous.That’s not to say that there weren’t predators, there were. It’s just that flight wasn’t the ultimate escape plan it used to be and evolutionary pressures were lower due to the lack of any Johnny-come-latelies that the rest of the planet were experiencing in the form of mammals. So New Zealand became a bit of a back-water, an evolutionary side street where the hustle and bustle of the modern mammal-dominated world was a distant and untroubling thought.

Over the course of the 65 my until man arrived on New Zealand’s shores, many bird species arose. The kakapo, kea and kaka, arguably three of the most well-known birds outside the eponymous kiwi, are all thought to have the same common ancestor. They are all members of the Strigopidae, a family endemic to New Zealand, having evolved around the time of the separation from Gondwana. The kakapo evolved first, around 60-80mya, then the kea and kaka evolved during a period of orogeny (mountain building) and sea-level change between 1 and 4 mya through ecological divergence. The kea is the world’s only alpine parrot and is thought to have evolved during periods of glaciation, diverging from the proto-kaka. Subsequent glacial-interglacial periods led to the evolution of the various sub-species of kaka found in the North and South islands as well as some of the other offshore islands. It is a forest parrot and feeds on a range of invertebrates and plant parts. At certain times of the year nectar produced by scale insects is a major component of their diet, and competition with introduced wasps has had major impacts on breeding success and survival.

The kereru, the final species I want to discuss today, is probably my favourite of the bunch. They are much more common than the others, though that’s not to say they aren’t experiencing problems, and there was many a day when my walk to the bus was brightened by seeing one of these beautiful and surprisingly large birds. They are incredibly noisy fliers. When they take off they make a ‘wing-clap’ and in flight they make a whooshing sound so you always know if they are around. They are quite bold and when feeding on the ground you can get surprisingly close.

Kereru nest in trees. This was a ridiculously safe place to nest (though their nests aren’t the most solid of constructions) until the brush-tailed possum was introduced for the fur trade. Possums (and other introduced mammals such as stoats and rats) predate on eggs and chicks. Given that kereru have a naturally low reproductive rate (in common with many New Zealand species) this predation has had severe impacts on the population stability.

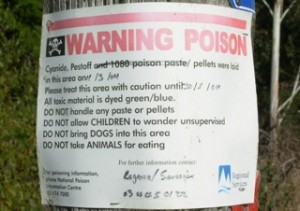

Introduced pests are the main threat to New Zealand’s avifauna. Luckily the country’s government and conservation groups have taken a pro-active role in reducing this threat. One of the benefits to being a naturally mammal-free nation is that solutions unfeasible elsewhere can be used. The most well-known of these is the use of the poison 1080. Lethal to mammals in low doses, but only toxic to birds at high doses, it is used across New Zealand to kill possums and other pests. Its use is not without controversy as it sometimes attracts pets such as dogs and cats, but it has been highly effective, particularly when used with other methods such as trapping and fencing areas.

The avifauna of New Zealand is unique. Many species are long-lived (kakapo are thought to live for at least 70 years!) and have a low reproductive rate common to K-selected species. This makes them particularly vulnerable to population pressures and slow to respond when circumstances improve. Every species seems to have something that makes it special. The kea is notorious among hikers for stealing shoelaces from boots left outside tents or radio antennae off cars. Kakapo are so unique as to need another post to do them justice. Kereru are one of the most important seed distributors for native trees. And I haven’t even mentioned kakariki, huia (a bird that was not only sexually dimorphic in appearance but also in diet! Alas, sadly extinct), kokako (a bird said to have the one of the most beautiful songs in the world) , tui, . . . .

Suffice it to say, New Zealand is still, despite the historic losses, a birder’s paradise. Concerted government-sponsored conservation efforts focusing on predator eradication and habitat protection have stemmed the tide of extinction and has led to a number of successes. New Zealand not only gives us an example of what life would have been like without mammals, it gives us hope that our efforts to conserve species are not in vain.

Author: Sarah Hearne, hearnes[at]tcd.ie, @SarahVHearne

Image Sources: Weta image from www.treknature.com.

All other images by Sarah Hearne.