- Super-Ranging: Ranging behaviour in badgers isn’t always black and white! - 15/02/2018

- Badgery Fieldwork - 22/02/2015

Sometimes a species is so well studied it is hard to believe that there is anything new to discover about them. I’ve often felt this about badgers, the subject of my PhD research. Don’t get me wrong, I love badgers and they could never bore me. Ever. But there are just so many papers already written about every facet of their lives – their social structure, their ranging behaviour, their diet, their [really cool!] reproductive biology, and of course their role in the maintenance of bovine tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium bovis infection. At this stage, what could we not know? But with advances in technology, come new discoveries!

Our latest paper in the journal PLOS ONE describes a brand new “super-ranging” behaviour in badgers, which was revealed through the long-term deployment of GPS satellite tracking collars on a population of badgers in County Wicklow, Ireland by the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) and the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

Badgers are a protected species and are one of Ireland’s most iconic wild creatures, but they can harbour TB and inadvertently transfer it to cattle. Infected cattle must be culled, which results in the loss of millions of euro each year in the agricultural sector, and can devastate farmers’ livelihoods. To date, the national control program has included annual testing of cattle, farm biosecurity measures, slaughter of infected cattle, restrictions on infected herds and, when implicated in disease transmission, culling of badgers in areas up to 2km from the affected farm. Despite all of these control measures and the significant reduction in disease prevalence in cattle and badgers since controls were implemented, bovine TB persists, albeit at very low levels.

However, DAFM recently announced it would be rolling out a national programme to vaccinate badgers as part of a continued effort to eradicate TB. Vaccinating badgers against TB provides an excellent opportunity to break the cycle of disease transmission between cattle and badgers. Yet for a vaccination strategy to be effective, it is imperative that we understand how badgers move around their environment, and that we target those individuals most likely to spread disease.

Our badger project was conceived by DAFM and NPWS in order to look at the ranging behaviour of badgers in relation to a large road construction project. A 16km stretch of the N11 was due to be upgraded to brand new M11 motorway. Our objective was to see if an environmental disruption of this scale would alter the badgers’ normal ranging behaviour. It is widely believed that in areas adjacent to major road-builds, TB breakdowns in cattle herds would be exacerbated. The thinking is that the badgers, having been disturbed by the roadworks, would move around more, in turn facilitating the spread of TB. The main objective of my research is to see if badgers do in fact move around more in response to roadworks (keep your eyes peeled for another post in the near future!). Finding out the answer involved putting GPS tracking collars on 80 badgers over the course of nearly seven years (April 2010 – August 2016). This timescale covered a period before the roadworks started, during the roadworks themselves and continued for a year after the new motorway opened.

Badgers live in social groups and each social group has a territory. Normally, badgers don’t venture too far beyond the boundaries of their territories. These boundaries sometimes last for decades, and are clearly marked at the borders by latrines. Individuals may actively defend these territories if others intrude. The organisation of badgers into social groups helps mitigate against the spread of TB, because territory boundaries serve to limit contact between individuals, meaning the disease doesn’t spread as easily. However, when there is movement between neighbouring social groups, an associated increase in disease prevalence in those groups has been observed.

As the GPS data started to roll in, we could see that most of the badgers were behaving as expected. Everyone in the same social group used the same areas, generally respecting the territory boundaries.

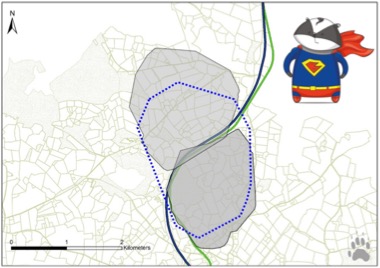

However, we soon spotted something unexpected. We discovered that some male badgers completely ignored these traditional territory boundaries, and instead ranged far into areas that encompass the territories of other social groups as well. Their home ranges were between two and three times larger than was typical for other badgers in their social group. We called these badgers “super-rangers”.

Classically, a home range is defined as the area traversed by an animal in its normal activities of gathering food, mating and caring for its young, and occasional excursions outside of this area are not considered part of the home range. The movement patterns we were seeing were not those of badgers making occasional excursions outside of the group’s territory, but rather they were of badgers that were holding greatly enlarged territories, sometimes for several years. We are still not sure why super-rangers behave like this (GPS data can only tell us where they are, not what they are doing), but it may be that they gain access to a greater number of female badgers than if they were to stay at home. It is possible that they are actively defending these enlarged territories, because some of our super-rangers accumulated many scars from fight wounds over time.

Super-ranging highlights many potential opportunities for disease transmission. Essentially, super-ranging further increases the number of badger-badger interactions. A super-ranger will be sharing setts with badgers from more than one social group. Setts are warm, humid places – ideal for disease transmission, e.g. through coughing or sneezing, as TB is primarily transmitted through the air. Super-rangers will be defending their large territories either by marking at latrines or through fighting. Bite-wounds, which they get through fighting, are the second most important route of TB transmission in badgers. Contaminated latrines provide opportunities for indirect transmission of disease – both to other badgers who also use these latrines, and to cattle grazing in pastures containing latrines.

Super-rangers may also be physiologically stressed (it must be hard work holding a such a large territory!). Stress has implications for the progression of disease, with stressed individuals shedding more M. bovis bacteria into the environment. Super-rangers may be key players in the maintenance of TB in the badger population by facilitating spread between different social groups. This discovery is not bad news for badgers, quite the opposite! If these individuals can be vaccinated, ideally when they are young and before they start to super-range, it could meaningfully contribute to the eradication of bovine TB in Ireland.

This research is exciting to me for three reasons. Firstly, it demonstrates that there are still new discoveries to be made, even in such a well-studied species! Secondly, it fundamentally alters our understanding of badger ecology, revealing the existence of two alternative ranging strategies by male badgers in a single population. Finally, by better understanding how badgers move around their environment, we can pinpoint where the greater risks for TB transmission lie and which individuals are most likely to be spreading the disease. This is extremely valuable information from a disease control perspective. Our research on badger movement should help to maximise the efficiency and effectiveness of the impending badger vaccination programme, which is great news. From both conservation and disease-control perspectives, a well-designed vaccination programme should provide a win-win situation.

To find out more, read our PLOS ONE article ‘Super-ranging. A new ranging strategy in European badgers’.

Other good stuff:

You can watch a short video about this research here.

To find out more about the DAFM/NPWS project and our badgers, you can watch “Living The Wildlife” with Colin Stafford-Johnson here.

You can read an earlier blog post I wrote about the joys of fieldwork here.

______________

About the Author

Aoibheann Gaughran (holding Tiffin) is a final-year PhD student in Prof. Nicola Marples’ research group in the Department of Zoology, Trinity College Dublin. Her research focuses on the movement ecology of the European badger and is funded by and in collaboration with the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine and the National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Website | TCD Zoology Profile

Twitter | @Aoibh_G