Ever since the observations of Aristotle, said to be the earliest works of Western biology, we have endeavoured to understand the workings of the natural world. But the modern scientific method is a relative latecomer on this scene, and it is fascinating and humbling to see the many creative ways in which we have managed to get it wrong over the years. Modern zoology, ancient zoology, and medieval zoology are all part of the same weird and wonderful phylogenetic tree.

Before there were peer-reviewed journals, there were bestiaries, medieval books that described the world’s animals as Europeans of the time understood them. Before there were Zoology Departments, zoologists (or the closest thing that existed at the time) would put forth ideas that seem ridiculous today. Three of their best theories are collected below.

Theory #1: Shrews Are Evil

The “ravening beast” known as the Pygmy Shrew, or Sorex minutus. By polandeze on Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

The “ravening beast” known as the Pygmy Shrew, or Sorex minutus. By polandeze on Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

The Taming of the Shrew is one most Shakespeare’s best known comedies, telling the story of a relationship between Petruchio and Katheria, who is known as a “shrew” for her stubborn and bad-tempered nature. To this day, the word “shrewish” is still used to say that a woman has these characteristics.

Apart from the misogyny of labelling women this way, it seems strange to us now that innocuous little shrews would be the animal to compare them to. Who could look at a tiny pygmy shrew (Sorex minutus), eating spiders and woodlice because it’s too small to take on an earthworm, and see anything aggressive or disagreeable? Strange as it may seem, for centuries the shrew had a reputation as not just disagreeable but downright evil, as Edward Topsell expounded in The History of Four-footed Beasts in 1607:

It is a ravening beast, feigning itself gentle and tame, but being touched it biteth deep, and poisoneth deadly. It beareth a cruel mind, desiring to hurt anything, neither is there any creature it loveth.

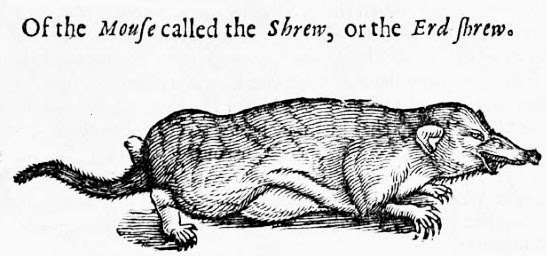

A decidedly more sinister looking shrew, illustrated in the 1658 edition of Topsell’s work. (Public Domain)

A decidedly more sinister looking shrew, illustrated in the 1658 edition of Topsell’s work. (Public Domain)

Shrews may look cute, but according to Topsell this is a cunning ruse: the shrew is waiting for you to touch it, and when you do it will bite you and kill you with its deadly poison. The idea that shrews are dangerous and poisonous goes back as far as the Roman Empire and Pliny the Elder. Though he might have been editorialising slightly on the shrew’s malicious nature, Topsell and his forebears were not entirely wrong about the poison: it is now understood that certain shrew species are indeed among the world’s only venomous mammals. This was not understood until the 1940s, when experiment involving the American short-tailed shrew Blarina showed that its sub-maxillary tissue produced venom strong enough to kill a cat. The same paper contains an account of a shrew biting a man’s hand and causing burning, swelling, and shooting pains for more than a week, without any bacterial infection.

So a small, fluffy animal like a shrew can produce harmful venom. In previous ages people took this as a sign of the shrew’s scheming, evil nature. Today, zoologists do not generally consider species to be good or evil, but might still advise people not to go around touching shrews.

Theory #2: Geese and Barnacles Could be the Same Thing

In fairness, the resemblance is uncanny. Goose Barnacle by Hans Hillewaert from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0), Barnacle Goose Public Domain

In fairness, the resemblance is uncanny. Goose Barnacle by Hans Hillewaert from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0), Barnacle Goose Public Domain

Migration is one of the wonders of animal behaviour. The Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea) is known to travel up to 96,000 km in a year, wending its way between the Arctic and Antarctica and back. Somehow, Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) are able to make multi-generational odysseys across North America, with offspring continuing the same journey on which their eggs were laid. When migration can still seem so bewildering to us today, it is small wonder that it presented an almost ineffable mystery to people in times past, with the most outlandish theories being accepted to explain why certain animals would appear and disappear at certain times of year.

One such theory involved the Goose Barnacle (Lepas anserifera). This widespread crustacean is commonly found on driftwood washed up on the beaches of Ireland and other European countries. In the 12th century, Gerald of Wales wrote the Topographia Hibernica, an account of the recently conquered Ireland which informed foreign opinion on the country for centuries. The Barnacle Goose (Branta leucopsis) was among the bizarre Irish creatures he described:

There are likewise here many birds called barnacles, which nature produces in a wonderful manner … Being at first gummy excrescences from pine-beams floating on the waters, and then enclosed in shells to secure their free growth, they hang by their beaks, like seaweeds attached to the timber. Being in process of time well covered with feathers, they either fall into the water or take their flight in the free air, their nourishment and growth being supplied, while they are bred in this very unaccountable and curious manner, from the juices of the wood in the sea-water. I have often seen with my own eyes more than a thousand minute embryos of birds of this species on the seashore, hanging from one piece of timber, covered with shells, and already formed.

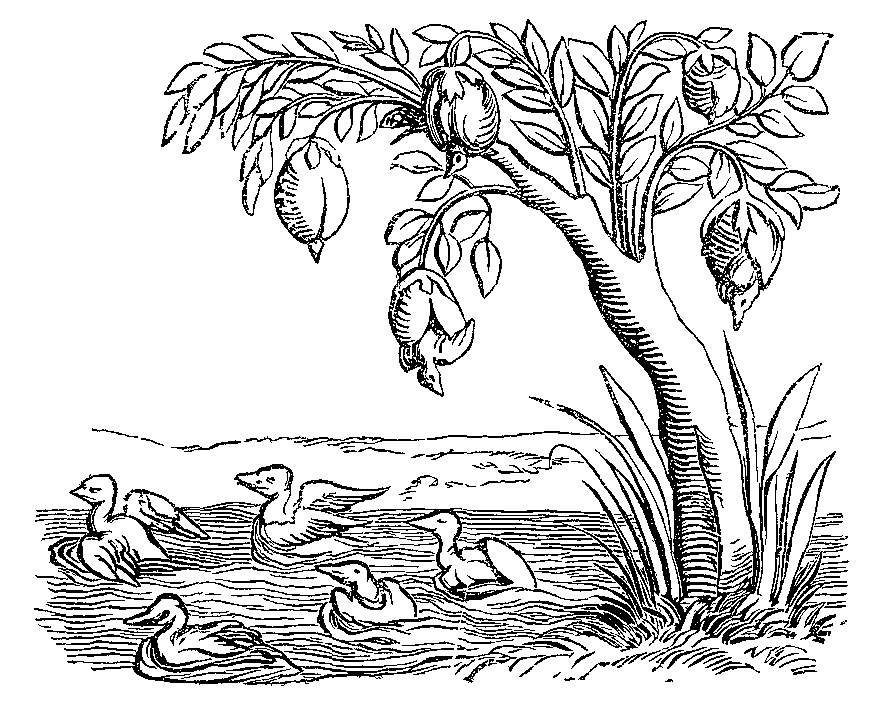

Gerald of Wales was not the only one who thought geese grew from barnacles on wood. This illustration from Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia (1544) shows geese emerging from barnacles on a tree. (Public Domain)

Gerald of Wales was not the only one who thought geese grew from barnacles on wood. This illustration from Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia (1544) shows geese emerging from barnacles on a tree. (Public Domain)

According to Gerald, Irish Catholics were happy to eat these geese on Fridays, as they were “not born of flesh”. It is worth noting that Topographia Hibernica was a work of propaganda, as well as a purported scientific account. Gerald of Wales was writing shortly after the Norman invasion of Ireland, and dedicated his work to King Henry II. His thoughts on Ireland’s animals can be compared with his passages on Ireland’s people:

The Irish are a rude people, subsisting on the produce of their cattle only, and living themselves like beasts.

…

This people then, is truly barbarous … indeed, all their habits are barbarisms. … excluded from civilised nations, they learn nothing and practise nothing, but the barbarism in which they are born and bred and which sticks to them like a second nature. Whatever natural gifts they possess are excellent, in whatever requires industry they are worthless.

A “Barbarous” Irish kingship ceremony, as depicted by Gerald of Wales. The “brute” of a king bathes in broth made of a slaughtered mare’s flesh, which he and his courtiers eat and drink. (public domain)

A “Barbarous” Irish kingship ceremony, as depicted by Gerald of Wales. The “brute” of a king bathes in broth made of a slaughtered mare’s flesh, which he and his courtiers eat and drink. (public domain)

In the 16th century, geese were still depicted emerging from barnacles, as seen in Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia, though he thought a “goose tree” on the water’s edge was more likely than Gerald’s idea of geese growing on a floating log. As late as the 17th century, it was proposed that birds travel to the moon and back, sleeping for most of the 60-day journey and surviving on their fat stores.

It took until the classification of Carl Linnaeus to show us that barnacles, trees, and geese are from very different categories of organism and aren’t related in this way. With Darwin and Wallace, we finally saw how they were related.

Theory #3: Pelicans Stab Themselves to Feed Their Young

Mosaic in Althofen Church, Austria, depicting the mother pelican “in her piety”. (Public Domain)

Anyone who’s ever donated blood in Ireland will have seen the logo of the Irish Blood Transfusion Service. The outline of the logo is obviously shaped like a drop of blood, but you need to look quite closely to see that it also contains a stylised pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus). The IBTS even gives out an award called the Porcelain Pelican to people who give blood 100 times.

This is a reference to an odd and slightly ghoulish idea from the old bestiaries, that the mother pelican feeds her young with the blood from her own breast. Supposedly, she would stab herself with her beak and let the chicks drink her blood, to keep them alive when other food was unavailable.

This act of selflessness earned the pelican a place as a Christian symbol, as seen when Thomas Aquinas calls Jesus a pelican in his hymn Adoro te Devote:

Lord Jesus, Good Pelican,

wash my filthiness and clean me with Your Blood,

One drop of which can free

the entire world of all its sins.

In modern zoology, birds are well known for their widespread and devoted parental care, but no bird species is known to feed its offspring on its own blood. Medieval zoology experts looking for a symbolic self-sacrificing aquatic bird may have been better served by the Eider, which does pluck its own downy feathers to line its nest. Eiderdown is so soft and warm that people will sell duvets and pillows filled with it for thousands of Euro.

The myth of the self-harming pelican may have originated with the sight of pelicans using their long bills for preening. Photo by Dezidor on Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)

The myth of the self-harming pelican may have originated with the sight of pelicans using their long bills for preening. Photo by Dezidor on Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)

Our understanding of the natural world has come a long way since the Medieval period, now that Zoology is a modern scientific discipline. But we should not feel too smug about the fact that our forebears believed in evil shrews and saintly pelicans. Many myths about animals are still widespread, and some native animals still have undeserved reputations for ferociousness. How many times have you heard the one about the badger biting a person’s leg until they hear the bone snap, or the swan breaking a man’s arm with its wings? See also this previous Eco Evo post on an unfounded attack on raptors and corvids in the Irish media. Both research and outreach will always be vital if we are to understand nature as fully as it deserves.

______________

About the Author

Fionn Ó Marcaigh is a PhD student in Nicola Marples’ research group in the Department of Zoology, Trinity College Dublin. He studies birds on Indonesian islands to uncover the factors underlying the evolution of new species, supported by the Irish Research Council. He has previously written for Eco Evo on animals in the Irish language. Find out more about his research here:

Website | TCD Zoology Profile

Twitter | @Scaladoir

Research Gate | Profile

LinkedIn | Profile

I’v never seen that Shrews before