- The socio-economic theory of animal abundance - 01/04/2021

- Home and Away: Australian expats - 13/12/2019

- Home and Away: Monotreme mistakes - 22/11/2019

Natural history museum collections are invaluable snapshots of history. Research collections are snapshots of the animals and plants collected in history. Research collections are also a reflection of the people and attitudes at the time it was curated. There is a well-represented collection of native Australian animals in the Zoology Museum at Trinity College Dublin. Well-represented in many sense of the word. This is a story about the red land down under, Australia, the collection of Australian animals held in overseas museums around the world. It is a story in parts. This is the first part.

Would a Rosella by any other name smell as sweet?[efn_note] Rosellas, an endemic Australian bird in the Order Psittaciformes, was named by European settlers after Rose Hill (now Paramatta), New South Wales[/efn_note]

This story traces its roots to the day that Europeans invaded Australia, but we will start with the Saturday the 26th October 2019. For most of the world, Saturday was not a particularly notable day. It was the beginning of the Bank Holiday long weekend here in Ireland; I enjoyed a walkabout through the local park. But as the sun dawned on Uluru in the Northern Territories, Australia, it was the start of a historic day.

Uluru, a UNESCO world heritage site, was permanently closed to would-be climbers at 4pm on the 25th October 2019. Until then, climbing Uluru was discouraged by Parks Australia and the Anangu traditional owners, who jointly manage Uluru-Kata Tjuṯa National Park, but was not illegal. Climbing Uluru violated the ancient cultural and spiritual traditions of the Anangu that underpin Uluru’s significance. The Anangu traditional owners campaigned for 34 years to close Uluru out of respect to their traditions. There are also preservation and safely concerns associated with climbing but that is another story. Closing Uluru is significant because it marks a positive outcome for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders rights in a long history of oppression and abuse in Australia’s colonialist history.

But what does Uluru have to do with dead animals in European museums? The clue lies in the name. The rock formation has always been called Uluru, which comes from the Pitjantjatjara language, by the traditional owners, but between 1873 and 1993, the rock formation was officially called Ayer’s Rock; named by William Gosse after the Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers. Renaming locations, plants and animals with European-centric names is a story repeated many times in Australia. In many instances, the original indigenous name has been lost. A notable exception is the kangaroo, which derives from the Guugu Yimithirr word gangurru. In old museum collections, particularly displays that have not been updated recently, specimens are referred to the name given by European colonisers and not the local indigenous name or the ones in current vernacular use.

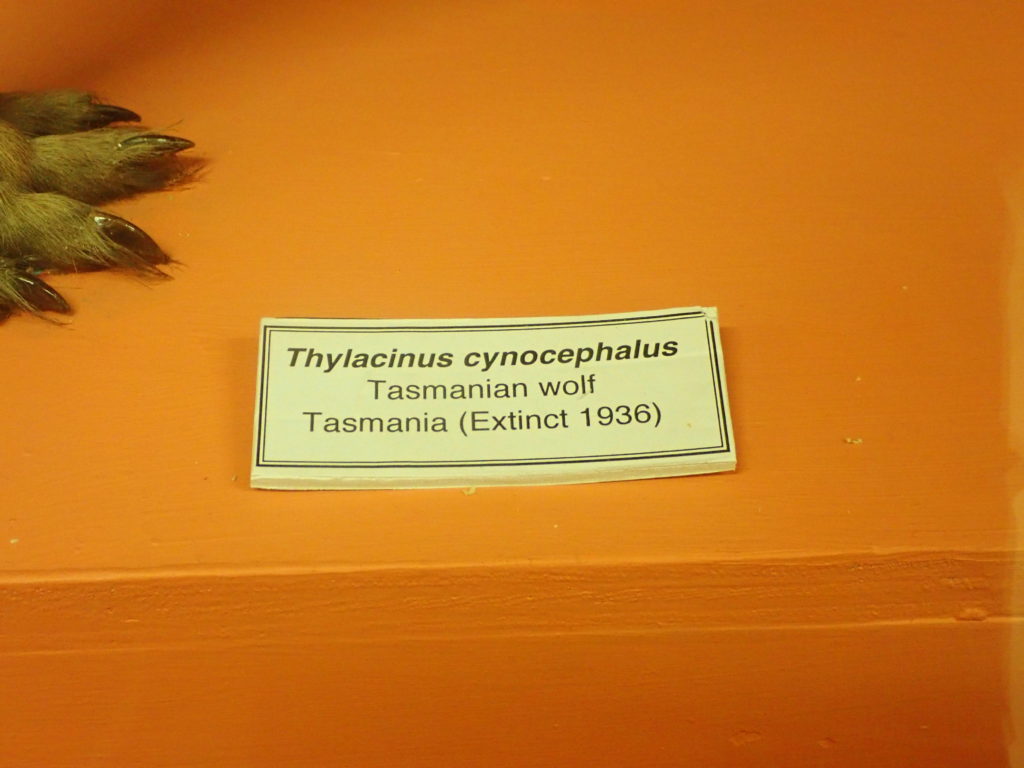

The Zoology Museum[efn_note] As an aside, the name provided with the Zoology Museum’s thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) is Tasmanian wolf, arguably a less common or exciting name than Tasmanian tiger, another European vernacular name for the thylacine. Since thylacines are neither tigers nor wolves, the name thylacine is considered to be more accurate than the alternatives. Thylacine actually derives from the Greek word thýlakos, meaning “pouch”. Same goes for “Koala Bear”.[/efn_note] has a taxidermied eastern quoll (Dasyurus viverrinus) on display. The eastern quoll is an endangered carnivorous marsupial, whose current threats include loss of habitat, predation by invasive European mammals (cats and foxes) and the spread of poisonous cane toads (Rhinella marina). Quoll derives from the indigenous name dhigul from the Guugu Yimithirr language and was recorded as such by early European explorers (Joseph Banks, after whom the iconic Australian genus of plants Banksia are named). Quolls are about the size of a cat which lead them to being called the native cat at some point, replacing quoll as the vernacular name. Native cat is the name provided with the specimen in the Zoology Museum, but it is not the name most commonly used today. The call to change the vernacular name back to quoll came in the 1960s by naturalist David Fleay. One could say there’s no need to call it by a colonialist name since it already has a quality name.

The same can be said for the kākāpō (Strigops habroptilus) in the Museum that is labelled as night parrot. Kākāpō, an endemic flightless bird from New Zealand, means night parrot in Maori, the language of indigenous New Zealanders, and is the current vernacular name. Kākāpō, also written without the accents, is a great name. Better than night parrot. Kākāpō are critically endangered, having been decimated by introduced European mammals, like stoats, cats and rats, as well as general threats like land clearing and hunting. The common names for birds are an unusual example in taxonomy and systematics because it is arguably the most standardised than other taxa and ornithologists are very particular about the names of birds. [efn_note] https://www.worldbirdnames.org/english-names/principles/ [/efn_note] Official lists are maintained, and proposed names need to be vetted and approved.

Arguably, referring to specimens by their European name instead of their indigenous name is a relic of imperialist and colonial attitudes; something we as a global society should be moving away from. A more forward-thinking reason to use indigenous names is that using traditional or indigenous names in vernacular language brings indigenous language into mainstream society that has otherwise discriminated against its use. To this end, plants and animals are fruitful base from which to learn indigenous culture.

Increasing indigenous awareness does not mean completely replacing vernacular names. Awareness can be achieved by simply knowing what local mobs (a term for the resident indigenous groups) called common species. The University of Melbourne’s Research Unit for Indigenous Language’s [efn_note] https://arts.unimelb.edu.au/research-unit-for-indigenous-language/ [/efn_note] ‘word posts’ project is a good example of raising community awareness by posting examples of nouns, including animals, in different indigenous languages. Many botanical gardens in Australia have a collection of edible or medicinal plants that would have been used by the local mobs and often offer cultural tours and experiences led by local indigenous guides.

The idea of rebranding Australian animals or re-evaluating Australian’s natural history through post-colonialist views is not new. Many authors have discussed the topic in more depth than I have here. A challenge for introducing indigenous names for Australian animals is deciding which name to use. There were over 250 indigenous languages in Australia prior to European settlement, of which only 13 remain taught today[efn_note] http://theconversation.com/the-state-of-australias-indigenous-languages-and-how-we-can-help-people-speak-them-more-often-109662 [/efn_note], and all had different names for the same species.

Since 1993, Uluru has been gazetted as “Uluru/Ayer’s Rock”. Most Australians will preferentially use Uluru over Ayer’s Rock. Out of respect for indigenous communities and with a better, more accepting, global society in mind, I suggest we all do the same for animals and plants when a widely accepted indigenous alternative is available, regardless of where we are in the world. Given Australia’s recent track record for human rights, it’s the least we Australians can do.

Dr Jacinta Kong is a teaching and research fellow in the Department of Zoology at Trinity College Dublin. She is a first generation Australian expat from a refugee family who has personally experienced the end of the British Empire. She has not climbed Uluru and never will.