- How Being Obvious Can Make You Discrete - 15/12/2020

Camouflage is all about staying hidden. Hiding is useful for animals because they’re less likely to get eaten – or are better able to sneak up on prey! So why do some animals display “flash behaviour”, making them temporarily more obvious and undermining their camouflage?

Flash behaviour describes when a normally cryptic animal reveals a hidden patch of colour or produces a noise following a disturbance, and then returns to a cryptic state. This is seen in many animal groups such as insects, even-toed ungulates (hoofed animals), frogs, and rabbits. Flash behaviour can be continuous – e.g. red-winged grasshoppers reveal colourful wings in flight but are camouflaged when wings are folded – or intermittent – e.g. black-tailed jackrabbits reveal and wag their conspicuous black tails several times when fleeing before curling it back up.

There are two main hypotheses to explain the evolution of flash behaviour: the first is that flash behaviour is employed to startle a predator, the second is that it makes an animal harder to track. The authors of Flash behaviour increases prey survival (Loeffler-Henry et al. 2018) tested the second, exploring how continuous and intermittent flash colouration affected predators’ ability to search for moving prey.

The Experiment

The researchers in this experiment suggest that “flash colours are the most salient feature of prey during fleeing, thus making predators perceive prey to be of a completely different colour than their resting colour” and therefore struggle to find the prey if the flash colour is not visible. To test their hypothesis, the researchers used human “predators” searching for computer-simulated “prey”.

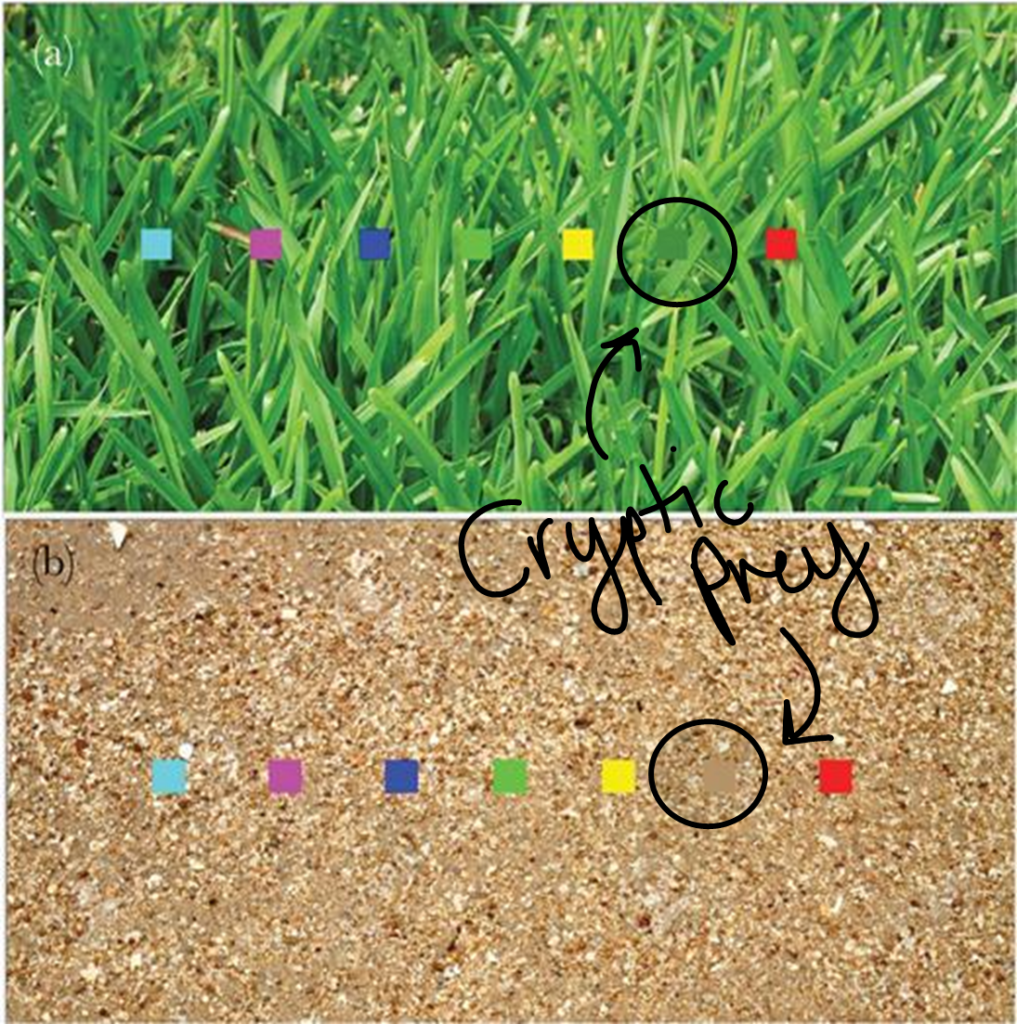

Volunteers were trained to search for “prey” (represented by coloured squares) on a screen with either a grass or sand background. When the simulation was run the prey would move across the screen via a random series of movements as the volunteer watched. The prey would then “escape” to a second screen and hide, and the volunteer would have to move to this second screen to find the (now motionless) prey in random location on the same background. Sometimes the prey would not be present on this second screen (to simulate prey escaping e.g. below ground) and so there was an option for volunteers to “give up”.

During training, volunteers searched for obvious prey, but in the final two trials they were presented with cryptic prey. As the prey moved across the screen they either kept their cryptic colour or they presented flash behaviour – simulated by flickering or continuous red colour. On escaping to the second screen, the prey would then once again appear cryptic and the volunteers would attempt to find them. If flash behaviour confused the predator, then prey that presented flash behaviour while moving on the first screen should be harder to find on the second screen than prey that stayed cryptic while moving.

The Results

The results from the simulations supported the researchers’ hypothesis that colour-flash behaviour gives predators “false information” about the appearance of their prey. Volunteers’ ability to detect the prey was higher for those who experienced the consistently cryptic prey first (so were used to searching for cryptic prey), and prey which employed flash behaviour had an improved survival rate of 20% over prey without flash behaviour. There was no significant difference between the continuous or intermittent flash behaviours (i.e. both methods are equally good at confusing predators).

The results also suggests that the behaviour lowers the predator’s expectations of finding the prey. Volunteers that did not see a red square on the second screen immediately after watching prey express flash behaviour they were quicker to click “give up” than volunteers that had only been looking for cryptic prey.

The experimental design used here is obviously very unrealistic. One improvement I would suggest would be to introduce a time limit to identify the prey. In the wild an animal would not have an unlimited amount of time to search for prey; it can’t waste time searching for cryptic prey for exceedingly long periods. I also believe that more organically shaped prey would aid the results of this study, animals are rarely as geometrically shaped as a square, and I think it would be harder (and more realistic) to try spot an irregularly shaped blob on the complex background, even if the shape was uniform in every trial. Nevertheless, this study provides good evidence to support the hypothesis that flash behaviour is evolutionarily advantageous for its effects as an anti-predatory mechanism.

This study was particularly fascinating as I was unaware of the existence of flash behaviour and would not have expected that a cryptic animal revealing itself in the presence of a predator would increase its survival. In fact, I would probably have expected the contrary. Bright colours and noises used to startle, or signal predators are common across animal kingdom, however I would not have thought they were characteristics found often in cryptic animals.

Citations

Karl Loeffler-Henry, Changku Kang, Yolanda Yip, Tim Caro, Thomas N Sherratt, Flash behavior increases prey survival, Behavioral Ecology, Volume 29, Issue 3, May/June 2018, Pages 528–533, https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/ary030