- The remarkable bird life of the Wakatobi Islands, SE Sulawesi: hidden endemism and threatened populations - 10/07/2020

- The Bird Life of Wawonii and Muna Islands Part I: biodiversity recording in understudied corners of the Wallacea region - 30/06/2020

- Comparing the biodiversity and network ecology of restoredand natural mangrove forests in the Wallacea Region. - 09/12/2019

This blog was first published on #theBOUblog. Check it out at https://www.bou.org.uk/blog-oconnell-two-new-white-eye-species-sulawesi/

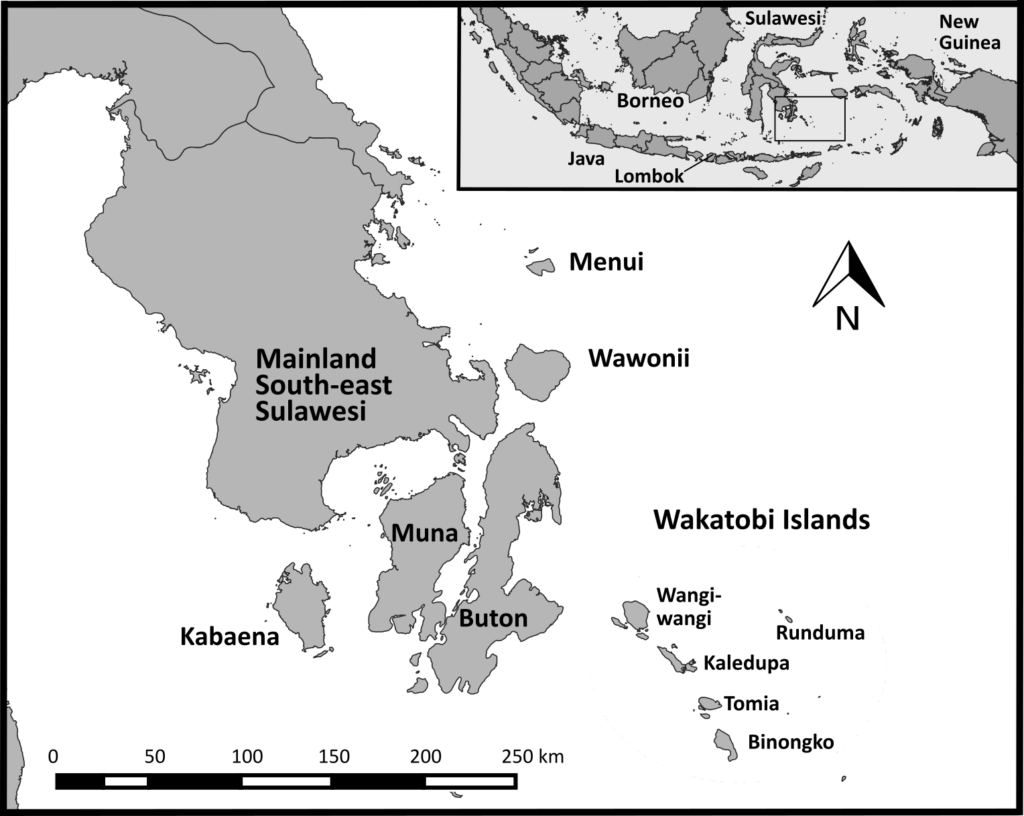

The Wallacea region has always been known to be home to many unique species, with birds of paradise, giant reptiles and marsupial versions of sloths found among its many islands! The region takes its name from Alfred Russel Wallace, who along with Darwin, developed the theory of evolution from his studies of the species of Wallacea. When I first set my heart on a career as a Zoologist (a decision made with absolute certainty at age 12!) I dreamed of following in the footsteps of these great naturalists. So it is of no surprise that when I finally got around to starting my PhD many years later, I chose to study speciation (the formation of new species during the course of evolution) in the birds of Wallacea, with the hope the region still held mysteries to uncover. Our research focused on South-east Sulawesi, Indonesia. Sulawesi is a weird and wonderful part of the world, and island hopping through that region has provided me with a lifetime of unforgettable memories. It also allowed me to fulfill my dream, as in our recent paper in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, we describe two new bird species from the Wakatobi Islands, an island chain off South-east Sulawesi (Figure 1).

Header photo: Wangi-wangi White-eye © James Eaton

The Wakatobi Islands are an oceanic archipelago that have never been attached to mainland Sulawesi. Until the Trinity College Dublin (TCD) bird group lead by Prof Nicola Marples and Dr David Kelly began working on the Wakatobi Islands with collaborators from Halu Oleo University (UHO), the Wakatobi Islands had been largely ignored by the scientific community since the early 20th century. The TCD/UHO team found that the islands were home to many bird populations which seemed very different to their relatives on mainland Sulawesi. They trapped birds using mist nets to take measurements of their body size and a few flank feathers for genetic samples, before releasing the birds again. This resulted in Kelly et al. (2014) proposing a new species for the Wakatobi Islands, the Wakatobi Flowerpecker. However, this was not the only unique population, as Prof Marples and Dr Kelly’s attention was also drawn to the white-eye (Zosterops) species of the Wakatobi Islands.

The white-eyes are an incredible group of birds which are among the fastest evolving of all vertebrates, earning them a title as amongst the “great speciators” (Moyle et al., 2009). The name for white-eyes in Bahasa Indonesia is burung kacamata, which literally means “spectacled birds”. It’s an apt description, as the little white ring around their eyes gives them a quizzical bespectacled look. The Wakatobi Islands were thought to be home to a subspecies of the Lemon-bellied White-eye (Zosterops chloris flavissimus). When Prof Marples and Dr Kelly visited the Wakatobi Islands in 2003, they noted that the Lemon-bellied White-eyes there were distinctly different from the ones on the mainland, being far yellower and smaller in size. They also found a mystery white-eye only on the northernmost Wakatobi Island, Wangi-wangi, with a large yellow bill and a white chest, which was unknown to science.

These intriguing populations became one of the main focuses for my PhD work and provided me with some remarkable findings. The Wakatobi subspecies of the Lemon-bellied White-eye was distinctly different from other populations of this species in its genetics, body size, and song. The difference in song is particularly important as this is how birds find their mates, so if populations are singing differently they won’t breed and so stay separate. The Wakatobi population has been separate from any other Lemon-bellied White-eye population for at least 400-800,000 years. Therefore we propose it is recognised as a unique species, the Wakatobi White-eye (Zosterops flavissimus). Even more incredibly, I discovered that the mystery white-eye found only on Wangi-wangi Island was a completely novel species, completely genetically distinct, whose closest relatives were found more than >3000 km east of there in the Solomon Islands. We name this species the Wangi-wangi White-eye. Finding such a novel vertebrate species is extremely rare in modern times. The Wangi-wangi White-eye’s only home is a tiny (155 km2) island with a high-density human population, so urgent action is likely needed to ensure the protection of this novel species.

As well as the excitement of finding such photogenic new bird species, this discovery may have important implications for the conservation of biodiversity in Sulawesi! As resources for conservation are always limited conservation organisations prioritise their funding for designated areas which are home to the most unique and rare species. One such designation is the BirdLife International Endemic Bird Areas. In order to be recognised as an Endemic Bird Area, a region needs to be home to two species entirely restricted to that area. The recognition of two new white-eye species (along with the Wakatobi Flowerpecker) should make a strong case that the Wakatobi Islands be recognised an Endemic Bird Area and receive greater support from BirdLife International for conservation efforts on the islands. The Wakatobi Islands have experienced a massive increase in human population, so all habitats on the islands have been badly damaged. Urgent action is needed to protect the remaining habitats on these islands to protect the Wakatobi’s unique bird species. Doing so will also have knock-on benefits for other species found on the islands, such as the Critically Endangered Yellow-crested Cockatoo (Cacatua sulphurea). We hope that our work will help highlight the biodiversity of the Wakatobi Islands and wider Sulawesi region, and ensure it is protected as the world faces a looming extinction crisis. TCD and Halu Oleo University are determined to continue to work hard to ensure that some of the stunning wild areas of this region remain intact, and its unique species are recognised!

To find out more read our Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society paper here:

O’Connell, D.P., Kelly, D.J., Lawless, N., O’Brien, K., Ó Marcaigh, F., Karya, A., Analuddin, K. and Marples, N.M. (2019) A sympatric pair of undescribed white-eye species (Aves: Zosteropidae: Zosterops) with very different origins. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz022

References

Kelly, S. B. A., Kelly, D. J., Cooper, N., Bahrun, A., Analuddin, K., and Marples, N. M. (2014). Molecular and phenotypic data support the recognition of the Wakatobi Flowerpecker (Dicaeum kuehni) from the unique and understudied Sulawesi region. PLoS ONE 9, e98694.

Moyle, R. G., Filardi, C. E., Smith, C. E., & Diamond, J. (2009). Explosive Pleistocene diversification and hemispheric expansion of a “great speciator”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(6), 1863-1868.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to TCD, Halu Oleo University and Operation Wallacea for facilitating, planning and providing logistical support for this research. A big thanks to Kementerian Riset Teknologi Dan Pendidikan Tinggi (RISTEKDIKTI) for providing the necessary permits and approvals for this study (0143/SlP/FRP/SM/Vll/2010, 278/SlP/FRP/SM/Vll/2012, 279/SIP/FRP/SM/VIII/2012, 174/SIP/FRP/E5/Dit.KI/V/2016, 159/SIP/FRP/E5/Fit.KIVII/2017 and 160/SIP/FRP/E5/Fit.KIVII/2017). Finally, we like to thank all of the research assistants who contributed across many field seasons.

Other posts from the Sulawesi Birds project:

- Battle of the sexes – Niche contraction in females but not males in high density island populations by Darren O’Connell, 2019

- Kingfisher Evolution in the Wallacea Region by Darren O’Connell, 2018

- The Avifauna of Kabaena Island by Darren O’Connell, 2018

- Delicious Cuscus by Darren O’Connell, 2018

- Range extension for the Dwarf Sparrowhawk by Darren O’Connell, 2018

- The Wakatobi Flowerpecker: the reclassification of a bird species and why it matters by Seán Kelly, 2014

- Sulawesi Bird Expedition 2013 by Seán Kelly

- Sulawesi Field Report 2012 by Seán Kelly