- The remarkable bird life of the Wakatobi Islands, SE Sulawesi: hidden endemism and threatened populations - 10/07/2020

- The Bird Life of Wawonii and Muna Islands Part I: biodiversity recording in understudied corners of the Wallacea region - 30/06/2020

- Comparing the biodiversity and network ecology of restoredand natural mangrove forests in the Wallacea Region. - 09/12/2019

With Indonesia I’ve always felt like I’m just scraping the surface. Even after five field seasons in that incredible country I feel I’m always just finding further questions. One of my favourite bits was just driving around to new sites and travelling to different islands. There are always feats of incredible daring to observe (just piloting a car on a rural road takes nerves of steel), and engineering marvels and follies cut out of rainforest or carved from the hills. Any local leader could seemingly achieve anything with sufficient ambition, the consequences of which could really go either way! Easy explanations are usually not forthcoming. It is a culture where much is left unsaid, where one must ask the correct question the correct way to receive an answer. Perhaps it is this sense of mystery that keeps me coming back year after year, with each new island a world in itself.

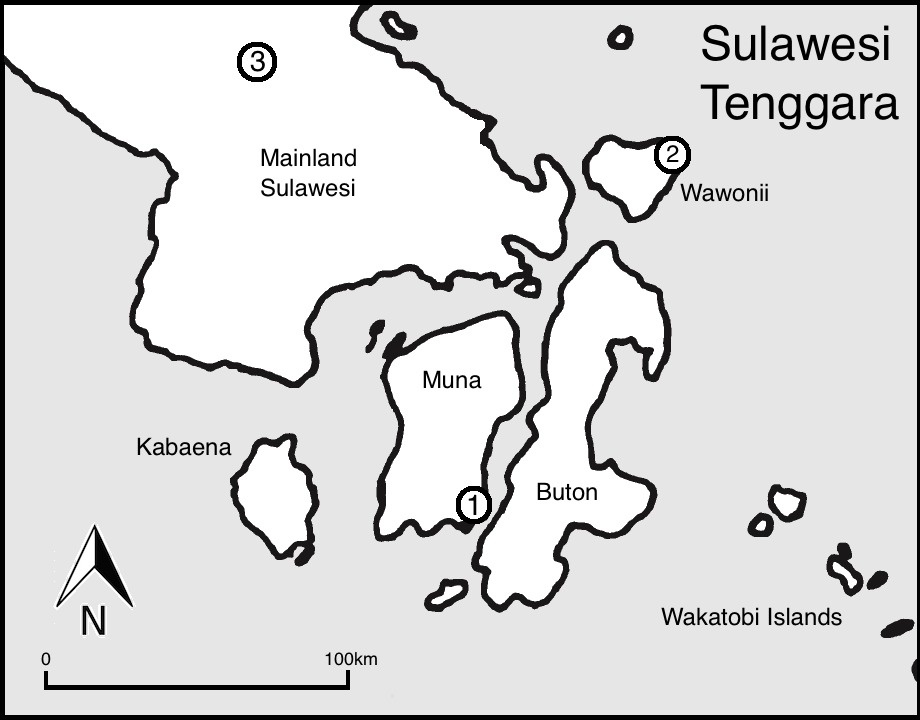

For my PhD I had the chance to island hop around South-east Sulawesi, studying the speciation and biogeography of the birds there. My final field season in summer 2017 was the perfect example, with my first visits to the islands of Muna and Wawonii, chasing the birds of these understudied islands, and taking in their contrasting environs. The main focus of the work was the region’s small passerine birds, which meant long hours working in the field in Indonesia, using mist nets to trap birds for measurements, or taking long walks in the countryside carrying out transect surveys. So as well as our target species, we were able to carry out a full assessment of the island’s avifauna. Our survey work, published in the latest issue of Forktail, was the first assessment of the bird life of Wawonii Island, and provided the first data from Muna since the 1950s.

Our first visit to Muna Island at the start of the 2017 field season started things off in altogether uncharacteristic fashion… it was actually just quite nice. After a very genteel ferry crossing, we were greeted with a landscape of low rolling hills and stunning views of a blue, blue sea. Muna contains the lowest-lying and most fertile land in South-east Sulawesi, and is known as a prosperous centre of farming activity. Most of Muna has long been deforested and densely populated, so we were arriving not expecting much. It proved a pleasant surprise, however, and absolutely ideal for our speciation work. The landscape of low scrub and frequent abandoned farmland was packed with our main target species (white-eyes, flowerpeckers and sunbirds), providing ample opportunity for taking measurements and collecting samples. In terms of wider avian biodiversity Muna was less diverse than its neighbours (with only 59 species), but threw up some surprises. The island showed evidence of karst uplift, with ridges thrust up, usually hollowed out with caves. Along these inhospitable ridges we found slivers of Muna’s old forest, which even maintained populations of forest specialist Piping Crows and Sulawesi Pitta.

Our field season really kicked off when we travelled to Wawonii, returning to the Indonesia I loved and just about survived. Still recovering from a microbe which had thoroughly hollowed me out (and hospitalised my stalwart supervisor, who I had to leave to their fate in order to keep the work going!), the ferry to Wawonii was a reassuring return to loose chickens and mopeds lashed to every conceivable surface. Getting on and off the boat would have been familiar to anyone who has participated in that heavy metal concert rite of passage, the mosh pit “wall of death”. The unspoken rule being, the only logical way to speed things up is to push harder. Wawonii had experienced severe rains for the previous few weeks, and all roads had turned to almost unpassable muddy cesspits. I was left to again marvel at the skill of Indonesian drivers as my driver deftly rode the edges of deep ruts.

In many ways Wawonii embodied all of the most frustrating and challenging aspects of working in the Sulawesi region. Foul weather predominated, with a severe storm ripping through. Even when the weather was clear, the island’s habitats provided a constant challenge. The damaged roads and total lack of phone reception made coordination a serious headache. The locals practiced shifting agriculture, with each cassava farm being planted with coconuts once the soil was exhausted. This led to a mono-culture coconut ring around the outside of the island, with very little animal diversity. Our fieldwork soundtrack was a consistent dull boom of falling coconuts. This quickly became a vaguely unnerving sound, as each of our guides could tell us of some acquaintance who’d been killed or severely hurt by a falling coconut during harvesting!

Small patches of coastal scrub and the edges of a large rice paddy provided the only opportunity to sample our target species or record any avian diversity. Here at least we found good populations of the Vulnerable Asian Woolyneck stork. Always visible on the horizon, but just out of reach, was the central forest of Wawonii. This forest is thought to be one of the few remaining intact lowland tropical forests in Sulawesi and of high biodiversity value (Canon et al., 2007), though it has never been surveyed. The heavy rains had made the paths towards it basically impassable, and after a couple of attempts defeat had to be admitted. We contented ourselves with doing what we could along the island’s fringes and enjoying the rare feeling of isolation this island provided.

Ultimately the 2017 field season provided a perfect send off to my PhD fieldwork, with excellent data collected (Muna) and that sense of adventure and challenge (definitely Wawonii!) that has kept me returning to work in Indonesia since. As the unique avifauna of these islands are increasingly threatened by habitat loss and the looming threat of large scale mining, it was a privilege to be able to highlight the biodiversity of these islands while there is still an opportunity to ensure its future.

Read part 2 of this blog series here.

To find out more read our full Forktail article: ‘The avifauna of Muna and Wawonii Islands’[efn_note]O’Connell DP, Ó Marcaigh F, O’Neill A, Griffen R, Karya A, Analuddin K, Kelly DJ and Marples NM (2019) The avifauna of Muna and Wawonii Islands, with additional records from mainland South-east Sulawesi, Indonesia. Forktail, 35: 50–56.[/efn_note].

Acknowledgements

Thanks to TCD, Halu Oleo University and Operation Wallacea for facilitating, planning and providing logistical support for this research. A big thanks to Kementerian Riset Teknologi Dan Pendidikan Tinggi (RISTEKDIKTI) for providing the necessary permits and approvals for this study (159/SIP/FRP/E5/Fit.KIVII/2017 and 160/SIP/FRP/E5/Fit.KIVII/2017). Huge thanks to the legend that is Sulaiman La Ode for achieving the killer combo of being an adept logistics operator and translator, and a top class field worker.