Last week our newest EcoEvo@TCD paper came out in PRSB (it will be Open Access soon but currently it’s behind a pay wall – feel free to email me for a copy in the meantime. Code for the multiple PGLS models can be found here). This paper is exciting for me for two reasons – firstly because the science is really cool and secondly because of how it came about. In a previous post I explained the results of the paper. Today I want to focus on how it came about.

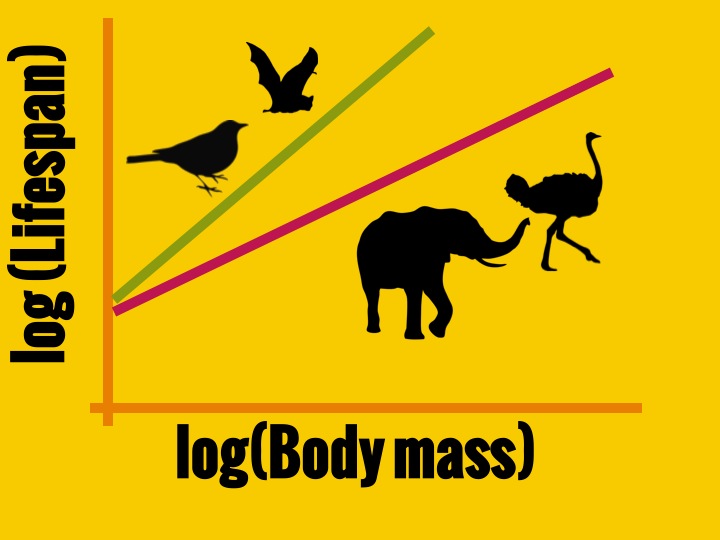

The very first seminar I think I attended when I started my job at TCD in 2012 was by Prof Emma Teeling from UCD. Emma works on bats (her research is really cool – check it out) and gave a fascinating talk about echolocation and other aspects of bat evolution. Near the end of the talk she mentioned the “exceptional lifespan” of bats, which was something I’d never heard about before. Bats live, on average, 3.5 times longer than mammals of a similar body size! Wow I thought, I wonder why…

After the talk everyone descended on our tearoom for post seminar beers and discussion. This is generally a lively event, especially when the talk is really good. It turned out that I wasn’t the only one interested in the exceptional lifespan of bats. Many of the students (notably Kevin Healy and Luke McNally) and staff (particularly Andrew Jackson) picked up on this point, and we discussed it at length with Emma and amongst ourselves.

The following week (our seminars are Friday afternoons), the discussion was still raging. Was the exceptional lifespan of bats just due to flight? Was there a way we could disentangle the effects of flight from those of phylogeny (bats are the only mammals that fly). Did statistical methods that declared “bats are special” a priori run the risk of always confirming their bias when they fitted “bat” as an extra factor in their models? [Several simulation studies later we were able to say “Yes” to this question!]. We read a few papers and talked about other things that could reduce extrinsic mortality other than flight. It was a fun couple of weeks!

Now this is the point that most ideas born in the tearoom tend to die. We come up with a set of questions, data that could be collected, papers that should be read, and then no-one comes forward to finish up. And admittedly, although we returned to the topic every now and again, we never went any further with it. Several months passed, the summer came and went, and the idea looked like it would go to the idea graveyard. However, this was also around the time we decided to start NERD club – our weekly Ecology and Evolution research groups meeting. In an attempt to find some topics that could appeal to both zoologists and botanists we brought back the lifespan question, and had an amazing cross-disciplinary discussion about it. This renewed our enthusiasm. Also it provided the perfect test of the NERD club format – could 10 authors (the number of people who expressed an interest in being involved in the project) work together to produce a coherent research paper, or would too many cooks spoil the broth?

We began by having meetings discussing ideas and coming up with clear predictions. I think this was the most important step because with so many coauthors we could easily have ended up with a huge set of variables, and a horribly unwieldy analysis and paper. We split up literature searching across all the students, and then the students summarized what they’d found. We then split the data collection across myself and several students (though a large chunk of extra data was collection by Kevin Healy in the later stages of the project), and had a group of students in charge of the figures and a group in charge of analyses. I took the lead on writing a draft (though again Kevin Healy did a large chunk of this in the later stages).

Quickly we realised that this wasn’t just going to be a paper for all of us, it was also an amazing opportunity to learn from each other about how we do things, and a great teaching opportunity. I personally come from a phylogenetic comparative methods background, and although I collaborate a lot with people from across the world, working on very different questions and very different study groups, they all come from a background where comparative thinking is standard. At TCD this wasn’t the case, so I found myself selling the idea of comparative analyses, phylogenies, and literature-based data collection to the group. In turn Andrew Jackson taught us about how he approaches statistical analyses, and Ian Donohue was invaluable in writing a snappy, jargon free abstract. All of this made the process much slower than it would have been with a smaller group, but with every mistake made collecting data, every misstep in analysis and every argument about the values of broad general answers versus accurate taxon-specific answers, we learnt as a group and improved as scientists and educators.

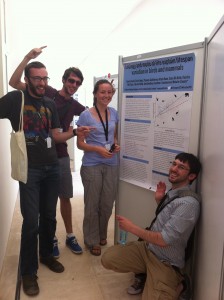

Eventually it became clear that Kevin Healy was doing the bulk of the work so he became project leader and first author, and pushed the project into its final phases. Thomas Guillerme also took a large role in writing R code and running analyses, including showing us all how to run analyses on the TCD computer clusters. Everyone helped with drafting the manuscript and we presented the work at ESEB 2013, and Evolution 2013. It was truly a group effort from start to finish and I couldn’t be more delighted with getting it published at PRSB. This is the first publication for many of the authors, and hopefully the first NERD club inspired publication of many.

So all in all it’s been two and a quarter years from the first conception of the idea to the paper finally coming out. But I think even this delay has been an amazing teaching experience – I think as PhD students you see your peers popping out papers left, right and centre, with little understanding of the effort (and the incredible amount of faffing with formatting etc!) that goes into each one. Of course we all have our “quick and dirty” (ok maybe not that dirty!) little publications, but honestly most of mine take at least 2 years. I would definitely recommend trying this in your department! It was time consuming but totally worth it. The only thing I’d change in future is that I’d have the whole project on GitHub to make collaborative coding and editing easier (we only just learned git and I’m super excited about using it next time!), and I think this would enrich the learning experience even further.

I hope this has inspired more people to try a collaborative research/teaching project. Now we just need another amazing idea so we can start our next NERD club paper…

Author: Natalie Cooper, ncooper [at] tcd.ie, @nhcooper123