- Nature and Wellbeing - 31/10/2020

- A Scientist Goes to Court - 29/01/2019

A Long Read by Cian White

For anyone living in a city during a pandemic, the benefit of parks to your physical and mental health is obvious. There is space to properly social distance, space to meet up with friends, space to exercise or kick a ball around, benches to sit on, air to breathe, life to live. Then there is the life in the parks, the trees and shrubs and birds and insects, all the stuff that comes under the vague heading of greenspace or nature. So, to celebrate World Cities day and in the interest of public health, let us explore a very interesting area of research developing at the intersection of ecology and psychology: meaningful nature experiences.

The basic premise of meaningful nature experiences is that interacting with nature can be good for your wellbeing. How good? Well, according to some, as good for your wellbeing as living in a well-off neighbourhood, being seven years younger or $10,000 richer. If we are to believe these results, encouraging interactions with nature could be the next big preventative healthcare push. Some physicians have already begun prescribing nature ‘pills’, instructing patients to spend time outdoors. Just as mindfulness has gone from a relatively obscure spiritual practice to the mainstream, (with ‘Mc’Mindfulness centres, books and apps and popping up everywhere), meaningful interactions with nature could become the posterchild of optimizers, wellness gurus and public health organisations in the late 2020s.

A (brief) literature review

To give you a feel for the area, let’s look at two recent(ish) high-profile papers: Kardin et al. 2015 and White et al. 2019, both published in Scientific Reports.

In 2015, Kardin et al. conducted an epidemiology study, collecting socio-economic, health and wellbeing data and comparing this with the density of street trees in neighbourhoods in Toronto, Canada. They examined whether the number of street trees in a neighbourhood correlated with increased health and wellbeing. The headline takeaway? Having ten street trees in a neighbourhood increased perceived health by the equivalent of being $10,000 richer or being seven years younger.

This is quite a result. The researchers statistically controlled for typical socio-economic variables (such as diet, income, age and education), so the effects of these variables are accounted for and, as Canada has universal health care insurance, they argue that these results are not as confounded by access to healthcare as in other counties such as the US.

How much should we trust this result? Well, Kardin looked at three measures of health: 1) self-reported (perceived) health, 2) a cardio metabolic condition index (an index created from summing seven variables: High Blood Glucose, Diabetes, Hypertension, High Cholesterol, Myocardial infarction (heart attack), Heart disease, Stroke, and ‘Obesity’) and 3) mental disorders index (created by summing depression, anxiety, addiction variables). From these, Kardin found significant correlations between the density of street trees and self-reported health, and the density of street trees and the cardio index, so let’s examine these results in more detail. (There was some quite complicated modelling done to analyse the data used in this paper and I am not confident to comment on how robust the methods chosen to conduct the analysis are. If anyone feels like digging through their methods, I would be interested in how confident you are in what they report!)

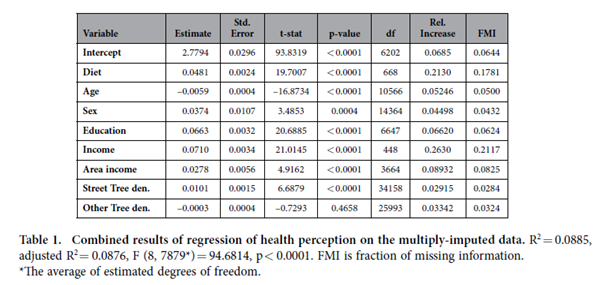

The above table outlines the result of the regression model for self-reported (perceived) health index and all the explanatory variables of interest. We can see that street tree density has a positive impact on perceived health (estimate = 0.0101) and this is significant (P<0.0001, although as they used such a large sample size – N > 30000 – significance is expected even for weak effects). Being older is associated with lower perceived health score (est. = -0.0059) while education and income have large positive effects on perceived health (est. = 0.0663 and est. = 0.0710, respectively). Putting this in context, education and income are 6.5 and 7 times more important for perceived health scores than the density of street trees in your neighbourhood.

This is nowhere near as flashy as the headline the paper reported (having ten street trees is equivalent to being 7 years younger, or $10,000 richer), but it is still quite a surprisingly strong result. For instance, I could imagine that on a per-dollar-spent basis, increasing street trees in Toronto would boost perceived health more than spending on education would (if anyone out there wants to actually do that calculation please do). Overall, the model explains 9% of the variation in the data, i.e. 91% of the variance is due to variables that aren’t contained in the model. That’s not high predictive power, yet in ecology we would be pretty happy with this for such a broadbrush effort (although I’m not familiar enough with epidemiological studies to say whether this is typical).

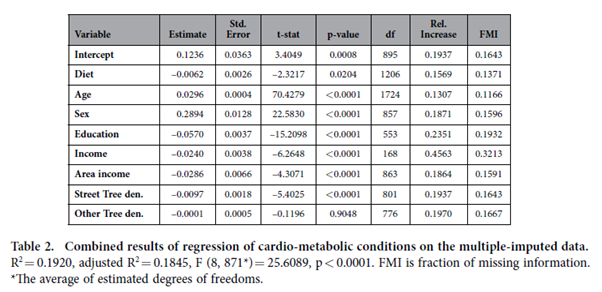

While there are a few papers showing that perceived health predicts actual health (e.g. here, here, and here), it is important to say that perceived and actual health are not the same thing, so let’s look at a real health indicator. Below is the regression table of cardio metabolic condition index and all the variables of interest is below. The density of street trees is negatively associated with the cardio metabolic condition index (est. -0.0097), meaning that as tree density increases, we would expect, on average, an individual’s cardiac health to be better. Again, education produces roughly 6 times a greater effect than street trees (education est. = -0.0570), but still within an order of magnitude of the effects of the effects of trees – I find this really quite surprising!

Overall, this is an interesting study. Does it justify public health schemes promoting street tree planting? No. At least, not yet. I would like to see this analysis replicated in other cities in different cultures, then, using those results, see how well we can predict the effect of street trees on health outcomes in cities we haven’t yet included for analysis. At the moment, this is an interesting line of research, but needs a lot more study before we can be confident that the effect is real and replicable. (But see studies which are finding similar results here, here, and here.)

The literature is quite confident that interacting with nature is good for us and researchers are now turning their attention to the quantity and quality of time spent in nature, aiming to describe a ‘dose’ of nature that has the most benefit per time spent. Enter White et al. 2019. The headline takeaway from this paper was that spending 120 minutes in nature a week is beneficial for health and wellbeing. The data came from a Natural England survey of N = 19,806, weighted to be nationally representative of England. The outcome variables of interest were self-reported physical health (single item: ‘How is your health in general?’. Response options: very bad, bad, fair, good and very good, median = good) and subjective wellbeing (single item: ’Overall, how satisfied are you with life nowadays?’ with responses ranging from ‘Not at all’, 0, to ‘Completely’, 10, median = 8). These two self-report measures were then correlated with time spent in nature.

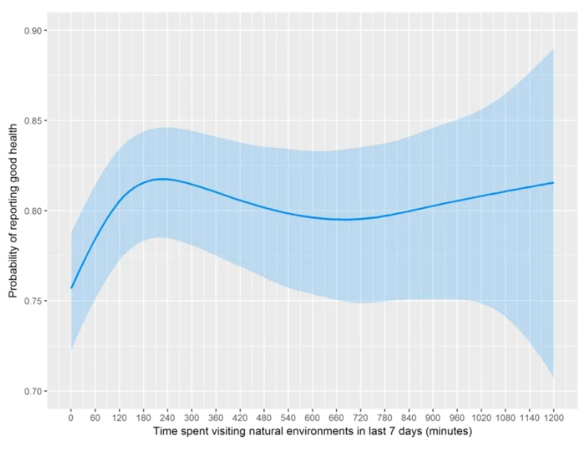

You can see from the figure below that the probability of reporting good health levels off after spending 120 minutes in nature, giving us the time ‘dose’.

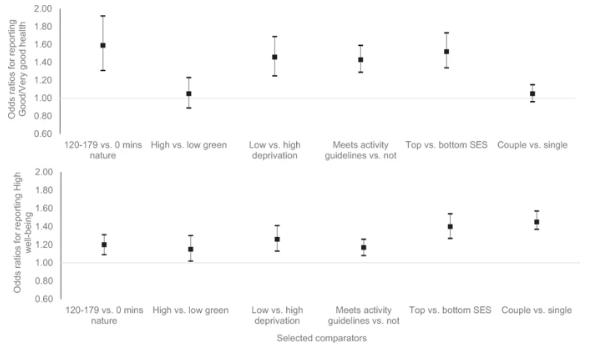

Again, this paper compared the effect of the nature dose to other commonly used socio-economic variables which are related to health and wellbeing. Getting a dose of nature had roughly the same odds of correlating with high self-reported health as being from a low versus high deprivation locality, meeting the physical activity guidelines or not, or being in a top social status job versus a bottom social status job (top panel of Figure 2). The likelihood of reporting good wellbeing was correlated most strongly with being in a couple and having a high social status job but getting a dose of nature was as good a predictor as was meeting activity guidelines or coming from an area of low deprivation (lower panel of Figure 2).

Again, this paper compared the effect of the nature dose to other commonly used socio-economic variables which are related to health and wellbeing. Getting a dose of nature had roughly the same odds of correlating with high self-reported health as being from a low versus high deprivation locality, meeting the physical activity guidelines or not, or being in a top social status job versus a bottom social status job (top panel of Figure 2). The likelihood of reporting good wellbeing was correlated most strongly with being in a couple and having a high social status job but getting a dose of nature was as good a predictor as was meeting activity guidelines or coming from an area of low deprivation (lower panel of Figure 2).

In summary, both Kardin et al 2015 and White et al 2019 indicate that interacting with nature is good for both self-reported health and wellbeing (for a 2019 review paper with consensus statements about the field (!) see here).

What about a nature experience improves psychological wellbeing?

Given the evidence that nature experiences can be beneficial, the question then becomes what factor moderates the wellbeing benefit? Speaking broadly, we can approach this from the two sides of the human-nature interaction: from the human side we can consider the person’s attitude towards nature, their orientation, and from the nature side we can consider the availability of nature to interact with, the opportunity. To explore which factor is more important, orientation or opportunity, a representative survey of the population of Brisbane, Australia, was undertaken. Respondents were asked whether they had visited a park in the last week and how close the park was to their home address, a measure of opportunity. Each respondent also filled out a Nature Relatedness survey, a measure of orientation (to see what your nature relatedness score is fill out this survey, I got 3.8). Park users had significantly higher nature relatedness scores compared to non-park users, and nature relatedness was a much better predictor of park visitation than how close someone lived to a park. Similarly, Colleony et al. 2020 conducted a study in Tel Aviv, Israel, which provides further empirical support that it is one’s attitude towards nature, more so than the opportunity to visit nature, that determines the wellbeing people gain from nature experiences. This is encouraging as it indicates that while we should be concerned about green space justice issues in cities, such as more deprived areas having lower green space, one of the best ways to encourage people to engage in nature experiences is to increase their relatedness to nature.

Now, I have some reservations about using the Nature relatedness index and another commonly used scale, the Connectedness to Nature Scale, as the factors to optimise if we are interested in boosting the wellbeing gained from nature experiences. The Nature Relatedness index includes items like ‘Humans have the right to use natural resources any way we want’ and ‘Animals birds and plants should have fewer rights than humans’, which indicates the index is measuring one’s philosophical and political views; essentially the degree to which one is an environmentalist. While an appreciation of natural beauty, ecological knowledge and enjoying a sense of wildness do correlate with environmentalism, which the Nature Relatedness index was designed to measure, it is not true that only environmentalists can appreciate natural beauty or enjoy a sense of wildness. (I don’t self-identify as an environmentalist, yet I have an extremely close connection to nature and only come out at 3.8 on the nature relatedness scale.) Indeed, a study in 2014 by Zhang et al. illustrated that that the real moderating factor between psychological wellbeing and nature experiences was the ability to perceive natural beauty.

It is clear to any ecologist that all greenspace is not all created equal, so while many papers have used the availability of nearby greenspace to measure ‘nature’, ecologists have attempted to determine whether the biodiversity of greenspace matters. An early and influential paper by Fuller et al. 2007 showed a relatively strong positive relationship between species richness of urban parks in the UK and various measures of psychological wellbeing that people got from using the parks. An experimental study in Switzerland tasked people with ranking assembled meadow-like arrays of potted plants in terms of their aesthetic beauty. Species richness and evenness were varied in each array, with individual species being assigned to an array at random to control for any species level effect. Participants responded to both the richness and evenness of an array, indicating that plant diversity in itself is attractive to humans. In a recent experimental study in the UK meadows of different richness and height were established in parks, with a clear aesthetic preference been shown for species rich meadows of medium height.

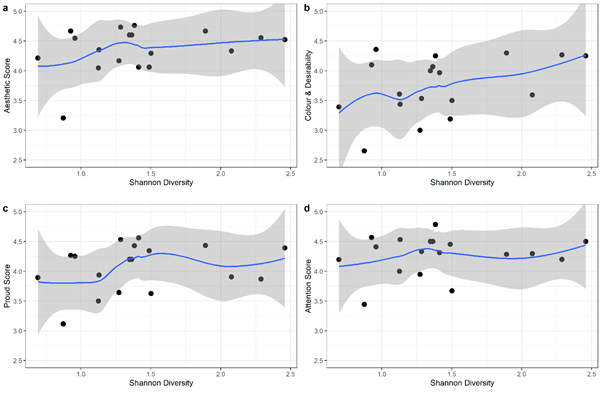

However, the UK study found no impact of perceived biodiversity on health or psychological wellbeing metrics, in contrast to the early Fuller paper. Indeed, some of my own work shows that while there are positive trends between floral diversity of urban meadows and various measures of psychological wellbeing (especially colour and desirability, see Figure 3b), there was no significant effect of floral diversity. Yet, figure 3 does indicate that park users in Dublin generally appreciate the meadows, regardless of floral diversity, a score above 3 indicating agreement that the meadows positively impact various measures of self-reported psychological wellbeing.

So, while all greenspace is not created equal, and there is experimental evidence that people prefer green spaces with higher diversity, the link between diversity and psychological wellbeing is more tenuous. Yet, while diversity per se has mixed evidence of impact, nature, taken as greenspace, does have more robust effects on psychological wellbeing. It is early, though, to draw conclusions. I don’t think enough of the studies are of sufficient quality, including my own, to really answer the question about species diversity effects of psychological wellbeing and the topic would benefit from closer collaboration between ecologists and psychologists. More generally, the field of positive human-nature interactions is crying out for a robust meta-analysis. A vote count, (a simple tallying of studies which found positive, negative or non-significant effects), was published as part of an issue on human nature interactions in Frontiers in Psychology, but vote counts are a poor way to quantitatively summarise a field. Fortunately, science isn’t a democracy.

Why would interacting with nature create wellbeing benefits?

If we are to believe that interacting with nature has wellbeing benefit, we need good explanations for why. E. O. Wilsons posits that humans are biophilic and ‘possess the urge to affiliate with other forms of life’. Due to our evolutionary history we are naturally orientated to be subconsciously attracted and have positive feeling for organisms and their natural surroundings. This biophilia hypothesis has since been used as the evolutionary scaffold on which to build two theories: Attention Restoration Theory (ART), which posits cognitive improvements through regaining a depleted psychological resource, (attention), by interacting with softly fascinating nature, and Stress Reduction Theory (SRT), which claims affective (emotional) benefits through interacting with unthreatening natural settings. The idea goes that ‘water, trees and foliage are all indicators of the habitats in which human survival is more likely’ and so ‘people will restore better [or have positive affect] in environments that have characteristics that were relevant for survival during early evolution’. To my mind these are quite poor explanations for why we should see any benefit of interacting with nature and are more just-so evolutionary stories (see here and here for good critiques of ART and SRT). There seems to have been stagnation in the search for the ultimate reason why we are seeing some of the benefits for interacting with nature, which is both disappointing and exciting.

My thought on this is that maybe we shouldn’t be looking for adaptive reasons. Richard Prum in the Evolution of Beauty, see here for review paper covering the core idea, argues that a species conception of beauty can initially start out picking some adaptive trait, such as a longer tail for gliding with, but as the preference for that trait and the trait itself co-evolve we get a Fisherian runaway process. The aesthetic preference and the benefit to having a long tail become uncorrelated. The species’ females’ aesthetic preference now doesn’t serve an adaptive function, it’s now arbitrary that the species prefers long – long tails compared to just long tails. In some populations of bower birds, the females like the colour white, while in others they like the colour blue. Neither colour is more difficult to find in the environments they live, it’s just that in one population the preference for blue fixated, while in another the preference for white fixated, arbitrary conceptions of beauty.

Maybe in humans, like the long-long tailed birds, beauty was initially an indicator of mate quality (symmetrical faces and golden ratios in body parts indicating good genes and health) and now we see beauty wherever there is symmetry, fractals or golden ratios. Or maybe a preference for symmetry, fractals and golden ratios arose from the need to identify objects when viewed from many different positions. Or maybe, like the bower birds, physical aspects of natural environments have become arbitrarily fixed as beautiful. It’s a fascinating topic and, while there are many proposals for the ultimate reasons why humans see beauty in many places, there doesn’t yet seem to be a conclusive answer. For a great overview see this Kurzegesagt video.

A possible future

We must remember that most of the studies I have talked about so far are correlational, not experimental. It could just be that healthier, happier people visit nature more often or choose to live where there is more green space, i.e. there could be hidden moderating factors that really drive these results that weren’t accounted and, even worse, reverse causality could be occurring. We need experiments to really get at that causality which is why I was very excited to hear a talk given at the 2019 British Ecological Society’s annual meeting. The study was led by Dr Agathe Colleony who experimentally manipulated aspects of human behaviour during a nature experience. The design asked participants to walk a set route through a park and assigned a participant to interact with nature predominantly using one sense. For example, a participant might be assigned touch, and they predominantly interact with nature through touch, whereas another participant might be assigned to sight. The result found that psychologically ‘close’ interactions with nature produced higher wellbeing reports. That is, smelling a flower, as opposed to viewing it, produced greater self-reported wellbeing. The paper is still in press, so I can’t comment on the robustness of the methods or analysis, but the result it intuitive enough: the immediacy of interactions created more meaningful nature experiences.

Agathe Colleony’s study also found that people who were allowed keep their phone for the walk through the park reported greater wellbeing than those who were asked not to have their phone on them. The mechanism suggested is what people felt safer when they had a mobile and so could immerse themselves more in the task of experiencing nature. Couple this with the widespread use of plant identification apps, such as PlantNet, and the increasing interest in Nature-based Interventions aimed to boost wellbeing, and it is likely that nature-therapy apps will be developed to train people in how to create meaningful nature experiences. The success of mediation apps like Headspace , Waking Up and 10% Happier demonstrate the market for apps that assist in developing a practice to boost wellbeing and gain deeper insights into the mind. A similar market could exist for apps that encourage people to have meaningful interactions with nature by providing ecological lessons, opening people to appreciate natural beauty, and mindful nature walks. Such apps need not only be beneficial to the wellbeing of individuals. If these apps can change one’s orientation to nature to enhance the meaningfulness of nature experiences, a co-benefit would be increasing people’s pro-environmental behaviours and attitudes.

So, while the science has a way to come to conclusively show how and why nature experiences are beneficial to wellbeing, there does seem to be a burgeoning consensus that nature, broadly conceived, has a positive impact on our psychology. Saying this to a group of ecologists is likely to elicit raised eyebrows at the obviousness of such statements, but in a world where more people live in cities than not, and where taking 10 minutes to just breathe is a global movement, maybe taking 10 minutes to smell the flowers, touch the bark of a tree, or listen to the birds sing will be the next big thing. Hopefully it will make everyone just a little bit less stressed, and a little bit more interested in the natural world.

Thanks Cian, I really enjoyed reading that, especially the parts about the Agathe Colleony’s work and about diversity and the evolution of beauty.

That White 2019 study (superficially at least) seems to suffer very badly from the classic causation or correllation problem (as you mention too). I think very likely that what is really happening is that most people don’t spend more than 2hrs outdoors in a week if they dont feel well. Or at least that that hypothesis can’t be told apart from the suggestion that spending more than 2hrs outdoors makes people feel well (using their dataset). The Kardin et al. study seems a lot less confounded. Thanks again for writing this, really very interesting stuff.