This is a mini series of two posts about finding positive things in negative results. Science is often a trial and error process and, depending on what you’re working with, errors can be fatal. As people don’t usually share their bad experiences or negative results beyond the circle of close colleagues and friends, I thought (and hope!) that sharing my point of view, as a PhD student might be useful.

If you’re about to do a PhD you will fail and if you’ve already successfully finished one, you have failed. At least a little bit… come on… are you sure? Not even a teeny tiny bit? By failure, I just mean scientific failure here, as if you ran an experiment and the result was… a fail, no results, do it again. There are millions of ways to fail, from errors in the experimental design to clumsiness but in this series of posts, I want to emphasize the consequences of failure more than its causes. I think that it is an important thing to learn and to embrace as a young future scientist, as much as journal rejection and other annoying and common silent academic failures.

During the two first years of my PhD, I went from the idea of quickly testing some assumptions as a starting point for a bigger question to some detailed and time consuming simulations on a detailed part of these assumptions. The time spent appeared to be completely useless scientifically because the analysis failed leading to false negative results and kept me away from going back to the bigger question. Or did it?

When wrong is right part 1

Since the summer of last year, I was working on an intensive computational project. I was running a kind of sensitivity analysis to see the effect of missing data on the phylogenies that have both living and fossil species (that’s called Total Evidence to link back to former posts, here and here). In brief I was simulating datasets with a known (right) result by removing data from it to see how the results were affected. Because of my wide ignorance at the start in coding, simulations and the method I was testing, the project took way longer than planned. And all that was of course ignoring Hofstadter’s law (‘it always takes longer than you think, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law’).

The expected result, as for any sensitivity-like analysis, was that as you reduce the amount of data, the harder it would be to get the right results. That wasn’t what I found at all. Instead, my simulations seemed to be suggesting that whatever the amount of data, you never get the right results. Suspicious, I tried to check my simulations and asked advice from competent and talented people that helped me finding caveats in my project. But still, after checking and testing everything over and over again, the simulation results appeared to be the same: the amount of data doesn’t matter, the method just don’t work.

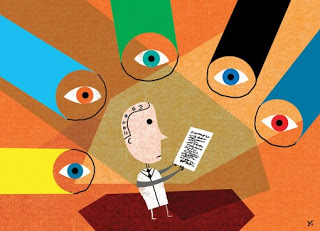

Even though these results were negative, they were intriguing and, if they were right, probably important because of the number of people willing to try the Total Evidence method over the last three years. From that perspective, I presented my results at the Evolution 2014 conference in Raleigh. There, I got even more comments from even more people but still, the results appeared to be right. Until one person that had a similar unexpected result suggested that should try an older version of some of the software I was using.

It appeared that person was right and all the weirdness in the results that I tried for months to fix, check and explain were caused by a bug in the latest update (don’t use MrBayes 3.2.2 for Total Evidence analysis, prefer the version 3.2.1).

After an obvious moment of relief, came an obvious negative feeling of having lost my time and how I should have given up instead of continuing to dig. But a posteriori, I’m actually glad of this misadventure and learned two really important lessons: (1) published software is not 100% reliable; always test their behaviour; (2) there is nothing more productive than sending your work to colleagues and experts for pre-reviewing. Even though, the bug appeared to be “trivial and easy to fix”, the amount of comments I had definitely helped improve both my understanding and my standards for this project.

Author: Thomas Guillerme, guillert[at]tcd.ie, @TGuillerme

Photo credit: wikimedia commons